Table of Contents

n

- n

- What Is Europa, Jupiter’s Ocean Moon?

- Formation and Interior Structure of Europa

- Fractures, Ridges, and Chaos: Europa’s Surface Geology

- A Global Subsurface Ocean and the Case for Habitability

- Tidal Heating, Induced Magnetism, and Why Scientists Infer an Ocean

- Radiation, Surface Chemistry, and the Oxidant Pipeline

- From Voyager to Europa Clipper and JUICE: Missions and Observations

- How Europa Compares with Enceladus, Ganymede, and Other Ocean Worlds

- How to See Europa from Earth: Amateur Observing Tips

- Key Research Questions and What We Expect to Learn Next

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Final Thoughts on Exploring Europa, Jupiter’s Ocean Moon

n

n

n

n

n

n

n

n

n

n

n

n

nn

What Is Europa, Jupiter’s Ocean Moon?

n

Europa is one of the four large Galilean moons of Jupiter—Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto—first recorded by Galileo Galilei in 1610. With a diameter of about 3,121.6 kilometers (1,940 miles), Europa is slightly smaller than Earth’s Moon yet unique among major solar system bodies for being a likely global ocean world covered by an icy shell. Underneath its relatively smooth, bright surface, evidence indicates a worldwide, salty ocean that could contain more liquid water than all of Earth’s oceans combined.

n

n

nnn

Europa orbits Jupiter at an average distance of roughly 670,900 kilometers (about 417,000 miles) and completes a revolution in about 3.55 Earth days. Like many large moons, Europa is tidally locked, which means the same hemisphere always faces Jupiter. The moon’s modest orbital eccentricity—maintained by a three-body orbital resonance with Io and Ganymede—produces tidal flexing that continuously kneads Europa’s interior, generating heat that may help keep the ocean in a liquid state. This tidal energy is central to understanding Europa’s geology and potential habitability and is discussed in detail in Tidal Heating, Induced Magnetism, and Why Scientists Infer an Ocean.

n

Since the first close-up views by the Voyager spacecraft in 1979, Europa has emerged as one of the most compelling targets in planetary science. The Galileo mission (1995–2003) revolutionized our picture of this icy world by revealing its intricate network of dark lineae (fractures and ridges), areas of chaotic terrain, and a compelling magnetic signature consistent with a global conducting layer—likely a salty ocean—beneath the ice. Subsequent observations by the Hubble Space Telescope and ground-based observatories have hinted at episodic plumes, and new missions—including NASA’s Europa Clipper and ESA’s JUICE (Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer)—aim to address the most pressing questions about Europa’s interior, chemistry, and habitability.

nn

Formation and Interior Structure of Europa

n

Europa likely formed within Jupiter’s circumplanetary disk over 4 billion years ago. This formation environment would have been rich in water ice and rocky material, naturally leading to a differentiated body with a rocky/metallic core, a silicate mantle, a global ocean, and an outer ice shell. Europa’s bulk density—about 3.01 g/cm3—is higher than that of purely icy objects and indicates a significant rock fraction.

n

Although we cannot directly see Europa’s interior, multiple lines of evidence point toward a layered structure:

n

- n

- Metallic core: A small iron-rich core is plausible based on Europa’s density and comparisons with other differentiated moons.

- Silicate mantle: Above the core, a rocky mantle provides a potential site for water–rock interactions that could fuel geochemical energy sources for life, such as serpentinization or hydrothermal activity.

- Global subsurface ocean: Geophysical models, Galileo magnetometer data, and surface geology imply a global liquid layer. The ocean is expected to be salty, enhancing electrical conductivity, as discussed in Induced Magnetism.

- Outer ice shell: Europa’s outermost layer is water ice. The thickness of this shell has been debated for decades, with estimates ranging from a few kilometers to a few tens of kilometers. Many current models favor an ice thickness on the order of tens of kilometers, but it likely varies spatially, with thinner regions near geologically active areas. Future radar sounding by missions described in From Voyager to Europa Clipper and JUICE is expected to constrain this more precisely.

n

n

n

n

n

Europa’s interior heat budget is dominated by tidal heating rather than long-lived radionuclides alone. This additional heating helps to explain the ocean’s persistence over geological timescales and surface expressions such as ridges and chaos terrain. For context, the heat flow at Europa’s surface has been estimated in the range of roughly 0.05–0.2 W/m2 in many models—orders of magnitude lower than the volcanic inferno of Io, yet sufficient, over time, to affect the ice shell’s rheology and maintain a liquid ocean.

n

In short, Europa’s internal architecture—a rock core and mantle overlain by a global ocean and ice shell—makes it one of the solar system’s prime candidates for habitable environments. The silicate mantle, in contact with liquid water, is particularly relevant to potential energy sources for life and is treated further in A Global Subsurface Ocean and the Case for Habitability.

nn

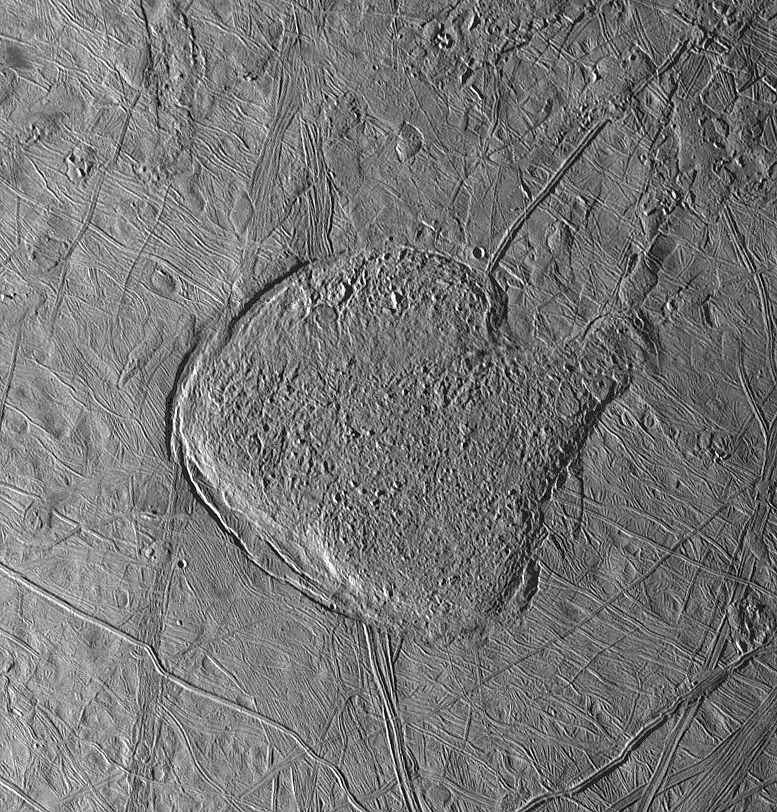

Fractures, Ridges, and Chaos: Europa’s Surface Geology

n

Europa’s surface is remarkably young by solar system standards, inferred from the scarcity of impact craters. While age estimates vary, many studies suggest resurfacing events have erased older terrains, producing a surface with an average age of tens of millions of years. This youthfulness is a strong hint that internal processes—driven by tidal heating—are active or were active in the geologically recent past.

n

Several distinct geologic features characterize Europa:

n

- n

- Lineae (fractures and ridges): Europa is crisscrossed by dark, linear features that span hundreds to thousands of kilometers. Double ridges—paired ridges separated by a trough—are common. Their formation mechanisms have been an active area of research. Proposed processes include diurnal tidal flexing that opens and closes cracks; pressurized brine intrusions that refreeze, uplifting ridges; and shallow water pockets in the ice shell that drive cyclical uplift. Terrestrial analogs in Greenland have inspired models where near-surface water refreezes and repeatedly pressurizes to create double ridges.

- Chaos terrain: These are jumbled, blocky regions where ice plates appear to have broken apart, rotated, and refrozen within a matrix of finer-grained material. Chaos terrains may signal local thinning of the ice shell, brine infiltration, or melting from below. Some chaos regions, such as those with distinctive coloration, have been linked to salts or hydrated materials brought up from the interior or redistributed by surface processes.

- Lenticulae (small domes and pits): Dotted across Europa’s surface are spots and pits that may be formed by diapirs—warm, buoyant ice rising through the colder surrounding shell—or by brine sills and melt-through mechanisms. These small-scale features hint at convection or localized heating within the shell.

- Scarcity of high-relief mountains: The overall low topography—aside from ridges and blocks—implies that the ice shell deforms more plastically than a rocky crust would. Gravity relaxation, ice viscosity, and resurfacing combine to reduce long-lived, high-standing features.

n

n

n

n

n

n

nnn

Spectrally, Europa’s surface is dominated by water ice with accompanying signatures that have been interpreted as hydrated salts or other compounds. Early analyses favored magnesium sulfate hydrates, while later observations, including high-quality ground-based spectra, suggested sodium chloride (table salt) may be abundant in certain regions, potentially explaining a yellowish tint. The exact mineralogy likely varies across terrains, reflecting a complex interplay of endogenic and exogenic processes.

n

It is crucial to note that Europa’s surface is also affected by Jupiter’s radiation environment and material originating from Io, which deposits sulfur species onto Europa’s leading hemisphere. This exogenic input complicates the spectral fingerprints of Europa’s endogenous chemistry, a challenge that future missions will tackle with higher-resolution, spatially targeted measurements, as outlined in Missions and Observations.

nn

A Global Subsurface Ocean and the Case for Habitability

n

The central question that elevates Europa’s scientific interest is its potential habitability. Habitability is not a claim of life’s presence but a statement about the environment’s capability to support life as we understand it. For a world to be habitable, key ingredients typically include liquid water, energy sources, essential elements (C, H, N, O, P, S), and time for chemistry to proceed and stabilize.

n

Evidence strongly supports the presence of a vast liquid ocean beneath Europa’s ice. Conductive ocean models, magnetic field data, and plausible heat budgets converge on a scenario where global water exists in contact with a rocky mantle. If true, this configuration would enable water–rock interactions that can generate chemical disequilibria—one of the primary drivers of metabolism in life on Earth. On Earth, hydrothermal vents at the seafloor provide habitats rich in chemical energy, independently of sunlight.

n

Europa’s potential habitability depends on several interrelated factors:

n

- n

- Liquid water reservoir: The ocean may be tens to more than a hundred kilometers deep. Even at the lower end of estimates, Europa could host a volume of water comparable to several times Earth’s ocean volume because of its global extent and depth.

- Energy sources: Without sunlight penetrating the ice, life—as we know it—would rely on chemical energy. Potential energy sources include oxidation–reduction chemistry, radiolysis-derived oxidants (see Radiation and Chemistry), and hydrothermal activity at the seafloor.

- Essential chemistry: The ocean’s salinity, pH, and inventory of dissolved species (e.g., sulfates, chlorides, carbonates) influence the availability of nutrients and the ocean’s energy landscape. Salinity also boosts the ocean’s electrical conductivity, which is key to the magnetic signatures described in Induced Magnetism.

- Exchange between ocean and surface: A major unknown is how efficiently materials produced at the irradiated surface (notably oxidants) are transported into the ocean. Mechanisms could include brine percolation through fractures, subduction-like overturn, or regional melt-through events associated with chaos terrain or double ridges.

n

n

n

n

n

n

nnn

Scientists sometimes describe an nulloxidant pipelinenull that moves oxidants created at the surface by radiation into the ocean. When coupled with potential reductants from water–rock reactions at the seafloor, the ocean may sustain persistent redox gradients—chemical energy differences that microbial life could exploit. Estimating the magnitude of this pipeline is difficult, hinging on ice shell dynamics, permeability, and timescales of resurfacing.

n

Plumes—if present and active—would offer an accessible pathway for sampling ocean-derived material without drilling through the ice. Hints of water vapor plumes have been reported in some Hubble ultraviolet observations and in re-analyses of Galileo data, though episodicity and confirmation remain active research topics. Whether Europa has persistent plume vents like Saturn’s Enceladus is not yet established. The prospect of plume sampling is a major motivator for mission strategies discussed in Missions and Observations.

n

Ultimately, Europa is not merely wet; it appears to be a chemically dynamic world that brings together water, energy, and potentially reactive chemistry. These are the same categories of factors that sustain life in the most remote environments on Earth, making Europa one of the most enticing targets in astrobiology.

nn

Tidal Heating, Induced Magnetism, and Why Scientists Infer an Ocean

n

Europa’s interior heat and inferred ocean are closely tied to its gravitational relationship with Jupiter and the other Galilean moons. Europa is in a Laplace resonance with Io and Ganymede: as Io orbits Jupiter once, Europa orbits roughly twice, and Ganymede about once for every two Europa orbits—commonly described as a 1:2:4 resonance. This resonance maintains a small orbital eccentricity (approximately e nullnull 0.009), causing Europa to flex as it moves closer to and farther from Jupiter during each orbit.

n

This cyclic flexing dissipates energy as heat through internal friction, a process known as tidal heating. The amount of heat generated depends on Europa’s interior structure (e.g., the viscosity of the ice shell, the presence of water layers, and potential anelastic behavior of silicates). Over time, even modest heat input can keep the ocean from freezing solid, especially if the ice shell acts as an insulating blanket.

n

Beyond tidal heating, the most compelling evidence for a global, salty ocean comes from Europa’s magnetic environment. The Galileo spacecraft detected variations in Europa’s magnetic field consistent with an induced magnetic field. As Jupiter’s powerful magnetosphere sweeps past Europa—whose position relative to Jupiter’s magnetic field lines changes over time—a conductive layer inside Europa responds by generating secondary magnetic fields. The best explanation for such a response is a global ocean with significant salinity, providing the necessary electrical conductivity to support induced currents.

n

n

nnn

In simplified terms, an induced magnetic field can be modeled as a conductor inside a time-varying external field. The magnitude and phase of the induced field depend on the conductor’s thickness, conductivity, and geometry. Europa’s observed induced response fits models of a saline ocean tens of kilometers beneath the ice. Additional confirmation will come from dedicated magnetic and plasma instruments on future spacecraft (see From Voyager to Europa Clipper and JUICE), which can better separate internal signals from the complex external environment near Jupiter.

n

Because the induced field depends on ocean conductivity, combining magnetic data with gravity measurements, radar sounding, and thermal mapping can constrain not just the existence of the ocean but its properties—including salinity and depth. Those parameters are not mere details; they influence ocean circulation, heat distribution, and potential habitability.

nn

Radiation, Surface Chemistry, and the Oxidant Pipeline

n

Europa orbits deep within Jupiter’s magnetosphere, an environment teeming with energetic charged particles. These particles—electrons and ions—strike Europa’s surface, causing radiolysis: the splitting of molecules by radiation. Radiolysis of water ice produces oxygen and hydrogen, among other species. Some of the oxygen escapes to form a tenuous O2 exosphere and auroral emissions that have been observed remotely. Other oxidants, including possibly hydrogen peroxide and ozone, accumulate in the surface ice.

n

This process has two major implications:

n

- n

- Surface coloration and chemistry: Radiolysis products and implanted sulfur from Io’s volcanic output create a complex, spatially variable chemistry. The leading and trailing hemispheres can differ in composition due to the directionality of plasma bombardment and particle implantation, plus differences in micrometeorite weathering.

- Potential energy source for life: If oxidants generated at the surface are transported downward (by fractures, convection, or brine percolation), they could oxidize reduced species originating from the interior, creating chemical gradients (redox couples) that living organisms could exploit. The magnitude of this oxidant pipeline is uncertain, but it represents a plausible way to fuel life in an otherwise dark ocean.

n

n

n

The radiation levels at Europa’s surface are extreme by human standards. The daily dose can reach levels that would be lethal to unshielded humans in a short time—emphasizing the need for radiation-hardened spacecraft systems and careful mission planning. Yet, this harshness also means abundant radiolysis products that could, under the right circumstances, boost ocean habitability over geological timescales.

n

Europa’s surface temperatures are frigid: near the equator at local noon, they can rise to roughly 110 K (about −163 °C), while polar regions can be as cold as ~50 K (−223 °C). At these temperatures, ices are generally brittle, but warm anomalies—sources of thermal inertia or endogenic heat—can locally soften ice, contribute to ridge formation, and create potential sites of geologic activity. Thermal infrared observations, including those planned by Europa Clipper, help pinpoint such thermal anomalies.

n

From a chemical perspective, a plausible suite of compounds on or near the surface includes water ice, chlorides, sulfates, carbonates, and radiolysis products. Distinguishing between endogenous salts (brought up from the ocean or ice shell) and exogenous materials (implanted by Jupiter’s magnetosphere or delivered by micrometeorites) remains a central challenge. The answer matters for habitability, because it dictates whether we are seeing a record of subsurface chemistry or surface weathering products unrelated to the oceanic environment.

nn

From Voyager to Europa Clipper and JUICE: Missions and Observations

n

Our knowledge of Europa has grown through a combination of spacecraft encounters and telescopic observations. Each mission added crucial layers of data, from global imaging to spectrometry to magnetometry. Below is a concise historical arc:

n

- n

- Voyager 1 and 2 (1979): The first close-up images revealed a smooth, bright surface crosshatched by dark lines, immediately distinguishing Europa from heavily cratered moons. These images ignited speculation about a young, geologically active crust.

- Galileo orbiter (1995–2003): A transformative mission for Europa science. Galileo’s magnetometer detected signatures consistent with an induced magnetic field—a strong indicator of a global, electrically conducting (salty) ocean beneath the ice. Imaging showed diverse terrains, including lineae and chaos regions. Spectral data indicated water ice plus other materials that could be salts or hydrates.

- Hubble Space Telescope: Hubble observed Europa in ultraviolet and other bands, detecting the presence of a tenuous oxygen atmosphere and reporting evidence in some datasets consistent with transient water vapor plumes. Although plume activity remains under investigation, these results shaped strategies for future plume sampling.

- Ground-based observatories: High-dispersion spectroscopy and adaptive optics imaging (e.g., from Keck and other facilities) refined our understanding of surface composition, including suggestions of sodium chloride in specific regions. These facilities also track Jupiter system dynamics and Europa’s exosphere.

n

n

n

n

n

Two major missions will drive the next era of Europa exploration:

n

NASA’s Europa Clipper

n

Europa Clipper is designed to perform dozens of close flybys of Europa while orbiting Jupiter, gathering high-resolution data without lingering too long in the most intense radiation zones. At the time of writing, the mission was planned with a comprehensive instrument suite aimed at three overarching goals: (1) characterize the ice shell and subsurface ocean, (2) investigate the composition and chemistry of the surface and potential plumes, and (3) understand the geology and recent activity of the moon.

n

n

nnn

Europa Clipper’s payload includes instruments such as:

n

- n

- Europa Imaging System (EIS): Wide- and narrow-angle cameras for high-resolution mapping and context imagery, crucial for interpreting geology and identifying active sites.

- REASON (Radar for Europa Assessment and Sounding: Ocean to Near-surface): Dual-frequency ice-penetrating radar intended to probe the ice shell’s thickness and structure, and potentially detect subsurface water pockets.

- MISE (Mapping Imaging Spectrometer for Europa): An infrared spectrometer to map the composition of the surface and identify salts, organics, and other compounds.

- Europa Thermal Emission Imaging System (E-THEMIS): A thermal imager to detect temperature anomalies that may indicate endogenic activity or recent resurfacing.

- Europa-UVS: An ultraviolet spectrograph capable of detecting emissions from the tenuous atmosphere and potential plumes.

- MASPEX (Mass Spectrometer for Planetary Exploration/Europa): A high-resolution mass spectrometer to analyze the composition of gases and trace constituents during flybys, including possible plume material.

- SUDA (Surface Dust Analyzer): Designed to analyze tiny particles ejected from Europa’s surface, which could carry signatures of subsurface materials.

- Plasma and magnetic investigations: Instruments that will characterize Europa’s induced magnetic field and the surrounding plasma environment to disentangle external influences from internal signals.

n

n

n

n

n

n

n

n

n

Europa Clipper will not land; instead, it maximizes science return through repeated close passes, building a global data set while adhering to planetary protection protocols by avoiding prolonged operation in Europa’s immediate vicinity. Ending the mission safely—typically via disposal in a way that precludes accidental Europa impact—is a critical consideration due to the moon’s astrobiological significance, as noted in Key Research Questions.

n

ESA’s JUICE (Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer)

n

Launched in 2023, ESA’s JUICE mission targets the Jupiter system with a focus on Ganymede while also conducting flybys of Europa (and Callisto). JUICE carries a powerful suite of instruments—cameras (JANUS), spectrometers (MAJIS), radar (RIME), magnetometers (J-MAG), a laser altimeter (GALA), and others—to study icy moon interiors, surfaces, and environments.

n

Although JUICE prioritizes Ganymede (including an eventual orbit around Ganymede), its Europa flybys are strategically designed to investigate the moon’s surface composition, thickness of the ice, and local plasma environment. Combined data sets from JUICE and Europa Clipper—operating with different orbits, instruments, and observational geometries—promise a complementary and cross-validated picture of Europa’s habitability.

n

In the broader context of ocean worlds exploration, lessons from Saturn’s Enceladus (where Cassini directly sampled plumes) sharpen expectations and strategies for Europa. If Europa’s plumes are sporadic or weak, direct sampling during a flyby becomes more challenging, underscoring the importance of thermal mapping, radar sounding, and careful selection of flyby trajectories for maximum science return.

nn

How Europa Compares with Enceladus, Ganymede, and Other Ocean Worlds

n

Europa is not alone as a candidate ocean world. Several icy bodies across the outer solar system show evidence for subsurface oceans, but each offers a unique mixture of heat sources, chemistry, and transport processes. Understanding these differences deepens our interpretation of Europa’s data.

n

n

nnn

- n

- Europa vs. Enceladus: Saturn’s moon Enceladus definitively vents water-rich plumes from its south polar terrain, enabling direct sampling by the Cassini spacecraft. Enceladus is smaller than Europa but exhibits clear endogenic activity and hydrothermal signatures (e.g., silica nanoparticles interpreted as evidence for high-temperature water–rock interactions). Europa’s suspected plumes are less certain and possibly transient. However, Europa’s larger size and stronger tidal heating could support a deeper, long-lived ocean with potentially greater seafloor area for hydrothermal activity.

- Europa vs. Ganymede: Ganymede, the largest moon in the solar system, possesses a magnetic field generated by an internal dynamo and likely harbors a layered ocean. However, Ganymede’s thicker ice shell and different thermal history suggest a more insulated ocean with potentially more stratification. JUICE will probe Ganymede extensively, providing context for Europa’s more geologically youthful face.

- Europa vs. Callisto: Callisto appears more heavily cratered and less geologically active, though it may also contain a subsurface ocean. Its older surface implies a lower rate of resurfacing compared to Europa, contrasting with Europa’s dynamic shell.

- Europa vs. Titan: Saturn’s moon Titan hosts surface liquids (hydrocarbon lakes and seas) and a likely subsurface water ocean beneath an ice shell. Titan’s dense, organic-rich atmosphere and complex chemistry represent a different avenue for habitability, one dominated by surface hydrocarbon chemistry and atmospheric photochemistry, rather than the intense radiation-driven surface chemistry of Europa.

n

n

n

n

n

The “family portrait” of ocean worlds highlights diverse pathways to habitability. Some worlds (like Enceladus) present accessible plumes; others (like Europa) may require deeper geophysical sleuthing through radar and magnetometry. Europa’s relative youth, global ocean, and access to oxidants via radiolysis make it an especially intriguing target even without confirmed persistent plumes.

nn

How to See Europa from Earth: Amateur Observing Tips

n

While probing Europa’s ocean requires spacecraft, amateur astronomers can observe Europa’s dance around Jupiter with modest equipment. Europa appears as a faint starlike point next to Jupiter, visible in small telescopes and even high-quality binoculars under steady skies. Observing Jupiter’s moons over multiple nights reveals their rapid motion and orbital mechanics firsthand.

n

Here are practical tips for seeing Europa:

n

- n

- Use a stable mount and moderate magnification: Jupiter is bright and easy to locate. A small telescope (e.g., 70–100 mm aperture) at 50–150× magnification can resolve the four Galilean moons as distinct points. Larger apertures and steady seeing yield crisper views.

- Track mutual events: Europa regularly undergoes transits across Jupiter’s disk, as well as occultations and eclipses. A transit occurs when Europa passes in front of Jupiter; its small, dark shadow may also be seen crossing Jupiter’s cloud tops in good conditions. Ephemerides from reputable sources let you plan observations of these events.

- Follow the order of the moons: With practice, you can identify which point of light is Europa by comparing their distances from Jupiter and using timing predictions. Europa is typically the second closest to Jupiter after Io in apparent separation, but configurations change daily.

- Photograph the system: Short-exposure smartphone or planetary camera images through a small telescope can record the positions of the Galilean moons. While detailed surface features of Europa are beyond amateur reach, imaging their changing positions over an evening is rewarding and educational.

n

n

n

n

n

Observing Jupiter’s moons offers a tangible connection to the orbital resonance that powers tidal heating on Europa. Watching Europa transit, occult, or cast its shadow on Jupiter is a reminder that—even from a backyard—one can witness dynamics that shape the moon’s internal energy budget.

nn

Key Research Questions and What We Expect to Learn Next

n

Despite decades of study, crucial questions about Europa remain open. Tackling these will require the synergy of flyby missions, telescopic monitoring, and theoretical modeling:

n

- n

- How thick is the ice shell, and how variable is it? Ice thickness may vary substantially across Europa, with thinner regions near active areas. Ice-penetrating radar from Europa Clipper aims to map layering and detect subsurface water pockets or brine lenses. Understanding the shell’s thickness distribution is essential for interpreting surface geology and estimating transport timescales for the oxidant pipeline.

- Are there active plumes? Confirming plume activity—its frequency, intensity, and composition—would profoundly shape exploration strategies. Plumes could enable direct sampling of subsurface materials during flybys with instruments like MASPEX and SUDA. If plumes are sporadic, mission plans might be adapted to increase the probability of plume passage and capture.

- What is the ocean’s salinity and chemistry? The induced magnetic response constrains conductivity; combined with spectroscopy and thermal mapping, these data can narrow down plausible ocean compositions (e.g., chloride-dominated vs. sulfate-dominated). Ocean composition influences density stratification, circulation, and chemical energy availability.

- Is there ongoing hydrothermal activity at the seafloor? Indirect indicators include specific elemental or isotopic ratios in plume material (if sampled), thermal anomalies, or spectral hints of ocean-sourced salts. While direct imaging of the seafloor is beyond current mission capabilities, geophysical and chemical data can reveal whether hydrothermal systems are likely.

- How does the ice shell exchange material with the ocean? Double ridges, chaos terrains, and lenticulae could serve as conduits for brines. Pinpointing the mechanisms—diapirs, sills, fracture pumping, localized melt-through—will clarify how nutrients and oxidants move between the surface and ocean.

- What is the level of geological activity today? Fresh-appearing ridges, warm spots detected by thermal instruments, or changes observed over time can reveal present-day activity. Even small changes—seasonal or orbital—can be diagnostic of internal processes.

- Planetary protection and future access: Europa is a high-priority target for astrobiology. Protecting it from terrestrial contamination is crucial. This complicates mission designs for landers or penetrators and will influence how and when surface or subsurface access is attempted. Flyby missions like Europa Clipper are a prudent step while we build knowledge and technologies for future, more ambitious exploration.

n

n

n

n

n

n

n

n

The combined efforts of Europa Clipper and JUICE are poised to shrink uncertainties across these domains. While neither mission includes a lander, their datasets—magnetometry, radar, spectroscopy, imaging, and in situ sampling of dust and gases—could decisively answer whether Europa hosts an ocean suitable for life and whether exchange processes can bring ocean materials to the surface.

nn

Frequently Asked Questions

n

Is Europa confirmed to have a liquid ocean?

n

Multiple lines of evidence strongly support a global, saline ocean beneath Europa’s ice. The induced magnetic field signal detected by Galileo is best explained by a conductive, global liquid layer. Surface geology—such as widespread lineae and chaos terrain—also indicates an active ice shell influenced by internal processes. While we have not directly imaged the ocean, the convergence of magnetic, geological, and thermal evidence makes the ocean the leading explanation. Upcoming missions will tighten constraints on ocean depth, salinity, and ice thickness to further confirm and characterize it.

n

Could life exist in Europa’s ocean?

n

Europa’s ocean has the key ingredients that, on Earth, support life: liquid water, chemical energy sources, and time. Potential energy could come from water–rock interactions at the seafloor (e.g., hydrothermal systems) and from oxidants produced by surface radiolysis that reach the ocean. The central question is whether sufficient chemical disequilibria persist to sustain metabolism. We do not yet know the answer, but the habitability potential is high enough to make Europa one of the most important targets for astrobiology.

nn

Final Thoughts on Exploring Europa, Jupiter’s Ocean Moon

n

Europa stands at the crossroads of planetary science and astrobiology. It is a world where ice meets ocean, where tidal forces sculpt a crust that records interactions between surface and interior, and where the chemistry produced by Jupiter’s fierce radiation could ultimately energize a hidden biosphere. The case for a global ocean is compelling; evidence for geologic youth and resurfacing is persuasive; the habitability potential—while unproven—remains one of the most enticing in the solar system.

n

The next decade promises a major leap forward. By combining the strengths of Europa Clipper’s targeted flybys with JUICE’s broader Jupiter system context, scientists will piece together a far more detailed narrative: how thick Europa’s ice shell is and how it varies, whether plumes offer windows into the ocean, what salts and organic compounds pepper the surface, and how magnetic, thermal, and geological signals cohere into a unified model of Europa as an ocean world.

n

For the public and the astronomy community, Europa is a beacon of exploration—one that reminds us that oceans can thrive in the dark, far from the warmth of a star. If you’re curious about the latest findings, mission milestones, and the evolving story of ocean worlds, consider subscribing to our newsletter. We’ll continue to explore Europa’s science, compare it with other icy moons, and highlight the data as it arrives—step by step, orbit by orbit—bringing this distant ocean world into clearer focus.