Table of Contents

- What Are Neutron Star Mergers and Kilonovae?

- The Extreme Physics Inside Neutron Stars

- From Inspiral to Afterglow: The Timeline of a Kilonova

- Cosmic Alchemy: r-Process Heavy Elements from Mergers

- Breakthrough Observations: GW170817, AT2017gfo, and Beyond

- How Kilonova Light Curves Reveal Ejecta Mass and Composition

- The Future of Multi-Messenger Astronomy

- How Amateurs and Citizen Scientists Can Follow Kilonovae

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Final Thoughts on Understanding Neutron Star Mergers

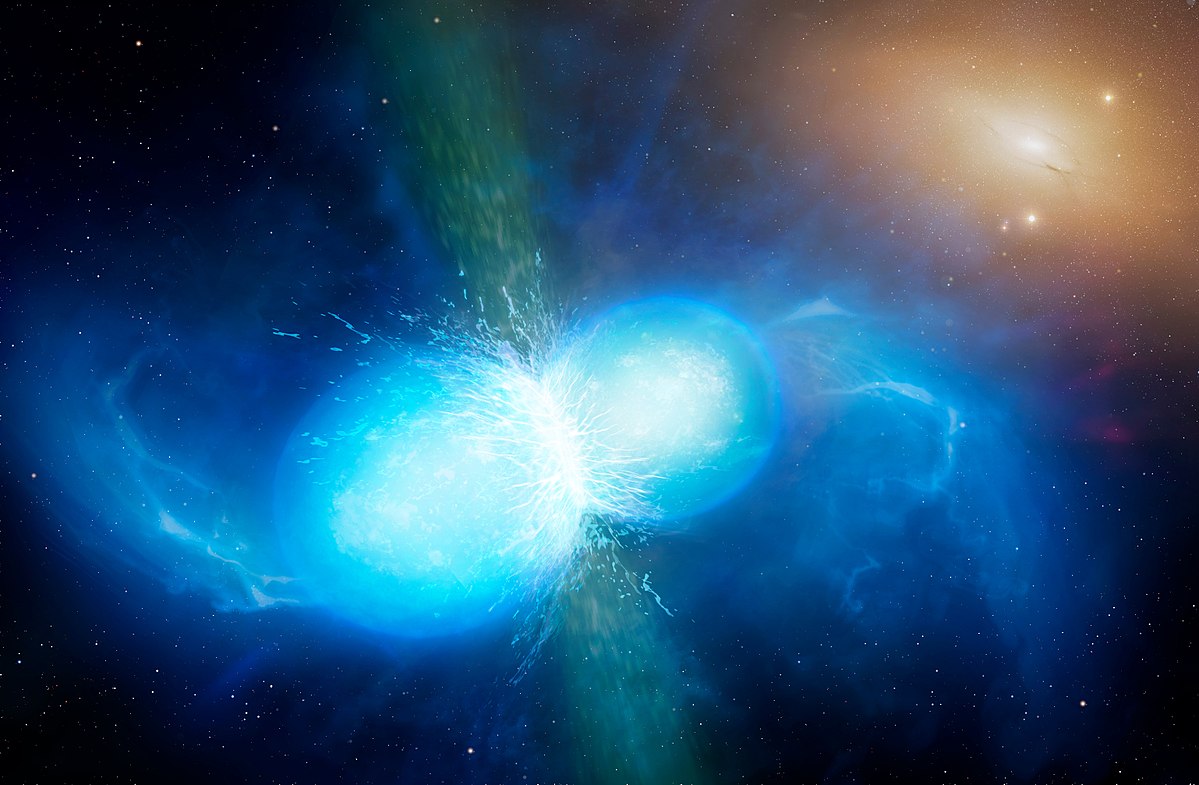

What Are Neutron Star Mergers and Kilonovae?

Neutron star mergers occur when two ultra-dense stellar remnants orbit one another and gradually spiral together due to the emission of gravitational waves. These stars are the collapsed cores of massive stars that ended their lives as supernovae. Each neutron star contains a mass comparable to the Sun compressed into a sphere roughly the size of a city, making them among the densest forms of matter in the universe outside black holes. When a pair finally collide, the event releases a torrent of energy across the electromagnetic spectrum and in gravitational waves, and it can synthesize new heavy elements through rapid neutron capture. The optical and infrared transient produced is called a kilonova.

Attribution: University of Warwick/Mark Garlick

The term nullkilonovanull reflects that these transients are typically about 1,000 times brighter than a classical nova yet generally dimmer and shorter-lived than supernovae. Kilonovae fade over days to weeks and shift in color from blue to red as the ejecta expand and cool. They are central to the cosmic production of heavy elements such as gold, platinum, and uranium via the r-process (rapid neutron capture).

For decades, astrophysicists predicted that neutron star binaries would be powerful sources of gravitational waves. The first direct confirmation arrived with the landmark detection of a neutron star merger by ground-based interferometers in 2017. The signal was accompanied by an electromagnetic counterpart observed across gamma-ray, optical, infrared, X-ray, and radio wavelengths, inaugurating the era of multi-messenger astronomy for compact object mergers. This breakthrough provided a single, coherent narrative linking compact object dynamics, relativistic jets, nucleosynthesis, and radiative transfer with unprecedented clarity.

Understanding neutron star mergers requires integrating diverse physics: general relativity, nuclear physics of dense matter, radiation transport in heavy-element-rich ejecta, plasma physics of relativistic jets, and the statistics of rare cosmic events. In this article, we explore the physics and observations behind kilonovae, the role of mergers in creating the periodic tablenulls heaviest elements, how astronomers read the light to infer composition, and what future facilities may reveal.

The Extreme Physics Inside Neutron Stars

To appreciate the drama of a neutron star merger, we need to understand what neutron stars are made of and how their interiors respond to extreme pressures. Neutron stars are composed primarily of neutrons with a small fraction of protons, electrons, and possibly muons. The physics of their interiors is governed by the equation of state (EoS) of ultra-dense matter, which describes how pressure relates to density. The EoS determines a neutron starnulls radius for a given mass, how easily it deforms in a gravitational field (its tidal deformability), and how it behaves in the final moments of a merger.

Key, robust facts about neutron stars:

- Masses typically cluster around 1null solar masses, with some measured near or above two solar masses.

- Radii are on the order of 10null14 km, constrained by X-ray timing and spectroscopic observations as well as gravitational-wave inferences.

- Central densities reach several times nuclear saturation density, where exotic states of matter may occur.

- Magnetic fields can be immense, with surface fields up to 1012null15 gauss in magnetars.

During the late inspiral of a neutron star binary, each star experiences tidal forces from its partner. These tides affect the shape of the stars and subtly alter the gravitational-wave signal. The amplitude and phase evolution carry information about the tidal deformability parameter (often denoted nullLambdanull). Observations have already begun to constrain Lambda, thereby narrowing the range of viable equations of state. A softer EoS implies smaller, more compact stars with lower tidal deformabilities; a stiffer EoS allows larger radii and higher deformabilities.

Another crucial property is whether the merger promptly collapses to a black hole or forms a hypermassive neutron star that survives transiently. This outcome depends on the total mass of the binary, the mass ratio, the spin, and the EoS. The remnantnulls fate has strong consequences for the electromagnetic emission and for the amount and composition of the ejected material.

The solid crust of a neutron star, a lattice of nuclei embedded in a sea of degenerate electrons, can host nullnuclear pastanull phases where nuclei arrange in elongated or planar structures due to competing nuclear and Coulomb forces. While these details unfold at microscopic scales, their macroscopic effects include crustal rigidity and potential impacts on starquakes and pulsar glitches. Although such crustal physics plays a smaller role in the merger itself than the bulk EoS, it exemplifies how neutron stars sit at the intersection of nuclear physics and astrophysics.

Ultimately, the EoS shapes the early post-merger dynamics: how much material is squeezed out dynamically, what fraction is unbound by shock heating or tidal torques, and how much mass remains in an accretion disk around the remnant. These quantities determine the kilonovanulls brightness and color and influence whether a relativistic jet can successfully punch through surrounding material to power a gamma-ray burst.

From Inspiral to Afterglow: The Timeline of a Kilonova

Neutron star mergers unfold across multiple channels of radiation, each peaking on its own timescale. The standard timeline ties together gravitational waves, gamma rays, optical/IR kilonova emission, and afterglow in X-ray and radio. Here is a simplified chronology from first principles and observations:

Attribution: International Gemini Observatory/NOIRLab/NSF/AURA/Double Dome Films

- Late Inspiral (minutes to seconds before merger): The binarynulls orbital frequency increases, producing a rising nullchirpnull in gravitational waves detected by kilometer-scale interferometers. The waveform encodes the component masses and tidal deformabilities.

- Merger (milliseconds): As the stars collide, some material is ejected dynamically. Depending on the compactness and mass ratio, the remnant may be a hypermassive neutron star supported temporarily by differential rotation and thermal pressure, or it may undergo prompt collapse to a black hole. Shock heating and tidal tails eject neutron-rich matter at sub-relativistic speeds (a few tenths of the speed of light).

- Short Gamma-Ray Burst (seconds): A relativistic jet can be launched from the remnantnulls central engine (a black hole or a massive neutron star plus an accretion disk). If the jet successfully breaks out and the observernulls line of sight is not too far off axis, gamma rays are detected as a short GRB lasting less than two seconds. Depending on geometry, the gamma-ray signal may be weak or even undetected despite a successful jet.

- Early Kilonova Emission (hours to ~1 day): Ejecta heated by radioactive decay produce thermal optical/UV light. If there is a component of ejecta with relatively low abundance of lanthanides (rare-earth elements), the opacity is lower and the emission appears bluer and peaks earlier.

- Red/Infrared Kilonova Phase (days to weeks): As heavier r-process elements dominate, line blanketing dramatically increases the opacity in the optical, shifting the emission toward the near-infrared. The light curve declines and reddens, often revealing multi-component structure.

- Afterglow (days to months+): The jet (or a mildly relativistic outflow) shocks the ambient interstellar medium, producing non-thermal synchrotron emission detectable in radio and X-rays. If the observer is significantly off-axis, the afterglow may rise slowly, peaking weeks to months later as the emitting region expands and decelerates.

This sequence is a blueprint, not a rigid script. Geometry matters. If we view the system off-axis, prompt gamma rays may be weak, while late-time radio reveals a structured jet. The presence or absence of a transiently stable neutron star remnant affects the energy injection and neutrino irradiation of the disk, which in turn changes the composition of outflows and the color evolution of the kilonova.

A helpful mental model for the multi-messenger timing is as follows:

Gravitational waves announce the dance, gamma rays whisper the jetnulls success, optical/IR light paints the composition, and radio/X-rays trace the shocknulls memory.

For observers and facilities that receive low-latency alerts, the first hours are crucial for catching the blue emission before it fades. Conversely, late follow-up is essential to capture the redder emission and afterglow, which constrain the ejectanulls heavy-element content and the jetnulls geometry.

Cosmic Alchemy: r-Process Heavy Elements from Mergers

Attribution: Babak Tafreshi; Inset: Dana Berry, SkyWorks Digital, Inc.

One of the most compelling aspects of neutron star mergers is their role in nucleosynthesis null the creation of new atomic nuclei. While stars forge lighter elements via fusion up to iron, and various supernova processes build some heavier nuclei, the rapid neutron capture process (r-process) is needed to create the heaviest elements on the periodic table.

The r-process requires environments with exceptionally high neutron densities so that atomic nuclei can capture neutrons faster than they beta-decay. In a merger, several ejecta channels can satisfy these conditions:

- Dynamical ejecta: Tidal torques fling out extremely neutron-rich material in the merger plane. This component tends to have a very low electron fraction (Ye), favoring the formation of lanthanides and actinides.

- Shock-heated ejecta: Near the collision interface, shocks heat material that can be ejected quasi-spherically, sometimes with a slightly higher Ye than purely tidal ejecta.

- Disk winds: Post-merger, the accretion disk around the remnant can drive outflows via neutrino heating, viscous dissipation, and magnetic stresses. If neutrino irradiation raises Ye, these winds can produce lighter r-process elements with fewer lanthanides.

These channels produce distinct opacity signatures. Lanthanides have complex electron structures leading to an enormous number of bound-bound transitions. The resulting line blanketing increases the opacity at optical wavelengths, redirecting the emission to red/near-infrared. Thus, a lanthanide-rich kilonova appears redder and peaks later than a lanthanide-poor one. The presence of both blue and red components in a single event can indicate multiple ejecta channels.

How much heavy material do mergers eject? Estimates from well-studied events suggest that a few hundredths of a solar mass of r-process material can be launched. Integrated over cosmic time, if neutron star merger rates are within observational bounds, these events could account for a substantial fraction of the universenulls r-process inventory. That said, there is evidence that other rare stellar explosions, such as certain collapsars (massive star collapses associated with long gamma-ray bursts), may also contribute. The relative contributions remain an active area of research, and observations of diverse events are essential for resolving this question.

Kilonova observations do more than tally the elements; they test nuclear physics under extreme conditions. The radioactive decay heating rate depends on the mix of isotopes produced, linking observed light curves to the underlying nuclear network. Spectroscopy, especially in the infrared, can reveal signatures of specific ions, though line identifications in such crowded spectra are challenging. Understanding these spectra informs nuclear physics far from stability, complementing laboratory experiments that probe r-process nuclei.

In short, neutron star mergers are a laboratory for violent astrophysical dynamics and for the slow cooling glow of freshly minted elements. The fact that you might be wearing atoms forged in such collisions imbues these distant events with a very human resonance.

Breakthrough Observations: GW170817, AT2017gfo, and Beyond

The modern picture of neutron star mergers crystallized with the 2017 detection of a binary neutron star inspiral by gravitational-wave observatories. Roughly two seconds after the merger time inferred from the gravitational-wave signal, space-based gamma-ray monitors detected a short burst, establishing a direct link between binary mergers and short gamma-ray bursts. Rapid follow-up localized a bright optical transient in an early-type galaxy about 40 Mpc away, designated AT2017gfo. This kilonova displayed the textbook color evolution: a blue component that peaked early and a redder component dominating days later.

Attribution: VLT/VIMOS. VLT/MUSE, MPG/ESO 2.2-metre telescope/GROND, VISTA/VIRCAM, VST/OmegaCAM

Multi-wavelength observations of this event yielded a trove of insights:

- Standard siren cosmology: Combining the gravitational-wave luminosity distance with the host galaxynulls redshift provided an independent estimate of the Hubble constant. While the uncertainty was large for a single event, this nullstandard sirennull approach is a key pillar of future cosmological measurements.

- Tidal deformability constraints: The gravitational waveform favored a range of tidal deformabilities that disfavor very stiff equations of state, offering independent constraints alongside X-ray radius measurements.

- Relativistic jet structure: Radio and X-ray afterglows rose slowly, consistent with an off-axis view of a structured jet. High-resolution radio imaging revealed apparent superluminal motion, reinforcing the jet interpretation.

- r-Process yields: Modeling of the light curve suggested multiple ejecta components totaling a few hundredths of a solar mass, with a lanthanide-rich component responsible for the near-infrared emission.

Subsequent gravitational-wave observing runs have cataloged additional compact binary mergers, including candidates with component masses consistent with neutron stars. However, not all have yielded electromagnetic counterparts, due to factors such as larger distances, sky localization areas, observational constraints, off-axis viewing geometries, and possibly prompt collapse scenarios that diminish or delay bright emission. Meanwhile, gamma-ray and optical surveys have reported kilonova candidates associated with some bursts, including cases where unusually long-duration gamma-ray emission appears to come from mergers rather than from massive star collapses. These cases highlight the diversity of engines and environments.

What makes these observations transformative is the synergy across messengers and wavelengths. Gravitational waves provide the dynamical backbone: masses, spins, and coalescence time. Optical/IR photometry and spectroscopy map the ejecta and composition. X-rays and radio trace the external shock and jet geometry. Together, they close loops in theory: the same mass and spin parameters that shape the merger dynamics also govern the mass of the accretion disk, which powers the jet and outflows that set the kilonovanulls spectral energy distribution.

These observations also motivate targeted theory and laboratory work. For example, interpreting the kilonova spectrum requires atomic data for ions of lanthanides at temperatures and densities relevant to ejecta. Continued improvements in atomic line lists and radiative transfer modeling are needed to transform spectra into precise abundance measurements.

Looking ahead, the growing network of gravitational-wave detectors and time-domain telescopes promises richer samples. Better localization will allow earlier optical discovery, and improved sensitivity will expand the volume in which we can find mergers. This will refine inferences about rates, EoS constraints, and the r-process budget.

How Kilonova Light Curves Reveal Ejecta Mass and Composition

Reading a kilonovanulls light curve and spectrum is akin to forensic analysis. The shapes of the light curves in different bands, their timescales, and color evolution all encode the ejectanulls mass, velocity, and composition. Here are the principal diagnostics:

- Peak time and brightness: For homologously expanding ejecta, the diffusion time scales roughly with opacity and mass, and inversely with velocity. A brighter, earlier peak in optical bands often points to a lower-opacity, lanthanide-poor component with modest mass and relatively high velocity.

- Color evolution: Rapid evolution from blue to red suggests the superposition of at least two components: an early, higher-Ye component (disk winds or shock-heated material) and a later, lanthanide-rich component (dynamical ejecta) with higher opacity.

- Spectral features: Identifying individual lines is challenging due to line blending, but broad features and overall spectral slopes reveal temperature and opacity trends. Near-infrared spectra are particularly valuable for constraining lanthanide-rich material.

- Late-time behavior: As the ejecta become optically thin, the decline rate can inform the radioactive heating rate and thermalization efficiency of decay products, linking observations to nuclear physics.

Attribution: ESO/E. Pian et al./S. Smartt & ePESSTO

To translate observations into physical parameters, researchers employ radiative transfer models informed by atomic data and nuclear decay heating rates. A successful fit might require:

- A blue component: low lanthanide fraction, relatively low opacity, fast rise, short-lived.

- A red component: high lanthanide fraction, higher opacity, slower rise, longer-lived emission peaking in near-IR.

- Anisotropy: viewing angle effects, with polar regions receiving more neutrino irradiation (higher Ye, bluer) and equatorial regions dominated by tidal ejecta (lower Ye, redder).

A representative finding from well-observed events is an ejecta mass totaling a few percent of a solar mass split between components with different opacities. Velocity estimates often fall in the range of a few tenths of the speed of light for the fastest ejecta and lower for disk-driven winds. While the exact numbers vary event by event, the recurring patterns strengthen the model of multi-component ejecta channels tied to merger dynamics and remnant survival time.

Importantly, the best-studied case demonstrated that a simple one-component model was inadequate. Dominant early blue light gave way to redder emission as higher-opacity material took over, and the late-time near-infrared data anchored the mass in the lanthanide-rich component. This multi-phase evolution unambiguously pointed to the presence of heavy r-process material.

As data improve, we can hope to glean even more detailed insights: constraints on specific element groups, signatures of actinide production, and tighter bounds on the distribution of Ye throughout the ejecta. Each of these improvements turns kilonovae into better laboratories for both astrophysics and nuclear science.

The Future of Multi-Messenger Astronomy

Multi-messenger astronomy combines gravitational waves with light across the spectrum to build a more complete picture of cosmic events. For neutron star mergers and kilonovae, the next decade promises substantial progress on several fronts:

Attribution: NOIRLab/LIGO/NSF/AURA/T. Matsopoulos

- Gravitational-wave detector upgrades: Ongoing improvements in sensitivity and duty cycle at observatories will extend the horizon distance for neutron star mergers and increase event rates. Better low-frequency sensitivity sharpens measurements of tidal deformability and mass ratio, improving constraints on the equation of state.

- Wide-field optical surveys: Next-generation surveys will scan large areas of the sky rapidly, crucial for finding optical counterparts within large localization regions. Robotic telescopes and follow-up networks will help triage candidates efficiently.

- Infrared capability: Because kilonovae often peak in the near-infrared, especially when lanthanide-rich, facilities with strong IR sensitivity and rapid response will be vital.

- High-energy observatories: Gamma-ray and X-ray satellites with fast alerts are essential for catching prompt emission and afterglows, constraining jet physics and viewing angles.

- Radio arrays and VLBI: Radio follow-up probes the kinetic energy of the outflow and resolves jet structure through apparent superluminal motion and late-time expansion, providing geometric constraints complementary to optical/IR light curves.

With larger samples, we will address several open questions:

- What fraction of neutron star mergers launch successful jets? And how often do we view them on- or off-axis?

- How does the remnantnulls survival time affect ejecta and kilonova colors? Does a longer-lived neutron star remnant systematically produce brighter blue components?

- What is the distribution of ejecta masses and compositions? Do environmental factors like host galaxy type or metallicity influence the r-process yields?

- How do mergers compare to alternative r-process sources? With more events, we can weigh the contributions of mergers against rare massive star explosions to the cosmic inventory of heavy elements.

Another frontier is standard siren cosmology. With multiple well-localized events and host galaxy redshifts, the Hubble constant can be measured independently of traditional distance ladders. This offers a valuable cross-check on potential tensions between methods. Even events without identified electromagnetic counterparts can contribute statistically through cross-correlations with galaxy catalogs.

All these advances rely on coordination: low-latency alerts, global follow-up networks, and data sharing platforms. As infrastructure and software pipelines mature, the lag between gravitational-wave detection and electromagnetic discovery will shrink, allowing us to capture the earliest phases that are most sensitive to composition and geometry.

How Amateurs and Citizen Scientists Can Follow Kilonovae

Kilonovae sit at the edge of amateur detectability, but motivated observers and citizen scientists can contribute meaningfully to the hunt and to follow-up campaigns. While the first kilonova was bright enough at peak to be recorded with modest telescopes, more distant events will be fainter. Nonetheless, there are roles for amateurs in data triage, rapid imaging, and monitoring.

Ways to engage responsibly and effectively:

- Follow alerts and broker summaries: Public alert streams and community brokers summarize gravitational-wave candidates and potential electromagnetic counterparts. These services distill large localization regions into prioritized targets.

- Use robotic networks: Some observatories and networks allow coordinated response to alerts. Even small telescopes can contribute by imaging candidate hosts for new transients and providing time-series photometry.

- Contribute to the Transient Name Server (TNS): The TNS is a central repository for transient discoveries and classifications. Amateur contributions can be valuable, especially for nearby events.

- Coordinate, donnullt crowd: Avoid duplicating efforts on the same field when collaboration can cover more ground. Use shared logs and check target lists before slewing.

Realistic expectations are important. Many gravitational-wave localizations span hundreds of square degrees; systematically covering such areas is difficult for small telescopes. However, targeted imaging of nearby galaxies within the localization can be efficient and rewarding. For bright, nearby events, sustained monitoring with modest apertures can capture the color changes that distinguish kilonovae from supernovae. Documenting non-detections at specific times and depths can also help constrain models by mapping upper limits on early blue emission.

For those more computationally inclined, processing alert streams, cross-matching with galaxy catalogs, and flagging promising candidates for larger telescopes is a powerful way to contribute. Open-source tools make it feasible to build simple pipelines. For example, a pseudo-workflow might look like:

# Pseudocode: reacting to a gravitational-wave alert

on_alert(event):

if event.classification == 'BNS' or event.possible_contains_neutron_star:

tiles = create_tiling(event.skymap, limiting_mag=20.0)

prioritized_galaxies = rank_galaxies(tiles, distance<200 Mpc)

for g in prioritized_galaxies:

if not recent_images(g.position):

request_imaging(g.position, filters=['r','i','z'])

listen_for_gamma_ray_coincidences()

subscribe_to_candidate_reports()Combined with community coordination, these activities fold amateurs into the broader multi-messenger ecosystem. When a nearby merger occurs, younullll be ready to capture crucial early data and to compare your light curves with the predicted evolution discussed in the kilonova modeling section.

Frequently Asked Questions

Do neutron star mergers create most of the universenulls gold?

Neutron star mergers are a leading site for the r-process that produces gold and other heavy elements. Observations of well-studied events show that mergers can eject significant masses of r-process material. Integrated over cosmic history, and given plausible event rates, mergers could account for a large fraction of the heavy elements. However, there is also evidence that certain rare types of massive star explosions may contribute. Determining the relative roles of these sources remains an active research frontier. A larger sample of mergers with well-characterized kilonovae will help resolve the balance.

Are all short gamma-ray bursts caused by neutron star mergers?

Many short gamma-ray bursts are consistent with originating from neutron star mergers, supported by the temporal coincidence with a gravitational-wave event and the discovery of an accompanying kilonova in at least one case. However, diversity exists in both duration and spectral properties, and viewing geometry can complicate classification. Some events with longer durations have shown evidence suggestive of merger origins, indicating that the mapping between duration class and progenitor is not one-to-one. Careful, multi-wavelength follow-up is essential for robust associations.

Final Thoughts on Understanding Neutron Star Mergers

Neutron star mergers and their kilonovae bind together fundamental physics and cosmic storytelling: the tremor of spacetime from a relativistic dance, the jetnulls brief flash, and the lingering glow of freshly forged elements. They allow us to test general relativity, probe the equation of state of dense matter, and trace the origins of the heaviest elements. The exemplary case of a nearby merger revealed how gravitational waves, gamma rays, optical/IR light, X-rays, and radio each contribute a chapter to the narrative, and how together they constrain the physics far better than any single messenger could.

As detectors and survey telescopes sharpen their capabilities, we can expect a richer census of events: some bright and blue, others red and infrared-dominated, some with clear jets and others cloaked by geometry or prompt collapse. Each will refine our understanding of merger rates, nucleosynthesis yields, and the demographics of host galaxies. With enough well-observed events, we can weigh the contributions of mergers against other candidate r-process factories and continue to tighten constraints on the neutron star equation of state via tidal effects in gravitational waves.

If this exploration has sparked your curiosity, consider diving deeper into multi-messenger astronomy, following public alert streams, and reading community reports when the next event unfolds. For more science-rich articles like this, including practical guides on observing transients and updates on the latest discoveries, subscribe to our newsletter and join us as we explore the evolving universe of compact objects and cosmic alchemy.