Table of Contents

n

- n

- What Is Europa, Jupiter’s Ocean Moon?

- Orbital Dynamics and Tidal Heating That Power Europa

- Surface Geology and the Multi-layered Ice Shell

- Evidence for a Global Subsurface Ocean

- Chemistry, Energy Sources, and Habitability Potential

- Jovian Radiation Environment and Its Implications

- Plumes, Chaos Terrain, and Surface–Ocean Material Exchange

- Missions to Europa: From Galileo to JUICE and Europa Clipper

- Key Science Instruments and Priorities for Upcoming Flybys

- Landing Challenges and Concepts for Sampling Europa

- How Europa Compares to Enceladus, Ganymede, and Titan

- How to Observe Europa from Earth with Amateur Gear

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Datasets, Papers, and Further Reading for Europa Research

- Final Thoughts on Exploring Europa’s Ocean World

n

n

n

n

n

n

n

n

n

n

n

n

n

n

n

nn

What Is Europa, Jupiter’s Ocean Moon?

n

Europa is one of Jupiter’s four large Galilean moons, discovered by Galileo Galilei in 1610. Slightly smaller than Earth’s Moon, Europa spans roughly 3,121 kilometers in diameter and orbits Jupiter every 3.55 days. Its surface is a bright, water-ice shell scored by long, dark lineae and punctuated by disrupted “chaos” regions. Beneath that ice, strong geophysical evidence indicates a global, salty ocean—a prime target in the search for life beyond Earth.

n

n

nnn

What makes Europa scientifically compelling is the confluence of three factors:

n

- n

- A global subsurface ocean, evidenced by magnetometry and geologic activity.

- Tidal heating from Jupiter’s gravity, which can power ocean circulation and potentially hydrothermal activity at the seafloor.

- Possible surface–ocean exchange via fractures and plumes, allowing materials and energy to move between layers.

n

n

n

n

These ingredients are fundamental to habitability. Europa presents a natural laboratory where water, energy, and chemistry might combine to support microbial ecosystems. In the sections below, we synthesize what is known about Europa’s interior, surface processes, radiation environment, and the missions poised to answer the most consequential questions. For contextual links, see Evidence for a Global Subsurface Ocean and Plumes, Chaos Terrain, and Surface–Ocean Material Exchange.

nn

Orbital Dynamics and Tidal Heating That Power Europa

n

Europa’s interior energy budget is dominated by tidal dissipation—heat generated as the moon flexes under Jupiter’s powerful gravity. Europa orbits in a 1:2:4 Laplace resonance with Io and Ganymede: for every orbit of Ganymede, Europa completes two, and Io completes four. This configuration maintains Europa’s orbital eccentricity, ensuring ongoing flexing and internal frictional heating.

n

Key orbital and dynamical properties include:

n

- n

- Mean orbital distance: about 670,900 km from Jupiter, within the giant planet’s intense magnetosphere.

- Orbital period: roughly 3.55 Earth days; Europa is tidally locked, showing the same face to Jupiter.

- Eccentricity: small but nonzero; sufficient to drive flexing and heat production.

n

n

n

n

The physics is straightforward: as Europa travels along its slightly elliptical path, the varying gravitational pull squashes and stretches the moon. Internal friction converts a portion of this mechanical work into heat. This heat source can sustain a thick, liquid ocean beneath the ice shell even though surface temperatures hover around tens of kelvins. Tidal heating might also power hydrothermal vents at the ocean floor—particularly exciting from a biosignature standpoint, as vents on Earth host robust microbial ecosystems.

n

Importantly, tidal heating is not uniform. It depends on Europa’s internal structure (e.g., the thickness and rheology of the ice shell) and the distribution of materials in the moon’s mantle and core. Variations in heat flow can manifest at the surface, influencing the patterns of ridges, fractures, and chaos terrain discussed in Surface Geology and the Multi-layered Ice Shell.

n

n

Europa’s Laplace resonance with Io and Ganymede acts like a cosmic metronome, ensuring the gravitational “kneading” never stops—and the ocean stays liquid.

n

nn

Surface Geology and the Multi-layered Ice Shell

n

Europa’s surface reflects a history of stress, cracking, and resurfacing. The most conspicuous features are:

n

n

nnn

- n

- Lineae: long, often double-tracked stripes extending for hundreds to thousands of kilometers. They are interpreted as zones of fracturing and possible shear motion in the ice.

- Ridges and bands: regions where new ice may have been emplaced, analogous in spirit to seafloor spreading but scaled to an icy shell.

- Chaos terrain: jumbled patches composed of tilted blocks and hummocky material, suggesting partial melting, brine intrusion, or ice shell disruption.

- Low crater density: indicating a geologically young surface relative to the age of the Solar System.

n

n

n

n

n

Collectively, these morphologies point to an active or recently active exterior. The ice shell is commonly modeled as a multi-layered structure:

n

- n

- Cold, brittle lid: near-surface ice that behaves rigidly at Europa’s frigid temperatures.

- Warmer, ductile ice: deeper layers where ice can flow slowly under stress.

- Subsurface ocean: saline water underlying the ice; its thickness and salinity affect conductivity and thermal structure.

n

n

n

n

The thickness of the ice shell remains uncertain, with estimates ranging from several to a few tens of kilometers. Remote sensing—especially ice-penetrating radar aboard upcoming missions—aims to refine these constraints. Thickness variations likely modulate where the shell can fracture and how brines migrate, both of which relate to the potential for surface–ocean exchange discussed in Plumes, Chaos Terrain, and Surface–Ocean Material Exchange.

n

Europa’s coloration—predominantly bright ice with reddish-brown streaks—may result from irradiated salts and sulfur compounds delivered from Io or endogenous materials brought up from the interior. Spectroscopic studies have identified hydrated materials, with composition likely varying across regions. The combination of radiolytic processing at the surface and the presence of salts has key implications for Chemistry, Energy Sources, and Habitability Potential.

nn

Evidence for a Global Subsurface Ocean

n

Multiple independent observations converge on the conclusion that Europa harbors a global ocean beneath its ice. The strongest lines of evidence include:

n

- n

- Induced magnetism: Spacecraft measurements detected a magnetic signature consistent with an electrically conductive layer beneath the surface. A salty ocean would provide the necessary conductivity to respond to Jupiter’s rotating magnetic field and produce the observed induced field.

- Geological indicators: The presence of lineae, bands, and chaos terrain implies that liquid or ductile layers exist—or existed—near enough to the surface to allow large-scale rearrangement.

- Thermal models: Tidal dissipation and heat transport calculations favor conditions where an ocean persists over geologic timescales, rather than freezing solid.

n

n

n

n

These threads knit together into a coherent picture: Europa almost certainly hosts a global, saline ocean. The ocean’s depth may reach tens to over a hundred kilometers, with a total water volume that could exceed that of Earth’s oceans combined, depending on the exact structure of the ice and ocean layers. The salinity likely influences both the electrical properties (critical for magnetic sounding by flyby missions) and potential density stratification within the ocean.

n

The remaining questions are equally intriguing:

n

- n

- Is the ocean in contact with a rocky seafloor, enabling water–rock interactions and serpentinization chemistry?

- Are hydrothermal vents present, creating energy-rich gradients as on Earth’s mid-ocean ridges?

- How quickly do materials from the surface reach the ocean, and vice versa?

n

n

n

n

New gravity, radar, and magnetic field measurements will be essential to answering these questions, as outlined in Key Science Instruments and Priorities for Upcoming Flybys.

n

Chemistry, Energy Sources, and Habitability Potential

n

On Earth, life thrives where liquid water, chemical building blocks, and usable energy intersect. Europa plausibly offers all three, albeit in a cryptic, subsurface setting.

n

Essential ingredients

n

- n

- Water: A stable, global reservoir, protected from vacuum and extreme surface temperatures by the ice shell.

- Elements: Carbon, hydrogen, nitrogen, oxygen, phosphorus, and sulfur (CHNOPS) can be supplied via rock–water interactions and cometary/meteoritic delivery.

- Energy: Redox gradients may arise from radiolytic oxidants generated at the surface and reductants delivered from the interior, as well as from tidal and hydrothermal processes.

n

n

n

n

Surface radiolysis and oxidant delivery

n

Europa’s surface is bombarded by energetic particles trapped in Jupiter’s magnetosphere. These particles can break water molecules and other compounds, creating oxidants such as oxygen and hydrogen peroxide. If these species migrate downward—via fractures, brine percolation, or subduction-like processes—they could help sustain a chemical disequilibrium in the ocean that life could exploit. This “oxidant ladder” concept links Europa’s harsh radiation environment (see Jovian Radiation Environment and Its Implications) to subsurface habitability.

n

Hydrothermal energy at the seafloor

n

If Europa’s ocean sits atop a rocky mantle, tidal heating may drive hydrothermal circulation analogous to Earth’s black smokers. Such environments provide redox gradients and organic synthesis pathways even in the absence of sunlight. Laboratory and theoretical studies of water–rock reactions, including serpentinization, suggest plausible mechanisms for generating hydrogen and other potential energy sources for microbial metabolism.

n

Timescales and stability

n

Habitability also depends on time. If Europa’s ocean has persisted for hundreds of millions to billions of years, life would have more time to originate and adapt. Thermal modeling indicates that Europa’s ocean could be long-lived, though details depend on internal composition and heat flow. The surface appears geologically young, implying ongoing activity that might facilitate material exchange between the surface and the ocean.

n

While no direct evidence of life exists, Europa’s combination of liquid water, energy sources, and potentially bioavailable chemistry makes it one of the most promising targets for astrobiology in the Solar System.

nn

Jovian Radiation Environment and Its Implications

n

Europa orbits deep within Jupiter’s magnetosphere, where charged particles—electrons and ions—are accelerated to high energies. These particles bombard Europa’s surface, creating a radiation field that would be instantly hazardous to unshielded humans. Spacecraft are designed with robust shielding and careful flyby strategies to manage this environment.

n

Implications of this radiation include:

n

- n

- Surface chemistry: Radiolysis produces oxidants and alters the spectral signatures of surface materials, complicating the task of compositional mapping.

- Material weathering: Radiation can modify salts, organics, and ices, blurring the connection between current observations and original materials.

- Biological survivability: The surface is not a friendly environment for life. If life exists, it would likely be subsurface, shielded by meters to kilometers of ice.

- Mission design: Radiation doses drive choices about flyby altitudes, trajectories, instrument operation times, and electronics shielding.

n

n

n

n

n

Despite its challenges, radiation is not purely an obstacle. It also helps generate oxidants that could nurture subsurface life if transported inward, linking back to Chemistry, Energy Sources, and Habitability Potential. Understanding the radiation environment is, therefore, essential for both astrobiology and engineering.

nn

Plumes, Chaos Terrain, and Surface–Ocean Material Exchange

n

One of the most exciting possibilities is that Europa occasionally vents water vapor through plumes. If confirmed to be widespread and persistent, plumes could offer a way to sample subsurface materials—potentially even ocean-derived particles—without drilling through kilometers of ice.

n

Why plumes matter

n

- n

- Sampling opportunity: A spacecraft can fly through plume material, analyzing particles and gases for salts, organics, and isotopic ratios.

- Process insight: Plumes would indicate pathways connecting the ocean, warm ice, or shallow reservoirs to the surface.

- Temporal variability: Changes in plume activity could reveal how Europa responds to tidal stresses over its orbit.

n

n

n

n

Ground- and space-based observations have reported candidate plume detections, often using ultraviolet auroral emissions or absorption signatures during transits. Not all studies agree, and the frequency, strength, and source regions of plumes remain under active investigation. Whether plumes tap the deep ocean or only shallow briny pockets is also unknown.

n

Chaos terrain and brine migration

n

Chaos terrains—regions of disrupted, blocky ice—may result from partial melting or convective overturn. Proposed mechanisms include intrusion of warm, saline water into the base of the brittle lid and refreezing that buoyantly rearranges surface blocks. These processes could concentrate salts and organics near the surface, enhancing the science return of flyby observations highlighted in Key Science Instruments and Priorities for Upcoming Flybys.

n

n

nnn

Material cycling might work both ways: oxidants generated at the surface could be delivered downward, while interior brines carrying reduced species could move upward. The efficiency and geometry of this exchange remain crucial unknowns for assessing Europa’s habitability.

nn

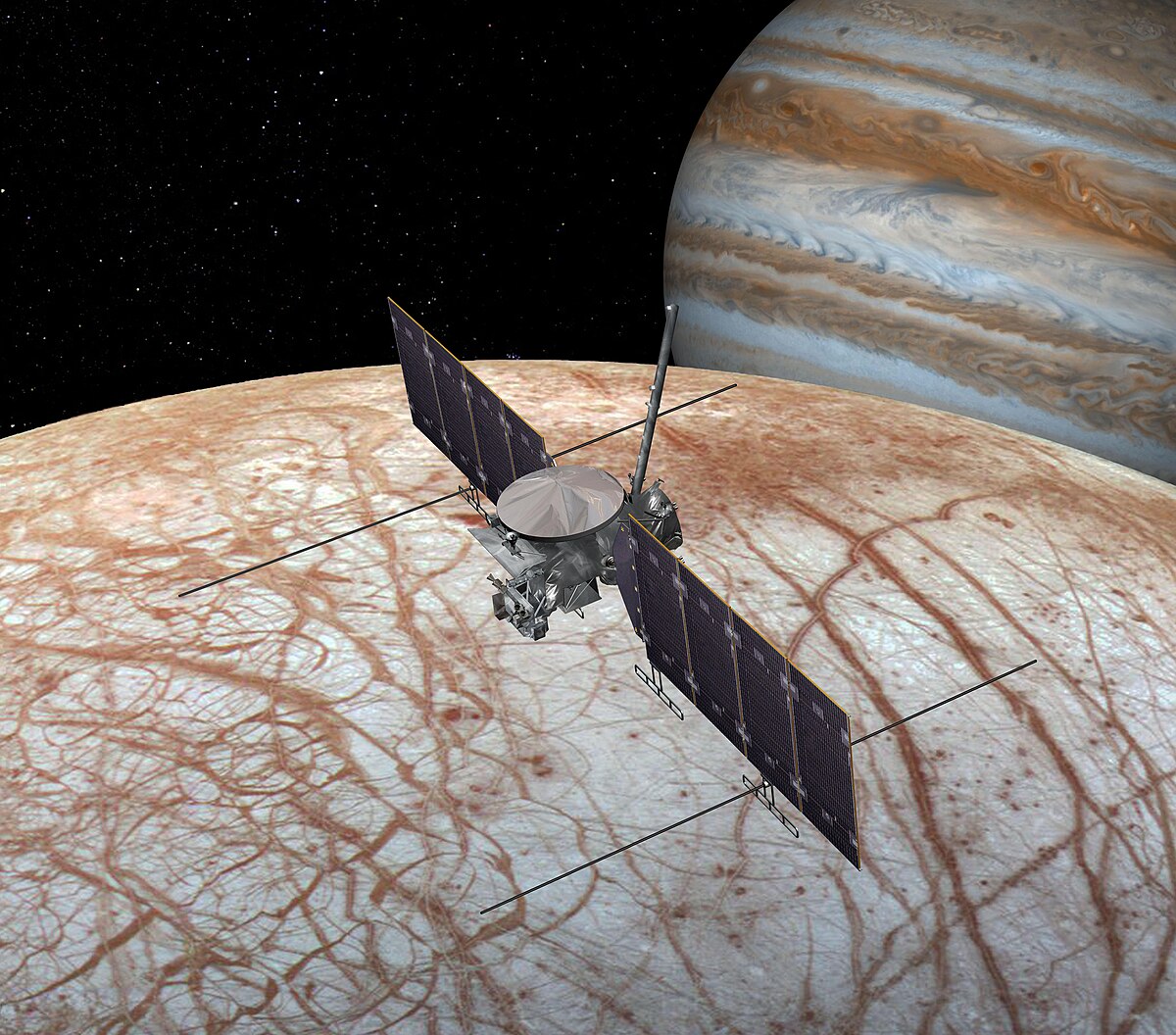

Missions to Europa: From Galileo to JUICE and Europa Clipper

n

Europa has been observed by multiple spacecraft, each contributing differently to our understanding:

n

- n

- Voyager flybys: First close-up images revealed a smooth, bright, ice-covered world with striking linear features.

- Galileo orbiter: Operating in the 1990s and early 2000s, Galileo revolutionized Europa science. Magnetometer data supported an induced magnetic field consistent with a salty ocean. Imaging and spectral data characterized lineae, chaos terrains, and compositional heterogeneity.

- Hubble Space Telescope: Ultraviolet observations reported candidate plume signatures and characterized the tenuous atmosphere.

- Juno mission flyby: A close pass provided fresh imagery and context on surface morphology and environment.

n

n

n

n

n

Two major missions are set to transform Europa studies in the coming decade:

n

n

nnn

- n

- ESA’s JUICE (Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer): Launched in 2023, JUICE will explore the Jovian system with a focus on Ganymede, but it is planned to conduct flybys of Europa and Callisto. Its instrument suite will enable remote sensing of composition, magnetic fields, and plasma interactions, contributing to Europa’s global context.

- NASA’s Europa Clipper: Planned for extensive flybys of Europa, Europa Clipper is designed to traverse multiple longitudes and local times, building a global map of surface composition, thermal anomalies, interior structure, and potential plume activity. Its orbit around Jupiter will allow repeated passes that sample a wide range of conditions.

n

n

n

Europa Clipper’s science plan is organized around determining the habitability of Europa’s ocean and ice shell. Together with JUICE, these missions will provide complementary views of Europa’s environment, from wide-angle system context to high-detail regional investigations. For instrument-level details, jump to Key Science Instruments and Priorities for Upcoming Flybys.

nn

Key Science Instruments and Priorities for Upcoming Flybys

n

Probing an ocean beneath an icy shell requires a diverse instrument toolkit. While the specific acronyms and designs vary by mission, the principal capabilities include:

n

n

nnn

- n

- Ice-penetrating radar: Sends radio pulses into the ice to detect layering, embedded water pockets, and the depth to the ocean where feasible. These data constrain ice thickness and the distribution of brines—crucial for understanding ice-shell structure and potential exchange pathways.

- Magnetometers: Measures Jupiter’s field and Europa’s induced response to infer the conductivity, depth, and possibly the salinity of the subsurface ocean.

- Thermal mapping: Infrared instruments search for warm spots—localized heat anomalies that may indicate recent activity, thin ice, or plume source regions.

- Imaging systems: Visible and near-infrared cameras capture high-resolution context for lineae, ridges, and chaos terrains; stereo imaging informs topography and geological history.

- Mass spectrometers: Analyze neutral gases and ions in the exosphere or plume material to identify water vapor, organics, and trace species.

- Dust analyzers: Characterize ice and mineral grains lofted from the surface, with composition giving clues to subsurface reservoirs.

- Plasma and particles instruments: Map the electromagnetic environment and measure how Europa interacts with Jupiter’s magnetosphere.

- Gravity/radio science: Track subtle shifts in spacecraft motion to infer Europa’s internal mass distribution and potential tidal response.

n

n

n

n

n

n

n

n

n

Priority science questions targeted by these tools include:

n

- n

- Ocean properties: What are the depth, salinity, and thickness of the ice shell above it? Do radar reflections indicate water pockets within the shell?

- Active processes: Are there plumes, thermally anomalous hotspots, or changing surface features that betray ongoing activity?

- Composition: What salts, organics, and hydrates are present at the surface, and how do they vary spatially? Are there regions where radiolysis has preserved unique signatures?

- Habitability metrics: Can oxidants from the surface reach the ocean? Are there signs pointing to hydrothermal activity at the seafloor?

n

n

n

n

n

The synergy is key: magnetometry constrains ocean conductivity; radar probes ice structure; mass spectrometry and dust analysis sample materials directly; imaging and thermal mapping provide geologic and activity context. Together, they address the core objective articulated in Chemistry, Energy Sources, and Habitability Potential.

nn

Landing Challenges and Concepts for Sampling Europa

n

While current flagship strategies emphasize flybys, the allure of a lander or penetrator remains strong. Sampling the surface—and ideally freshly exposed or erupted material—could provide definitive chemical context for habitability, including the presence of complex organics.

n

Key engineering challenges

n

- n

- Radiation shielding: Surface radiation can rapidly degrade electronics, dictating short mission lifetimes or substantial shielding mass.

- Terrain hazards: Ridges, troughs, and uneven blocky chaos terrain complicate landing and mobility.

- Planetary protection: Sterilization standards must be stringent to prevent forward contamination of a potentially habitable environment.

- Communications: A relay via an orbiter or flyby platform may be necessary to handle line-of-sight constraints.

n

n

n

n

n

Sampling strategies

n

- n

- Touch-and-go: Brief contact to collect surface material, minimizing radiation exposure.

- Shallow drilling or scraping: Accessing material centimeters to decimeters below the surface may reduce radiation-processed layers.

- Plume flythrough sampling: If active plumes are present, an orbiter can analyze emitted particles and gases, providing a virtual sample of subsurface reservoirs.

n

n

n

n

Until landing challenges are resolved, flyby missions can still address central questions about habitability and search for accessible targets. A smart pathway combines reconnaissance—mapping safe, scientifically rich sites—with technology maturation for next-generation landers.

nn

How Europa Compares to Enceladus, Ganymede, and Titan

n

Europa is not the Solar System’s only ocean world. Comparing Europa with its neighbors clarifies different pathways to habitability:

n

- n

- Enceladus (Saturn): This small moon has active jets that vent water vapor and icy grains from a subsurface ocean through “tiger stripe” fractures. The plumes offer direct access to ocean chemistry, including salts and organics detected by past flybys. Enceladus’s smaller size and different tidal environment contrast with Europa’s thicker shell and stronger radiation exposure.

- Ganymede (Jupiter): Larger than Mercury, Ganymede likely hosts a deep interior ocean sandwiched between ice layers. It possesses a unique intrinsic magnetic field, unlike Europa. Habitability questions for Ganymede center on whether its ocean contacts rock, a key difference from Europa where ocean–rock contact is considered more likely.

- Titan (Saturn): Titan has surface lakes and seas of hydrocarbons, thick nitrogen-rich atmosphere, and a probable interior ocean. Chemistry on Titan’s surface is fundamentally different (non-aqueous), though its interior could host water–ammonia mixtures.

n

n

n

n

These comparisons highlight Europa’s distinct strengths as an astrobiology target: an ocean likely in contact with rock, a vigorous tidal power source, and possible pathways for material exchange. On the other hand, Europa’s harsh radiation and challenging surface hamper exploration relative to Enceladus’s convenient plumes. Both worlds merit sustained, complementary study, as discussed in Missions to Europa.

nn

How to Observe Europa from Earth with Amateur Gear

n

n

nnn

Despite its scientific mystique, Europa is within reach of amateur observers. With a small telescope, you can watch the Galilean moons change position from night to night—and sometimes from hour to hour.

n

When and how to see Europa

n

- n

- Telescopes: Even a 60–90 mm refractor under steady seeing will show Europa as a starlike point near Jupiter. A 150–200 mm reflector or SCT begins to resolve transits and shadows under excellent conditions.

- Transits and eclipses: Europa occasionally passes in front of or behind Jupiter as seen from Earth. During a transit, careful observers may detect the dark shadow of Europa on Jupiter’s cloud tops.

- Timing: Use reputable ephemeris tools or planetarium software to plan sessions when Europa is well separated from Jupiter or during shadow transits.

n

n

n

n

Astrophotography tips

n

- n

- Short exposures, high frame rates: For planetary imaging, capture thousands of frames and stack the best 5–20% to beat seeing.

- Filters: Red or IR-pass filters can sharpen details in poor seeing; Europa will remain a point, but Jupiter’s features and shadows improve.

- Annotation: Label Europa in your images and compare its position with predictions; over several nights you can trace its orbit visually.

n

n

n

n

While no amateur telescope can reveal Europa’s lineae or chaos terrain, visual tracking helps build intuition about orbital mechanics and lays a personal foundation for the deep-dive science in Orbital Dynamics and Tidal Heating.

nn

Frequently Asked Questions

n

Does Europa definitely have an ocean?

n

Multiple lines of evidence—especially the detection of an induced magnetic field consistent with a conductive, salty layer—strongly support a global subsurface ocean. Geological features and thermal modeling align with this picture. While no instrument has directly “seen” the ocean, the convergence of data makes it the most robust interpretation.

n

Could life exist on Europa today?

n

It’s plausible. Europa appears to have liquid water, energy sources (tidal heating, possible hydrothermal activity), and potentially nutrient cycling between surface and interior. The key unknowns are the efficiency of material exchange, the persistence of the ocean, and the availability of usable redox gradients. Upcoming missions aim to assess these habitability factors, as described in Key Science Instruments and Priorities for Upcoming Flybys.

nn

Datasets, Papers, and Further Reading for Europa Research

n

If you want to explore the technical literature and data archives, consider the following avenues:

n

- n

- Planetary data systems: Public archives host calibrated data from past missions, including imaging, spectra, and magnetometer measurements relevant to ocean evidence and surface geology.

- Peer-reviewed journals: Look for articles on Europa’s magnetism, ice mechanics, plume searches, and astrobiology assessments in major planetary science journals.

- Mission documentation: Overviews and technical papers describe anticipated performance of radar, magnetometers, mass spectrometers, and imaging systems for JUICE and Europa Clipper.

- Conference proceedings: Presentations often include the latest results, such as refined plume detections, compositional maps, or updated models of tidal heating.

n

n

n

n

n

As data arrive from new flybys, revisit these resources to track evolving interpretations—particularly about ice thickness variability, plume confirmation, and ocean salinity.

nn

Final Thoughts on Exploring Europa’s Ocean World

n

Europa stands at the intersection of geology, oceanography, and astrobiology. The case for a global saltwater ocean is strong. Tidal forces provide a steady power source, while surface radiolysis may generate oxidants that, if delivered inward, sustain chemical disequilibria favorable to life. The icy crust displays fractures, bands, and chaos terrains that record a dynamic history—potentially including pathways that shuttle materials between surface and interior.

n

Upcoming spacecraft will not directly detect life, but they will rigorously test Europa’s habitability: mapping ice shell structure, gauging ocean properties via magnetic and gravity fields, searching for thermal and plume activity, and inventorying surface composition. These measurements will pull Europa from the realm of informed speculation into a data-rich era where we can evaluate core questions with precision.

n

For observers and enthusiasts, Europa offers both inspiration and participation. Watch the moon’s nightly dance around Jupiter through a small telescope. Follow mission updates, explore open datasets, and read the latest analyses. Most importantly, stay engaged: subscribe to our newsletter for future deep dives into ocean worlds, planetary habitability, and the discoveries that await in the Jovian system.