Table of Contents

- What Do Astrophysicists Mean by Dark Matter?

- Observational Evidence for Dark Matter Across Scales

- Dark Matter or Modified Gravity? Competing Theories

- Leading Dark Matter Candidates and Particle Physics Models

- How Scientists Search for Dark Matter: Direct, Indirect, and Collider

- Mapping Dark Matter with Gravitational Lensing and Simulations

- Dark Matter’s Role in Galaxy Formation and Cosmic Structure

- Current and Upcoming Experiments and Surveys

- Common Misconceptions and How to Evaluate Claims

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Final Thoughts on Understanding Dark Matter Research

What Do Astrophysicists Mean by Dark Matter?

Dark matter is a form of matter that does not emit, absorb, or reflect light in any measurable way, yet it reveals itself through gravity. Astronomers infer its presence because stars, gas, and entire galaxies move as if there is far more mass present than we can see with telescopes. In contemporary cosmology, dark matter is thought to constitute most of the matter in the universe, with normal matter (the protons, neutrons, and electrons that make up stars and planets) making up only a minority of the cosmic mass budget.

When astrophysicists say “dark matter,” they refer to a physical substance that gravitates—clumps, forms halos around galaxies, and participates in the growth of structure—yet interacts weakly, if at all, with electromagnetic radiation. This is different from “dark energy,” which is a distinct component thought to drive the accelerated expansion of the universe. Conflating the two is a common mistake; dark matter behaves like matter, dark energy does not.

The dark matter framework arose from multiple, independent lines of evidence. Early hints appeared in the 1930s, when cluster galaxies were observed to move too quickly to be bound by visible mass alone. In the 1970s, precise measurements of spiral galaxy rotation curves showed that orbital speeds of stars remained high far beyond the visible disk, implying an extended, unseen mass distribution. Since then, gravitational lensing, the cosmic microwave background (CMB), galaxy clustering, and simulations have all converged on a consistent picture in which dark matter is a cornerstone of cosmic structure. We will explore these observations in detail in Observational Evidence for Dark Matter Across Scales.

Artist: ESA and the Planck Collaboration

In particle physics language, the simplest possibility is that dark matter is made of new particles beyond the known Standard Model, such as weakly interacting massive particles (WIMPs) or axions. But multiple candidate ideas exist, from ultralight “fuzzy” dark matter to self-interacting dark matter. We will review the leading proposals in Leading Dark Matter Candidates and Particle Physics Models and discuss how to look for them in How Scientists Search for Dark Matter: Direct, Indirect, and Collider.

In short, dark matter is not a placeholder for ignorance. Rather, it is a testable, quantitative hypothesis that ties together a wide range of precise measurements about the universe. As new datasets pour in from advanced telescopes and underground detectors, the field is rapidly honing in on what dark matter is—and what it is not.

Observational Evidence for Dark Matter Across Scales

Evidence for dark matter comes from phenomena spanning from the sizes of dwarf galaxies to the overall geometry of the universe. The following lines of evidence are mutually reinforcing.

Galaxy Rotation Curves

In a spiral galaxy, stars orbit the galactic center. If most of the mass were concentrated where the light is—primarily in the bright central bulge and disk—then orbital speeds should drop with radius, much as planets slow down the farther they are from the Sun. In Newtonian terms:

v(r) ≈ √(G · M(r) / r)

where v(r) is the circular velocity at radius r, and M(r) is the mass enclosed within that radius. Observations show that rotation curves remain roughly flat well beyond the visible edge of many spiral galaxies. This flatness implies that M(r) continues to grow with r, requiring a massive, extended “halo” of unseen matter.

Galaxy Clusters and the “Missing Mass”

Galaxy clusters are the most massive gravitationally bound structures in the universe. When astronomers measure the speeds of galaxies within a cluster, the hot X-ray-emitting gas bound in the cluster, and the way the cluster bends light from background galaxies (gravitational lensing), they consistently infer far more mass than is visible in stars and gas. The discrepancy is too large to be explained by normal matter that is simply dim or difficult to detect.

Gravitational Lensing Mass Maps

Einstein’s general relativity predicts that mass curves spacetime, bending the paths of light. When a massive foreground object lies along the line of sight to a background galaxy, we can measure the small distortions in the background galaxy’s apparent shape. This effect, called weak gravitational lensing, allows astronomers to map the total distribution of mass—dark or luminous—without assumptions about how matter emits light.

Weak lensing surveys of many patches of sky have created two-dimensional “mass maps” showing dark matter filaments connecting galaxies and clusters. These maps align with where cosmological simulations of dark matter predict gravity should pull matter over billions of years. We return to these techniques in Mapping Dark Matter with Gravitational Lensing and Simulations.

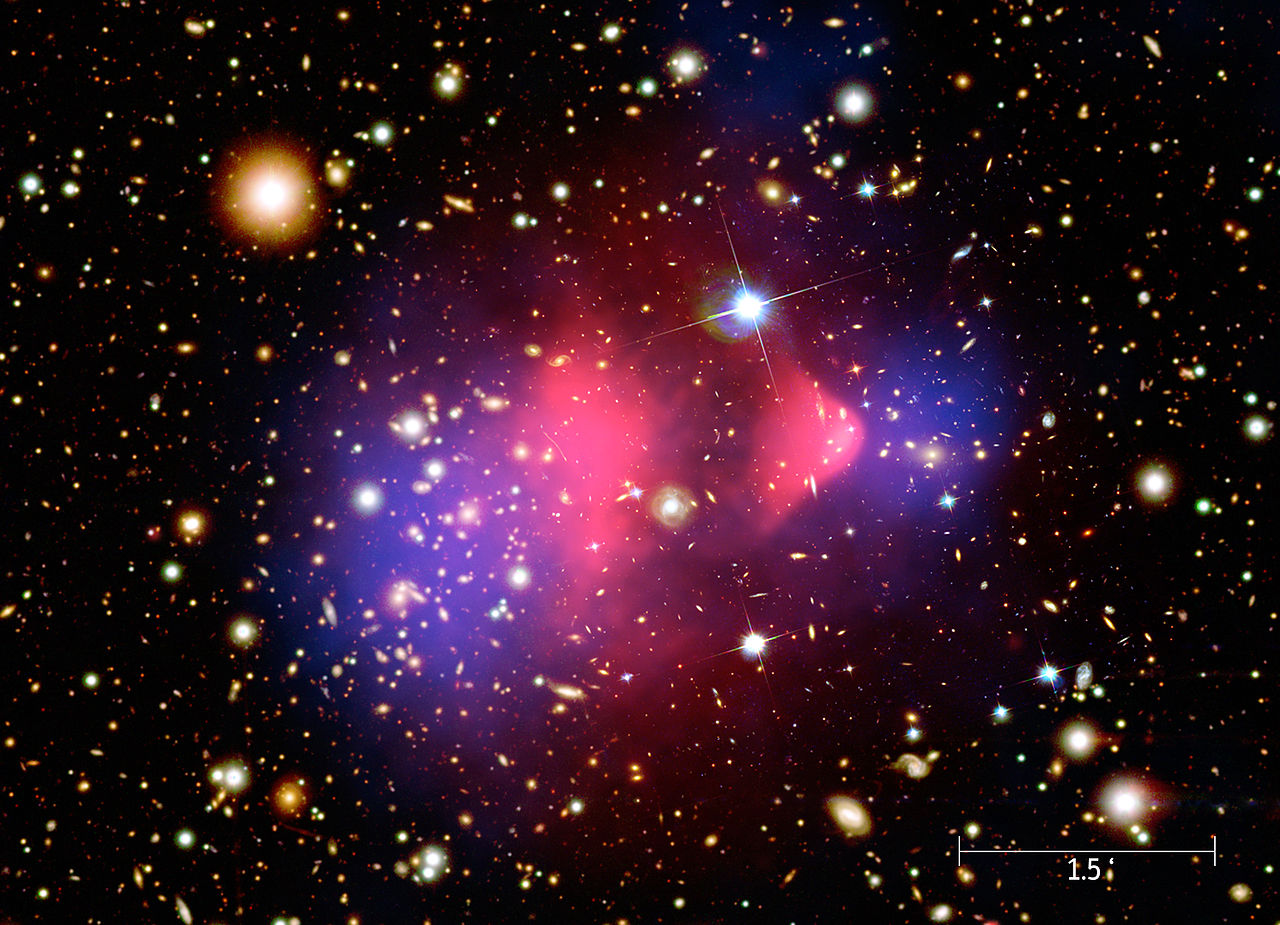

The Bullet Cluster and Colliding Systems

In some cluster collisions, like the so-called Bullet Cluster, the hot gas (which contains much of the baryonic, or normal, mass) is slowed by friction, while the gravitational lensing signal peaks ahead of the gas, near the galaxies. This offset suggests the bulk of the mass passed through the collision with minimal drag—consistent with a collisionless dark matter component. While any single system must be interpreted carefully, multiple merging clusters show similar behavior, providing strong constraints on how strongly dark matter can interact with itself.

Artist: NASA/CXC/M. Weiss

Cosmic Microwave Background (CMB) and the Early Universe

The CMB is the afterglow of the Big Bang, imprinted when the universe was just 380,000 years old. Its tiny temperature fluctuations tell us about the composition and geometry of the early universe. Analyses of these patterns reveal that normal matter alone cannot account for the observed peaks and troughs in the CMB power spectrum. A pressureless matter component—dark matter—fits the data and, together with dark energy, explains the overall spatial geometry and growth of structure. Independent constraints from Big Bang nucleosynthesis also limit how much normal (baryonic) matter could have been present, supporting the need for a non-baryonic dark component.

Large-Scale Structure and Baryon Acoustic Oscillations

Galaxies are not uniformly spread out; they trace a cosmic web of clusters, filaments, and voids. Surveys of millions of galaxies reveal patterns consistent with the gravitational collapse of initial fluctuations dominated by cold (slow-moving) dark matter. The imprint of baryon acoustic oscillations—a relic ripple from sound waves in the primordial plasma—provides a standard ruler for cosmic distances and reinforces the composition inferred from the CMB, including the presence of dark matter.

Dwarf Galaxies and Satellite Systems

Small, faint galaxies orbiting larger ones often exhibit mass-to-light ratios much higher than those of big spirals. Their internal motions suggest they are strongly dark-matter dominated. Such dwarfs also serve as clean laboratories to search for dark matter’s particle signatures, as discussed in How Scientists Search for Dark Matter.

The convergence of these lines of evidence—from galaxy scales to the early universe—makes a compelling case that most of the universe’s matter is dark and non-baryonic. That does not end the story: alternate gravitational theories aim to explain some observations without invoking new matter. We discuss their merits and limits in Dark Matter or Modified Gravity?.

Dark Matter or Modified Gravity? Competing Theories

Whenever an invisible ingredient is proposed, a healthy scientific response is to ask whether we could instead be misapplying the laws of physics. Modified gravity theories attempt to explain mass discrepancies by changing how gravity works on galactic and larger scales, rather than adding unseen matter.

Modified Newtonian Dynamics (MOND)

One of the best-known ideas is MOND, which posits that Newton’s second law or the law of gravity changes at very low accelerations. MOND can reproduce the flat rotation curves of spiral galaxies and relations like the baryonic Tully–Fisher relation surprisingly well with a small number of parameters. This success suggests any full theory of galaxies must match these empirical regularities.

Artist: ScienceDawns

Relativistic Extensions and Cosmology

Because MOND is not a relativistic theory on its own, various extensions have been proposed to be consistent with general relativity. These frameworks aim to address gravitational lensing and cosmology. However, matching the full suite of evidence—including the CMB and cluster dynamics—has proven challenging. Some modified gravity models can handle certain datasets, but rarely all without reintroducing a dark component.

Why Dark Matter Remains the Leading Paradigm

The leading reason dark matter remains favored is that it offers a single, quantitatively successful framework that accounts for diverse observations: galaxy rotation curves, lensing, cluster dynamics, the CMB, and the formation of large-scale structure. Modified gravity can emulate some of these phenomena, particularly on galaxy scales, but often struggles on clusters and cosmological scales or ends up effectively adding unseen mass in another guise. That said, the dialogue between these approaches is valuable, sharpening predictions and highlighting where data are most discriminating.

Ultimately, nature decides. Clear, decisive particle detections or astrophysical signals consistent across multiple channels would tip the scales. Until then, the best approach is to compare models against high-quality data, a theme we return to in Current and Upcoming Experiments and Surveys and Mapping Dark Matter with Gravitational Lensing and Simulations.

Leading Dark Matter Candidates and Particle Physics Models

What could dark matter be made of? We do not yet know, but several well-motivated candidates have emerged from particle physics and cosmology. Each has distinct properties and detection prospects.

Weakly Interacting Massive Particles (WIMPs)

WIMPs are hypothetical particles with masses roughly between a few GeV and a few TeV that interact via the weak nuclear force (or something similar). A key appeal is the “WIMP miracle”: a particle with weak-scale interactions naturally freezes out of the hot early universe with a relic abundance close to what we infer for dark matter today. This coincidence motivated decades of experimental searches. Many concrete WIMP models are now highly constrained, but an enormous parameter space remains, including non-minimal couplings and extended dark sectors.

Axions and Axion-Like Particles (ALPs)

Axions were originally proposed to solve the strong CP problem in quantum chromodynamics. If light and stable, they can be produced non-thermally in the early universe and constitute cold dark matter. Axions couple very weakly to photons, which allows for resonant conversion in magnetic fields. A broader family of axion-like particles (ALPs) appears in many extensions of the Standard Model, prompting a diverse set of experimental strategies.

Sterile Neutrinos

Sterile neutrinos are hypothetical neutrinos that do not interact via the weak force. If their masses are in the keV range, they could act as “warm” dark matter, with free-streaming lengths larger than cold dark matter. This would slightly suppress structure formation on small scales, potentially addressing certain galaxy-scale tensions. X-ray observations constrain their properties, as decays could produce characteristic X-ray lines.

Primordial Black Holes (PBHs)

Formed in the early universe from over-dense regions, primordial black holes could in principle make up part of the dark matter. However, a range of observations—microlensing, gravitational wave merger rates, and dynamical effects—place strong constraints on how much of the dark matter they could represent across different mass ranges. While some mass windows remain less tightly bounded, PBHs are unlikely to account for all dark matter.

Self-Interacting Dark Matter (SIDM)

In the standard cold dark matter picture, dark matter is effectively collisionless. SIDM adds the possibility that dark matter particles scatter off each other with a small cross section. Such interactions can redistribute energy within halos and potentially ease tensions like the cusp–core discrepancy in dwarf galaxies. Observations of cluster collisions and halo shapes constrain how strong such self-interactions can be.

Ultralight or “Fuzzy” Dark Matter

This model posits extremely light bosons with masses around 10^-22 eV. Quantum effects on kiloparsec scales can behave like a pressure that smooths small-scale structure, producing cored halo profiles. This class of models is under active investigation through galactic dynamics and the Lyman-alpha forest, which track small-scale structure at high redshift.

Multi-Component and Hidden-Sector Models

Nature may be more complex than a single particle species. Hidden sectors with dark forces, dark photons, or multiple interacting components can produce a rich landscape of signals across astrophysical and laboratory experiments. These possibilities expand the search space and motivate complementary detection strategies, as discussed in How Scientists Search for Dark Matter.

How Scientists Search for Dark Matter: Direct, Indirect, and Collider

Turning the concept of dark matter into a concrete discovery requires observing a non-gravitational imprint. Three broad strategies—direct detection, indirect detection, and collider searches—offer complementary paths. Axion-specific techniques add a fourth pillar. As of the time of writing, no claim of particle dark matter detection has been universally confirmed. Limits, however, are rapidly improving.

Direct Detection: Waiting for a Particle to Hit

Direct detection experiments aim to see dark matter particles scattering off nuclei or electrons in ultrapure detectors located deep underground (to shield against cosmic rays). The most sensitive experiments use large volumes of liquid xenon or argon, cryogenic semiconductors, or scintillating crystals. They measure tiny energy deposits from hypothetical interactions.

- Dual-phase xenon detectors (e.g., modern large-scale instruments) search for nuclear recoils and distinguish them from background using simultaneous light and charge signals.

- Cryogenic phonon and ionization detectors push sensitivity to low-mass dark matter candidates by precisely measuring heat and charge.

- Novel technologies (e.g., superfluid helium, Dirac materials) aim to probe very light dark matter that transfers minimal energy.

As sensitivities increase, experiments approach the “neutrino floor,” where backgrounds from solar, atmospheric, and supernova neutrinos begin to mimic dark matter signals. Surpassing this threshold will require directional detection or new discrimination techniques. Nevertheless, a clear signal above known backgrounds—ideally with an annual modulation or directionality signature—would be compelling. We revisit the outlook in Current and Upcoming Experiments and Surveys.

Indirect Detection: Looking for the Aftermath

If dark matter particles annihilate or decay, they could produce standard particles such as gamma rays, electrons/positrons, antiprotons, or neutrinos. Indirect detection telescopes analyze the skies for excesses with the right energies and spatial distributions:

- Gamma-ray telescopes target regions with high dark matter density like the Galactic center and dwarf spheroidal galaxies.

- Cosmic-ray experiments measure antimatter components for anomalies; interpreting these data requires careful modeling of astrophysical backgrounds.

- Neutrino observatories search for signals emanating from the Sun or Earth, where dark matter could accumulate and annihilate.

Interpreting any signal demands caution, as astrophysical sources can mimic or mask potential dark matter signatures. Confirmation ideally requires consistent signals across multiple targets and messengers, as well as correlation with parameters probed by direct and collider searches.

Collider Searches: Making Dark Matter in the Lab

High-energy colliders can produce new particles if they are within reach of the available energy. Dark matter particles would escape the detector unseen, leading to events with “missing transverse energy.” Searches look for such missing energy in association with other particles (a jet, photon, or weak boson). While collider signals are not proof that a particle is cosmological dark matter, they can reveal new physics and guide model building in tandem with candidate theories. Absence of signals at colliders places important constraints on interaction strengths and masses.

Axion Detection: Resonance and Precision

Axion and ALP searches often exploit their tiny coupling to photons. Microwave cavity experiments place a resonant cavity in a strong magnetic field to stimulate axion-to-photon conversion; by tuning the cavity frequency, they scan axion masses. Other approaches include broadband searches using quantum sensors, dielectric haloscopes, nuclear magnetic resonance techniques for axion–nucleon couplings, and helioscopes that search for axions streaming from the Sun. Progress is steady, driven by advances in cryogenics, quantum-limited amplification, and magnet technology.

Mapping Dark Matter with Gravitational Lensing and Simulations

Even without identifying the particle, we can map where dark matter lies and how it evolves. Two powerful techniques—gravitational lensing and cosmological simulations—reveal the dark scaffolding of the cosmos.

Weak Lensing and Cosmic Shear

Weak lensing measures minute, coherent distortions in the shapes of distant galaxies caused by intervening mass. By averaging over many galaxies, astronomers extract a “cosmic shear” signal that traces the projected matter distribution. From these measurements, they derive mass maps and statistical descriptors (two-point functions, higher-order moments) that constrain the amplitude of matter clustering and the growth of structure over cosmic time.

Multiple surveys have independently measured cosmic shear and produced dark matter maps that align with theoretical expectations from the cold dark matter model. Systematic uncertainties—like how to calibrate galaxy shapes or measure precise distances—are carefully modeled. Ongoing and upcoming surveys aim to tighten these measurements, improving constraints on both dark matter and dark energy.

Strong Lensing: Arcs, Einstein Rings, and Substructure

Artist: ESA/Hubble & NASA; derivative work: Bulwersator

In strong lensing, the alignment between lens and source is so precise that we observe dramatic arcs or even full Einstein rings. By modeling these features, astronomers can precisely infer the lens’s mass distribution, including small-scale clumps (subhalos) that reveal the granularity of dark matter. Counting and characterizing substructure tests predictions of the cold dark matter paradigm versus alternatives like warm or fuzzy dark matter, which would smooth away the smallest clumps.

Simulations: From Initial Conditions to Galaxies

Numerical simulations start with initial conditions informed by the CMB and evolve them forward under gravity (and, in hydrodynamic simulations, gas physics and stellar feedback). Pure dark matter simulations produce a cosmic web resembling observations, with halos hosting galaxies at the nodes of filaments. When baryonic physics is included—cooling, star formation, supernova and black hole feedback—simulations can reproduce observed galaxy populations more accurately.

Simulations are essential for interpreting observations, designing surveys, and testing dark matter models. They quantify how different dark matter properties (e.g., self-interactions or particle mass) alter halo density profiles, subhalo abundances, and lensing signals. This closes the loop between theory and measurement, turning astrophysical data into constraints on microscopic physics.

Mass Calibration and Cross-Checks

Lensing provides a direct mass probe, while galaxy dynamics, satellite counts, and X-ray observations offer complementary views. Combining these datasets refines mass calibration, reduces systematics, and tests the consistency of the dark matter picture. Statistical cross-correlations—for example, between lensing maps and galaxy surveys—boost sensitivity and mitigate biases.

Dark Matter’s Role in Galaxy Formation and Cosmic Structure

Dark matter sets the stage on which galaxies form. Its gravitational pull assembles matter into halos, within which gas can cool and condense into stars. Understanding this scaffolding is crucial for explaining how galaxies like the Milky Way came to be.

Hierarchical Growth: From Small to Large

In the cold dark matter paradigm, small structures collapse first and merge over time to form larger systems. This hierarchical growth produces a rich substructure: satellite galaxies orbit host halos, and clusters contain sub-halos and filaments. Observations of galaxy clustering and the abundance of halos across mass scales broadly match this picture.

Small-Scale Challenges and Feedback

While large-scale predictions are highly successful, galaxy-scale puzzles have sparked lively debate:

- Cusp–core problem: Simulations of collisionless cold dark matter produce “cuspy” inner density profiles, but some dwarf galaxies appear to have flatter “cores.” Energetic feedback from supernovae and active galactic nuclei can redistribute matter and flatten cusps, potentially resolving this tension without modifying dark matter.

- Missing satellites problem: Simulations predict many more small subhalos than the number of observed dwarf satellite galaxies. However, many subhalos may be too small to form stars efficiently. Improved surveys continue to find faint satellites, narrowing the gap. Reionization and feedback further suppress star formation in the smallest halos.

- Too-big-to-fail problem: The most massive predicted subhalos in some simulations seem too dense to host the brightest observed satellites. Baryonic physics that alters halo structure and improved observational completeness both help reconcile this issue.

Alternative dark matter models, such as warm dark matter or self-interacting dark matter, offer other ways to address these small-scale tensions. Disentangling astrophysical feedback from particle-physics effects is an active area where lensing, stellar dynamics, and new surveys play pivotal roles.

Galaxy–Halo Connection

The relationship between a galaxy’s properties and its dark matter halo—called the galaxy–halo connection—links observations to theory. Abundance matching and halo occupation distribution models map galaxy luminosities or stellar masses to halo masses, enabling predictions of clustering and satellite statistics. This framework is powerful for testing cosmology and constraining dark matter’s role in shaping galaxies.

Baryons Matter Too

Even in a dark matter–dominated universe, gas dynamics, star formation, and black hole activity play decisive roles. Baryonic effects can alter halo density profiles, expel gas from shallow potential wells, and heat or cool the interstellar medium, all of which feed back into how galaxies assemble. Therefore, comparing observations to dark matter predictions always requires accounting for baryonic physics—preferably using simulations and semi-analytic models that capture the essential processes.

Current and Upcoming Experiments and Surveys

The search for dark matter is a coordinated, global effort, spanning underground laboratories, particle colliders, high-altitude balloons, and space-based observatories. These projects provide complementary constraints and, potentially, discovery opportunities.

Direct Detection Experiments

Large noble-liquid time projection chambers and cryogenic detectors currently set leading limits on WIMP—nucleon scattering cross sections over a wide mass range. Successive generations scale up target mass, reduce backgrounds, and improve calibration. For sub-GeV dark matter, novel approaches such as superconducting sensors, crystal targets, and superfluid helium explore previously inaccessible parameter space.

A persistent theme is pushing below the irreducible background from coherent neutrino–nucleus scattering—the “neutrino floor.” Directional detection concepts aim to reconstruct the recoil direction to distinguish dark matter from solar neutrino backgrounds, which have known arrival directions.

Axion and ALP Searches

Microwave cavity experiments have achieved landmark sensitivity in a growing set of mass ranges, with quantum-limited amplifiers and strong magnetic fields enabling resonant conversion searches. Parallel efforts—dielectric haloscopes, broadband magnet-based searches, and precision spin-precession techniques—extend coverage to different masses and couplings. Solar axion searches (helioscopes) and light-shining-through-wall experiments explore complementary couplings.

Indirect Detection Facilities

Space-based gamma-ray observatories continue to survey the sky for dark matter–related excesses, while ground-based Cherenkov telescopes probe higher energies from dwarf galaxies and the Galactic center. Cosmic-ray spectrometers monitor antimatter components for anomalies that could hint at annihilation or decay. Neutrino observatories watch the Sun and Earth for annihilation products of captured dark matter.

Interpreting any excess requires careful modeling of astrophysical sources—pulsars, supernova remnants, and diffuse backgrounds—so collaboration between particle physicists and astronomers is essential.

Cosmological and Lensing Surveys

Wide-field imaging programs map billions of galaxies to measure weak lensing and galaxy clustering. These datasets inform the growth of structure, the amplitude of matter fluctuations, and the small-scale distribution of mass. Spectroscopic surveys measure redshifts for massive samples, charting baryon acoustic oscillations and redshift-space distortions that further constrain cosmological parameters.

Artist: CTIO/NOIRLab/DOE/NSF/AURA Image Processing: T.A. Rector (University of Alaska Anchorage/NSF NOIRLab) & M. Zamani (NSF NOIRLab)

Synergies are powerful: combining lensing with galaxy clustering and CMB lensing refines mass calibration and tests the consistency of the cosmic growth history with theoretical expectations. This is where mass mapping and galaxy–halo modeling meet precision cosmology.

Collider Programs

High-energy collider experiments continue to search for new physics beyond the Standard Model, including dark matter candidates and mediators. Analyses focus on missing-energy signatures, heavy resonance searches, and deviations in precision measurements. Results guide model building and help interpret any signals that might appear in astrophysical or direct-detection experiments.

Coordinated Data and Theory

The most robust conclusions arise when different approaches agree. For example, a gamma-ray excess consistent with annihilating dark matter would gain credibility if a corresponding direct-detection signal appeared at the expected scattering rate and a collider revealed a compatible mediator. Conversely, non-detections across channels carve out large regions of parameter space, informing where to search next and how to optimize instrument design.

Common Misconceptions and How to Evaluate Claims

Because dark matter is invisible and complex, it invites misunderstandings. Here are some clarifications that can help interpret headlines and evaluate new claims critically.

- “Dark matter is just a mathematical fudge factor.” In fact, it makes quantitative, testable predictions that successfully describe diverse data. Its presence is inferred from multiple, independent measurements, not one adjustable parameter.

- “Dark matter is the same as dark energy.” They are different. Dark matter behaves like matter, clustering under gravity; dark energy drives the universe’s accelerated expansion and does not clump in the same way.

- “Dark matter must be black holes.” While black holes contribute to the mass budget, a variety of observations limit the fraction of dark matter that can be made of primordial black holes over most mass ranges.

- “We know nothing about dark matter.” We know a great deal about its gravitational effects, spatial distribution, and impact on structure formation. We also have strong limits on many interaction strengths and masses for various candidates.

- “Any gamma-ray or cosmic-ray excess is dark matter.” Astrophysical sources can produce similar signals. A robust claim requires consistency across multiple targets and messengers, as well as agreement with other constraints.

- “No detection means dark matter is wrong.” Non-detections constrain models and guide new strategies. The parameter space is vast, and many plausible candidates remain to be tested.

When evaluating a new result, consider these questions:

- Is the signal statistically significant and reproducible?

- Are systematic uncertainties understood and convincingly bounded?

- Does the result align with other datasets (e.g., direct, collider, lensing)?

- Are alternative astrophysical explanations accounted for?

- Does the analysis clearly state model assumptions and priors?

Frequently Asked Questions

Is it possible that ordinary matter we cannot see accounts for the mass discrepancy?

Observations indicate that normal (baryonic) matter cannot make up the missing mass. Big Bang nucleosynthesis and the CMB tightly constrain the amount of baryons in the universe, and it falls well short of the total gravitational mass inferred from galaxy and cluster dynamics. While there is certainly dim and diffuse baryonic material (like hot gas and faint stars), these components are not abundant enough to explain the observed discrepancies. The remaining mass must be non-baryonic dark matter or a modification to gravity’s behavior. As outlined in Observational Evidence for Dark Matter Across Scales, multiple datasets independently require a non-luminous mass component.

How will we know dark matter has been discovered?

A convincing discovery would rest on converging evidence from different methods. For example, a statistically robust signal in a direct detection experiment—ideally with characteristics like annual modulation or directionality—would be strengthened if an indirect signal appeared with compatible particle properties and a collider observed related new particles or mediators. Consistency with lensing and cosmological data would further cement the case. The field aims for redundancy, because independent confirmation is the gold standard in physics.

Final Thoughts on Understanding Dark Matter Research

Dark matter is both a practical tool and a profound mystery. Practically, it lets astronomers model galaxy rotation, map mass in clusters, and predict the growth of structure with impressive accuracy. As a mystery, it challenges particle physics to extend beyond the Standard Model and beckons new technologies at the frontiers of sensitivity.

Artist: Daag

Across this article, we followed the evidence from galaxy dynamics and lensing to the cosmic web, examined rival ideas, surveyed candidate particles, and outlined how detectors and telescopes are working in concert to catch dark matter in the act. The scientific method is our compass: design multiple, independent tests; check for consistency; and let data, not preference, decide. Whether discovery comes from a faint nuclear recoil in an underground lab, a narrow spectral line in a microwave cavity, or a subtle pattern in a lensing map, the payoff will be a deeper, more unified picture of the universe.

If this overview sparked your curiosity, explore related topics in cosmology, particle physics, and galaxy evolution, and keep an eye on results from upcoming surveys and detectors. For more articles like this delivered to your inbox—including deep dives into gravitational lensing, galaxy formation, and emerging detection technologies—subscribe to our newsletter and join the conversation as the next chapter of dark matter science unfolds.