Welcome to our guide on the constellation Andromeda! This stellar formation is located in the Northern Hemisphere of our night sky and can be seen from any part of the world. Named after a princess from Greek mythology, this star pattern has been used for centuries by various cultures to mark seasonal changes and keep track of time. In this guide, you will learn about Andromeda’s history and its many interesting features, such as its brightest stars, deep-sky objects, mythology, and more. So get ready for a journey as we explore this stunning constellation together.

Contents

Mythology & Location

The constellation Andromeda is named after a character from Greek mythology—the princess Andromeda. According to the myth, she was the daughter of King Cepheus and Queen Cassiopeia of Ethiopia. When Cassiopeia boasted that her beauty was superior to that of all other sea nymphs, Poseidon became angry and sent a monstrous sea creature called Cetus to ravage their lands as punishment. Cepheus consulted an oracle to appease him, advising them to sacrifice their daughter Andromeda to the beast.

Andromeda was chained to a rock on the coast with no hope for salvation until Perseus (a demigod best known for slaying the Gorgon Medusa) arrived on his winged horse Pegasus and slew Cetus before freeing her. In gratitude, Cepheus offered his throne in marriage and half of his kingdom. Afterward, they were placed in heaven among stars by Zeus so they would never be forgotten—thus creating two constellations; one for each of them—and inspiring stories about star-crossed lovers throughout time.

The actual constellation of Andromeda is easily confused with Pegasus, which it borders. The asterism of the “Great Square” of Pegasus appears to have “arms” of stars extending on both sides; the northern one makes up the constellation Andromeda.

Stars

Andromeda is home to many bright stars, the brightest of which are Alpha Andromedae (Alpheratz) and Beta Andromedae (Mirach). These two stars appear in the center of the constellation. Alpha Andromeda, also known as Almaak or Alpheratz, is a bluish giant star about 98 light years away, shining at magnitude 2. Beta Andromedae, or Mirach, is a red giant star located about 200 light-years from Earth. It has a similar apparent brightness to Alpheratz at right around magnitude 2, and shines with a reddish hue that distinguishes it from other stars in Andromeda. A bit dimmer at magnitude 2.3 is Gamma Andromedae, commonly referred to as Almach, which is a quadruple star system. The three stars of Ba, Bb, and C cannot usually be resolved with a ground-based telescope. Still, the stars can be split into a yellow-orange component (A) and a white component (B stars and C) in even fairly small telescopes at magnifications of 75x or more.

One of the next most prominent stars in the Andromeda constellation is Upsilon Andromedae, a 4th magnitude white F-class star located approximately 44 light years away. The system includes four planets in orbit around it – Saffar, Samh, Majriti, and an as-yet-unnamed fourth planet. All are massive gas giant planets bigger than Jupiter; Samh is big enough – 14 Jupiter masses – that it may be a brown dwarf or “failed star,” while Majriti is not too far off at ten times Jupiter’s mass. All three have highly irregular orbits – Samh’s orbit is elongated like Mars. Majriti is an extremely elongated and inclined orbit similar to Pluto’s around the star. Saffar’s orbit is similarly inclined but nearly circular. Saffar’s proximity to Upsilon Andromedae has actually created a permanent sunspot-like feature on the star’s surface due to its gravitational pull. The three named planets were discovered in 1999 and are among the first exoplanets known to exist. A red dwarf star, 13th-magnitude Titawin, orbits the main star further out.

R Andromedae is a red giant star located at a distance of 200 light years from us. It has been studied extensively because of its high variability in brightness, ranging from magnitude 5 (easily naked eye visible under suburban and dark skies) to 15 (dimmer than Pluto, requiring a 10” or larger scope to see) over a 409-day period. This is caused as the star pulsates due to its unstable helium fusion as the star nears the end of its life.

Andromeda is home to many other spectacular double stars that can be seen with a small telescope. A few other ones are ideal targets for amateurs to view, even in light-polluted conditions. Pi And (magnitude 4.3) is easy to split with small scopes, at 36 arc seconds (a bit smaller than Jupiter’s angular diameter) apart and revealing a white and bluish-white component. Groombridge 34 (magnitude 8.1) is similar in separation though too dim to reveal many colors; this pair of red dwarfs is a mere 12 light-years away from our Solar System and has at least two exoplanets around A, the brighter of the two stars. Struve 79 is just next to the Andromeda Galaxy in the sky and, at magnitude 6, easily seen in binoculars; the white pair is eight arc seconds apart and easily separated with a small scope at 100x or higher magnification.

Deep-Sky Objects in Andromeda

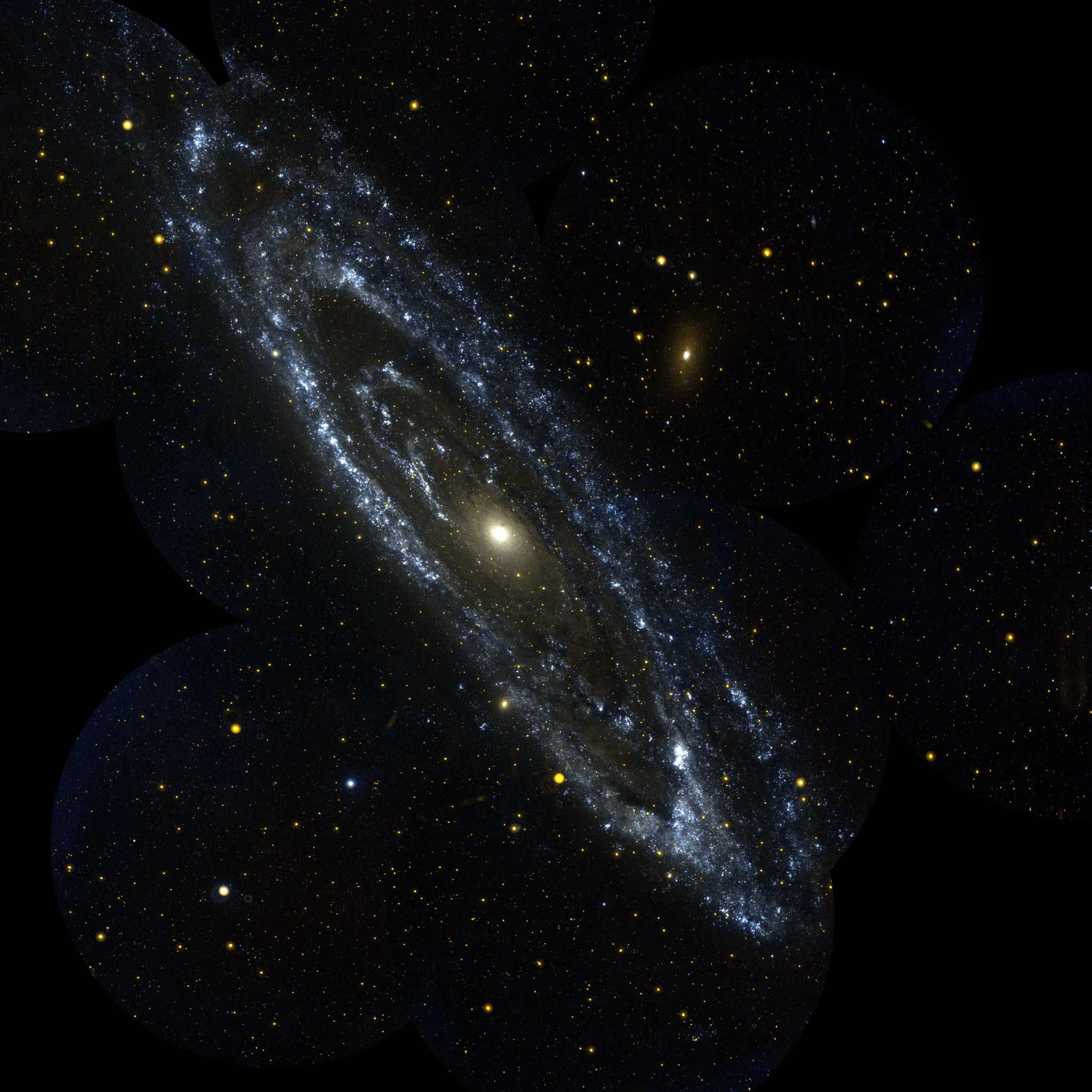

The most famous of all the deep-sky objects in Andromeda is the Andromeda Galaxy itself, also called M31. Roughly equal in size and shape to our own Milky Way, M31 is the nearest true spiral galaxy to us at about 3 million light-years away and is destined to collide with us a few billion years from now (by which time the Sun will have become a red giant and scorched the Earth, so there’s no need to worry). You can see it with the naked eye from suburban (Bortle 5) or darker skies and with binoculars anywhere. It is one of only a handful of galaxies visible to the naked eye and by far the easiest to see.

Finding M31: The easiest way to find the Andromeda Galaxy is by using the constellation Cassiopeia as a starting point. In the northern hemisphere, look for a large V-shaped asterism near one of the brightest stars in our night sky – Polaris, or “the North Star.” The Andromeda Galaxy will appear just below and slightly left of this asterism; if you continue to look downward and left from there, you should be able to spot it easily with your unaided eye or binoculars on clear nights. You may need some help at first if you are unfamiliar with how constellations look in different parts of the sky throughout different times of the year; some star charts can help immensely here!

Through a telescope or binoculars under light-polluted skies, M31 shows little detail. Its bright companion galaxy M32 is fairly conspicuous, while dimmer M110 can be tough to spot. M31’s core is about a degree, or twice the size of the full Moon and 4x the area, in size in the sky, while its disk spans about three degrees. Dark skies reveal the galaxy’s gigantic disk and dust lanes even in 70-80mm binoculars and telescopes. In contrast, a 12” or larger telescope brings out more detail in the lanes and star clouds, such as NGC 206, gaseous H-II regions, and globular clusters surrounding M31 itself. The brightest of these, G1 or Mayall II, sits about two degrees from M31’s core in the sky and can be seen with 10” telescopes, resolved into individual stars with monster 20” or larger instruments. At the same time, other Andromeda globulars remain faint fuzzies in very large scopes and can be difficult to detect with under 12” or aperture.

Besides M31 and its associated companion objects, a few other galaxies in Andromeda are of interest. NGC 891, the Needle, is visible in 6” and larger telescopes as a dim, thin streak with a dust lane just above its edge-on disk. NGC 891 is about 30 million light-years away – a spiral galaxy like Andromeda or our Milky Way. It is also similar in physical size.

Mirach’s Ghost (NGC 404) appears as a smudge next to Mirach and is easily mistaken for glare but can be seen with 4” and larger scopes under decent conditions. It is a small elliptical galaxy millions of light-years from anything else but is one of the closer galaxies to our own Milky Way at 10 million light-years away.

NGC 7640 is only visible under dark skies but is a nearly edge-on barred spiral that looks nice in 10” and larger scopes. It is about 39 million light-years away from us.

Andromeda is home to a few open star clusters – NGC 7686, NGC 752, NGC 272, and the “false” open cluster NGC 956. NGC 7686 is the brightest of these clusters and consists of 30 stars that can be observed with binoculars under dark sky conditions. Located within this cluster are several red giant stars that shine brightly in the night sky. NGC 752 contains approximately 80 stars and is visible with binoculars from a dark sky location. Within this cluster, two distinct regions contain different types of stars, which gives it an interesting appearance when viewed through a telescope. NGC 272 is a fairly small, unremarkable open cluster best seen in small scopes. Lastly, we have NGC 956, which is often overlooked due to its faintness compared to the other two clusters mentioned above. Technically an asterism rather than a true open cluster, it can only be seen with a 6” or bigger telescope from a dark sky site and consists of about 20-25 stars arranged in an arc formation.

Lastly, NGC 7662, or the “Blue Snowball,” is a planetary nebula in Andromeda. It is visible in small telescopes, but a 6” or larger instrument is needed to bring out its bluish color, a product of its ionized gas shell about a light-year across ejected from a dying star at its center. On a night of steady atmospheric conditions, a brighter ring within the main outer shell should be visible with larger scopes.