Table of Contents

- What Is the Summer Triangle Asterism?

- When and Where to See the Summer Triangle

- Meet the Stars: Vega, Deneb, and Altair

- Star-Hopping and Navigational Uses Across the Milky Way

- Deep-Sky Highlights Inside the Triangle

- Understanding the Milky Way Through the Triangle

- Observing Tips for Urban and Dark-Sky Viewers

- Cultural Footprints and Asterisms Related to the Triangle

- Gear, Filters, and Planning Tools for the Triangle

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Final Thoughts on Exploring the Summer Triangle

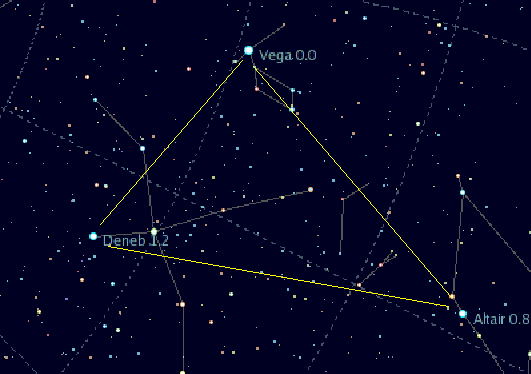

What Is the Summer Triangle Asterism?

The Summer Triangle is one of the sky’s most recognizable asterisms: a large, nearly isosceles triangle marked by three bright stars—Vega in Lyra, Deneb in Cygnus, and Altair in Aquila. Unlike formal constellations defined by the International Astronomical Union, an asterism is a popular star pattern that spans parts of several constellations. The Summer Triangle stitches together the northern Milky Way’s rich star fields and nebulae, providing both beginners and seasoned observers with a reliable seasonal landmark.

Attribution: Jim Thomas

This asterism is visible for much of the year in the Northern Hemisphere, most prominently on summer evenings—hence the name. Its triangle points anchor three separate constellations, each with its own deep-sky treasures and distinctive shapes:

- Lyra, home to Vega, features the compact “parallelogram” pattern and the famous Ring Nebula.

- Cygnus, anchored by Deneb, stretches as the “Northern Cross,” cutting directly through the Milky Way.

- Aquila, led by Altair, is flanked by two dimmer stars that form a striking line, while the nearby sky brims with dark nebulae and clusters.

The Summer Triangle is more than a sightseer’s guide; it’s a doorway into understanding the structure of our galaxy. The band of the Milky Way flows through the Triangle, and the dark dust lanes—the so-called Great Rift—splits its glow. As you explore the region, you will encounter star clusters, planetary nebulae, and supernova remnants, all embedded in the galaxy’s spiral architecture. To plan your tour, jump ahead to the curated list of targets under Deep-Sky Highlights Inside the Triangle and pair it with the techniques in Star-Hopping and Navigational Uses Across the Milky Way.

When and Where to See the Summer Triangle

Because Vega, Deneb, and Altair are among the brightest stars in the northern sky, the Summer Triangle is unusually easy to spot. That said, its visibility and altitude shift with the seasons and your latitude. Here’s a practical guide to timing and placement.

Northern Hemisphere timing

- May–June evenings: The Triangle rises in the east after dusk. By late June, it is well up by mid-evening.

- July–September evenings: Prime time. The Triangle is high overhead at mid-latitudes, often straddling the zenith in August.

- October–November evenings: The asterism shifts toward the west after sunset; still well placed through mid-evening.

- Winter pre-dawn: The Triangle reappears in the pre-dawn eastern sky, heralding the coming spring and summer skies.

Southern Hemisphere visibility

Much of the Summer Triangle is visible from temperate southern latitudes, though it rides lower in the northern sky and, in far-southern locations, one or more stars can sink below the horizon.

- ~30° S latitude: The Triangle is well placed in the northern sky during the Southern Hemisphere’s winter months (June–August). Altair is highest; Deneb is lowest.

- ~45° S latitude: Altair and Vega can be seen, but Deneb skims the northern horizon and may be difficult or impossible from obstructed sites.

- ~60° S latitude: Deneb is below the horizon; the full Triangle is not visible.

Light pollution and transparency

The Triangle is resilient against city lighting because its corner stars are bright. However, the Milky Way’s glow and the region’s delicate nebulae benefit enormously from dark, transparent skies. If you are planning a session targeting faint objects like the Veil Nebula or the North America Nebula, pair your timing with the darkest nights (new moon ± a few days) and the clearest, driest conditions you can find. For a list of objects that require darker skies, see Deep-Sky Highlights.

Meet the Stars: Vega, Deneb, and Altair

Each vertex of the Summer Triangle is a star with its own astrophysical story. Together, they span a striking range of distances and stellar types—an opportunity to compare a nearby main-sequence star, a distant supergiant, and a fast-spinning dwarf.

Vega (Alpha Lyrae): the blue-white standard-bearer

Vega is a bright, blue-white star in the constellation Lyra, shining at visual magnitude near 0. It sits about 25 light-years from Earth, making it one of our local stellar neighbors. Spectroscopically classified around A0 V, Vega has long been central to photometry as a reference star; in traditional systems, it helped anchor magnitude zero for several bands, though modern calibrations are more nuanced.

Vega rotates rapidly and presents a slightly oblate shape, with poles hotter than the equator. Infrared observations reveal excess emission from a debris disk, hinting at planetesimal belts and ongoing dust production. On Earth’s long precessional timescale, Vega will become a future pole star tens of centuries from now. Within Lyra, it helps observers find two classic targets: the Epsilon Lyrae “Double Double”, a celebrated multiple-star system near Vega, and the Ring Nebula (M57) tucked between Beta and Gamma Lyrae. For directions, jump to Deep-Sky Highlights.

Deneb (Alpha Cygni): a distant, luminous supergiant

Deneb crowns the tail of Cygnus the Swan and stands at the top of the “Northern Cross.” It is an A-type supergiant (often classified around A2 Ia). Its distance is substantial and carries uncertainties, but contemporary estimates place it on the order of a few thousand light-years from Earth—often cited around roughly 2,600 light-years. Because of this distance and its intrinsic brightness, Deneb is one of the most luminous first-magnitude stars visible to the naked eye, shining tens or even hundreds of thousands of times more brightly than the Sun depending on the exact distance adopted.

Deneb’s location makes it an excellent gateway into the Milky Way. The star sits near rich fields of emission nebulae—the North America Nebula (NGC 7000) and the Pelican Nebula (IC 5070)—and close to the dark nebulae that outline the Milky Way’s Great Rift. Deneb also lends its name to a class of slight, non-radial pulsators (Alpha Cygni variables), though its small variations are subtle to the eye. To explore targets in Deneb’s vicinity, see Deep-Sky Highlights and the observing strategies under Observing Tips.

Altair (Alpha Aquilae): a fast-spinning nearby star

Altair anchors the constellation Aquila and lies only about 17 light-years away. This A-type main-sequence star (often classified near A7 V) rotates extremely rapidly—on the order of some hours—producing a significant equatorial bulge and temperature differences across its surface. Interferometric studies have directly measured its oblate shape.

Altair’s brightness and proximity make it prominent even from cities. In the sky, look for two nearby stars, Tarazed and Alshain, forming a distinctive line with Altair. This trio is a convenient navigational cue for finding Aquila’s faint star clouds and the dramatic silhouette of the “E” Dark Nebula (Barnard 142 and 143) nearby. To use Altair as a jumping-off point for binocular and telescopic sweeps, see Star-Hopping.

Star-Hopping and Navigational Uses Across the Milky Way

Attribution: Tomruen at en.wikipedia

The Summer Triangle is a natural compass for the northern Milky Way. With a few simple hops, you can discover entire lanes of clustered stars and nebulae. The following routes are designed for naked-eye orientation first, then for binoculars or small telescopes.

Orient with the Triangle’s geometry

- Identify Vega—the brightest corner. From light-polluted sites, it may be the first star to appear at dusk.

- Trace from Vega toward the Milky Way band (a hazy stripe under dark skies) to reach Deneb.

- Drop down from Deneb toward the south-southeast to find Altair, completing the Triangle.

If you notice a cross-shaped pattern running through Deneb, you’ve found the Northern Cross. The star at the intersection (Sadr) sits in a star-cloud region overflowing with emission nebulae. This is covered in Deep-Sky Highlights.

Lyra: from Vega to the Ring Nebula

- From Vega, look for a small parallelogram of stars just to its south.

- Identify Beta Lyrae (Sheliak) and Gamma Lyrae (Sulafat)—the two bright stars on the long side of the parallelogram.

- Point binoculars or a small telescope midway between Sheliak and Sulafat to see a tiny, out-of-focus “smoke ring”: M57, the Ring Nebula.

- For a double-star treat, nudge to Epsilon Lyrae near Vega—the “Double Double”—which resolves into two pairs at moderate magnification and steady seeing.

Cygnus: flying the Northern Cross

- From Deneb, follow the long axis of the cross down to Albireo, the star at the Swan’s beak. Through small telescopes, Albireo is a classic color-contrast double.

- Return to Deneb and glide to Sadr (the center of the cross). The surrounding star fields are rich; scan slowly with binoculars.

- From Sadr, sweep east and west to detect faint nebulosity in dark skies—the Butterfly Nebula complex around IC 1318 and other H II regions.

Aquila and the dark “E”

- Start with Altair and trace the short line that includes Tarazed (orange) and Alshain.

- Move your binoculars north of Altair to search for dark lanes: the “E” Dark Nebula (Barnard 142 and 143) creates a blocky silhouette against the Milky Way glow under very dark skies.

- Continue scanning westward to encounter small open clusters such as NGC 6709 and, farther along the Milky Way, the arrow of Sagitta with the globular cluster M71 nearby (in Sagitta).

Tip: If you have trouble seeing the Milky Way, give your eyes 20–30 minutes to adapt. Use a dim red light and avoid phone screens or bright house lights before stepping outside.

Deep-Sky Highlights Inside the Triangle

The Summer Triangle spans a dense star zone with classic showpieces for every instrument level. Below, targets are grouped roughly by constellation and difficulty. Even if you observe from a city, many of these objects are attainable—especially double stars and bright globulars—while dark sites reveal faint nebulae in dramatic relief.

Lyra

- M57 (Ring Nebula): A planetary nebula lying between Sheliak (Beta Lyrae) and Sulafat (Gamma Lyrae). In small scopes it appears as a smoke ring; medium apertures begin to show a darker center. High magnification under steady seeing can suggest uneven brightness around the rim. Filters like O III or UHC can increase contrast. See also the sightline described under Star-Hopping.

This new image shows the dramatic shape and colour of the Ring Nebula, otherwise known as Messier 57. From Earth’s perspective, the nebula looks like a simple elliptical shape with a shaggy boundary. However, new observations combining existing ground-based data with new NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope data show that the nebula is shaped like a distorted doughnut. This doughnut has a rugby-ball-shaped region of lower-density material slotted into in its central “gap”, stretching towards and away from us.

Attribution: NASA, ESA, and C. Robert O’Dell (Vanderbilt University) - Epsilon Lyrae (the Double Double): A test of optics and seeing. At low power you’ll note two stars; higher magnification splits each into two, yielding four.

Cygnus

- Albireo (Beta Cygni): A famed color-contrast pair at the Swan’s beak, often showing golden and bluish components in small telescopes. While opinions differ on whether the stars form a gravitationally bound pair, the view is beautiful regardless.

- North America Nebula (NGC 7000) and Pelican Nebula (IC 5070): Emission nebulae near Deneb. Best at dark sites with wide-field binoculars or short focal length telescopes and a narrowband filter. Under good conditions, the “Gulf of Mexico” indentation is recognizable.

- Veil Nebula (NGC 6960/6992/6995): A large supernova remnant spanning multiple degrees in eastern Cygnus. The western portion threads near 52 Cygni; the eastern arcs are more filamentary. O III and UHC filters make an enormous difference.

NGC 6960 or the Veil Nebula is a cloud of heated and ionized gas and dust in the constellation Cygnus. The analysis of the emissions from the nebula indicate the presence of oxygen, sulfur, and hydrogen. This is also one of the largest, brightest features in the x-ray sky. It is the Western Veil of the nebula (also known as Caldwell 34), consisting of NGC 6960 (the “Witch’s Broom”, “Finger of God”, or “Filamentary Nebula”) near the foreground star 52 Cygni. The image details of NGC6960 is a three frame mosaic taken with 5 different filters, standard Red – Green – Blue with details enhanced with narrowband data of Hydrogen (Ha) and Oxygen (OIII).

Attribution: Ken Crawford - M39: A loose open cluster north-northeast of Deneb, best framed in binoculars or low-power telescopes.

- Sadr Region (IC 1318 complex): Around Gamma Cygni (Sadr), a network of faint emission illuminated by young, massive stars. A dark sky and filters help bring out structure.

Aquila and neighboring small constellations

- “E” Dark Nebula (B142/B143): Two dark clouds forming an E-shape northwest of Altair against the Milky Way glow. These require dark skies and patience; they are appreciated best via wide-field binoculars.

- NGC 6709: An open cluster in Aquila; a compact, pleasing binocular and small-scope target.

- M71 (Sagitta): A compact globular cluster in the tiny constellation Sagitta, near the Triangle’s southern boundary. Medium magnifications begin to show its grainy texture.

- Cr 399 (Brocchi’s Cluster, the “Coathanger”): In Vulpecula, within the Triangle, a striking asterism that resembles a coat hanger in binoculars. Best viewed at low power.

Use the Observing Tips to match each object to your skies and equipment. Narrowband filters can transform views of emission nebulae, while magnification choices matter for planetary nebulae like M57.

Understanding the Milky Way Through the Triangle

One reason the Summer Triangle is a perennial favorite is that it serves as a living map of our galaxy’s structure. Every sweep of the eyepiece moves across star-forming regions, dust lanes, and fossil relics of stellar explosions.

The Great Rift and interstellar dust

Look carefully at the band of the Milky Way through Cygnus and Aquila: you will see a conspicuous split that traces a dark river through the starry light. This is the Great Rift, a series of overlapping dark nebulae composed of cold interstellar dust and gas that obscure the background star fields. These clouds are not empty; they are the raw material for star formation. Regions such as the North America Nebula and the Pelican Nebula near Deneb signal active stellar nurseries, their gas energized by young, hot stars.

Planetary nebulae and the late stages of stellar life

Near Vega, the Ring Nebula (M57) exemplifies a later phase of stellar evolution. Planetary nebulae form when Sun-like stars shed their outer layers, leaving a hot core that ionizes the ejected gas. Observing M57 at moderate to high power can reveal a brighter rim and a dimmer center. Compare this to the supernova remnant of the Veil Nebula in Cygnus—an older, more diffuse structure tracing a massive star’s explosive end. The contrast between these objects underlines the diversity of outcomes in stellar life cycles.

Attribution: NASA/JPL-Caltech

Open clusters and star formation

Open clusters like M39 and those around Sadr demonstrate the groupings of young stars that drift apart over time. In the Triangle region, many clusters are best seen at low magnification; wide-field binoculars or small, short focal length telescopes excel here. Objects listed in Deep-Sky Highlights offer a sampling across this evolutionary theme—from newly minted stellar associations to evolved remnants.

Observing Tips for Urban and Dark-Sky Viewers

Whether you observe from a rooftop in the city or a rural dark-sky site, the Summer Triangle caters to varied conditions. Below are strategies to maximize your session’s yield.

From light-polluted skies

- Prioritize bright, high-contrast targets: Double stars like Albireo and Epsilon Lyrae shine through urban glow. M57 is compact enough to punch through moderate light pollution at medium to high power.

- Use magnification strategically: Higher magnification darkens the background sky and can help with planetary nebulae and double stars. Avoid pushing power beyond what seeing allows.

- Observe when objects are highest: Timing your session for when targets transit the meridian reduces atmospheric extinction and turbulence.

- Filters for nebulae: Narrowband UHC and O III filters can boost contrast for emission nebulae even in suburban areas, though very bright city centers may still wash out diffuse targets.

From dark-sky sites

- Go wide-field first: Sweep from Deneb through Sadr into Aquila with 7×–10× binoculars. Note the textured glow of unresolved stars and the dark lanes of the Great Rift.

- Chase nebulosity with filters: For the Veil, North America, and Pelican, an O III or UHC filter on a short focal length scope can make filamentary structures and cloud edges pop.

- Revisit targets at varied magnifications: The Veil’s sweeping arcs are magical at 2–4 degrees true field, while M57 demands 100× or more to bring out the torus-like appearance.

- Log and sketch: Documenting fine details—brightness variations, faint extensions, subtle star color—sharpens your observing skills and makes return visits more rewarding.

Comfort, seeing, and transparency

- Cool your optics: Allow telescopes to thermally equilibrate. Tube currents soften views; a cooled mirror or lens improves contrast.

- Monitor seeing vs. transparency: Nebulae depend on transparency more than seeing; double stars and planetary nebulae benefit from steady seeing.

- Shield stray light: A simple shroud or dew shield can increase contrast. For binocular work, use a hooded jacket to block side light.

- Dew control: In humid summers, dew bands or shields are essential to keep optics clear.

Plan a route through the Triangle with the Star-Hopping notes and use the object list in Deep-Sky Highlights to match targets to your conditions.

Cultural Footprints and Asterisms Related to the Triangle

The Summer Triangle’s prominence in the northern sky has naturally lent it cultural resonance and practical value in skywatching. Although the Triangle itself is a modern popularization—featured in many 20th-century star guides—its component constellations have ancient roots:

- Lyra (Vega): Often associated with a lyre or harp in Greco-Roman tradition, with Vega as the harp’s jewel. Vega’s brilliance and near-zenith placement at mid-northern latitudes give it a starring role in many seasonal sky tours.

- Cygnus (Deneb): Depicted as a swan flying along the Milky Way in multiple cultural traditions. The Northern Cross is a prominent subset asterism that adapts well to modern navigation under the night sky.

- Aquila (Altair): Identified with an eagle. In various cultural contexts, the eagle’s position near the Milky Way underscores themes of flight and celestial passage.

Modern amateur astronomers use the Summer Triangle as a seasonal signpost—a quick orientation tool when scouting for the Milky Way, meteor showers, or satellite passes. It also pairs well with other asterisms:

- Northern Cross: Within the Triangle, the cross-shaped pattern of Cygnus frames Deneb and directs observers toward rich nebular regions.

- Coathanger (Cr 399): This binocular asterism in Vulpecula sits comfortably in the Triangle’s southern interior and is a crowd-pleaser at public star parties.

If you’re running a public outreach event, the Triangle provides an intuitive tour: begin with what the asterism is, hop through navigational cues, and then showcase a few spectacular objects from Deep-Sky Highlights. Its bright corner stars make it forgiving for new observers learning the sky for the first time.

Gear, Filters, and Planning Tools for the Triangle

Although the Summer Triangle rewards naked-eye observing, specific tools and practices can elevate your experience—especially for faint nebulae. This section complements the techniques in Observing Tips and the object list in Deep-Sky Highlights.

Optics: binoculars and telescopes

- Binoculars (7×–10×, 42–50 mm): Ideal for sweeping the Milky Way, framing large targets like the North America and Pelican nebulas, and appreciating dark nebulae contours. The Coathanger asterism is best at low power.

- Small refractors (60–100 mm): Excellent for wide-field views with a narrowband filter. Short focal length scopes excel at the Veil’s broad arcs.

- Medium reflectors (150–250 mm): Useful for teasing structure in planetary nebulae (e.g., M57), resolving open clusters, and improving visibility of faint nebulosity with filters.

Filters and eyepieces

- O III filter: A top choice for the Veil Nebula and many emission nebulae. It selectively transmits doubly ionized oxygen lines, dramatically lifting contrast against the sky background.

- UHC filter: A versatile narrowband option that works well across various emission nebulae, including the North America and Pelican complexes.

- Eyepiece strategy: Keep a wide-field eyepiece for finding, a medium-power eyepiece (60×–120×) for detail, and a higher-power eyepiece (150×+) for compact targets like M57 or double-star splits.

Planning and sky conditions

- Moon phase: Plan nebula-hunting sessions near new moon. Planetary nebulae and double stars tolerate moonlight better than diffuse objects.

- Transparency vs. seeing: If the air is exceptionally clear (good transparency), emphasize wide-field nebulae. If the air is steady (good seeing), push magnification on M57 and double stars.

- Charts and apps: Use printed atlases or planetarium apps to mark the positions of NGC 7000, IC 5070, the Veil, and clusters around Sadr. A pre-made list shortens time spent hunting in the field.

Frequently Asked Questions

Is the Summer Triangle visible from the Southern Hemisphere?

Yes, at many southern latitudes—particularly in the subtropics and mid-latitudes—you can see most or all of the Triangle low in the northern sky during the Southern Hemisphere’s winter evenings (June–August). However, as you travel farther south, Deneb drops lower and eventually becomes invisible; from far-southern locations, the full Triangle cannot be seen. For seasonal timing and latitude-specific notes, see When and Where to See the Summer Triangle.

Are Vega, Deneb, and Altair the brightest stars in the sky?

They are among the brightest but not the very brightest. Vega is one of the brightest stars visible from mid-northern latitudes and often catches the eye quickly at dusk. Altair is also bright, and Deneb is first-magnitude despite its great distance. However, Sirius (in Canis Major) and Arcturus (in Boötes), among others, outshine them. The Triangle’s fame comes from the convenient arrangement of three bright stars in a large, easily recognized pattern rather than from absolute brightness ranking.

Final Thoughts on Exploring the Summer Triangle

Attribution: Yejianfei

The Summer Triangle is both a beacon for casual stargazers and a deep reservoir of astronomical riches for seasoned observers. With Vega, Deneb, and Altair as anchors, you gain a reliable roadmap to the northern Milky Way: planetary nebulae like M57, sweeping supernova remnants like the Veil, rich star clouds around Sadr, and evocative dark nebulae like the “E”. From city rooftops, you can savor compact, high-contrast targets and doubles; from dark sites, the Triangle becomes a grand tour of nebular architecture and galactic structure.

Use the seasonality and latitude guidance in When and Where to See the Summer Triangle, hone your paths with Star-Hopping, and build a target list from Deep-Sky Highlights. With a modest pair of binoculars or a small telescope—and a bit of patience—this region will keep delivering new details and discoveries throughout the summer and well into autumn.

If you enjoyed this guide, consider following our ongoing series on the night sky. Subscribe to our newsletter for upcoming deep dives into constellations, seasonal observing projects, and equipment tips tailored to help you see more—no matter where you observe from.