Table of Contents

- What Are Cosmic Rays in Astrophysics?

- Where Do Cosmic Rays Come From? Supernova Remnants to Active Galaxies

- The Cosmic-Ray Energy Spectrum: From GeV to 10^20 eV

- How Cosmic Rays Propagate Through the Galaxy

- When Particles Hit: Atmospheric Air Showers and Secondaries

- How We Detect Cosmic Rays: Spacecraft, Balloons, and Ground Arrays

- Radiation Impacts: Aviation, Spaceflight, and Electronics

- Do Cosmic Rays Affect Climate? Evidence and Limits

- What Recent Experiments Reveal About Composition and Anisotropy

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Final Thoughts on Understanding Cosmic Rays

What Are Cosmic Rays in Astrophysics?

Cosmic rays are high-energy particles—mostly protons, with a significant minority of helium nuclei and trace amounts of heavier nuclei and electrons—that travel through space at nearly the speed of light. When these particles reach Earth, they collide with atoms in the upper atmosphere and initiate cascades of secondary particles, a phenomenon that reveals their presence even if we never see the original primary particle directly.

Discovered in the early twentieth century through high-altitude balloon experiments, cosmic rays have since become a key probe of high-energy processes in the Universe. Their energies span an extraordinary range—from millions of electron volts (MeV) to more than 1020 electron volts (eV) for so-called ultra-high-energy cosmic rays (UHECRs). For context, the most energetic cosmic rays detected carry about as much kinetic energy as a fast-pitched baseball, concentrated in a single subatomic particle.

Astrophysicists classify cosmic rays into categories based on energy and composition:

- Galactic cosmic rays (GCRs): Thought to originate primarily within our Milky Way, these dominate the flux at energies up to around the “knee” in the spectrum (see energy spectrum).

- Extragalactic cosmic rays (EGCRs): At the highest energies, sources outside our Galaxy are suspected, given the difficulties confining such particles within the Milky Way’s magnetic field.

- Solar energetic particles (SEPs): High-energy particles emitted by the Sun during solar flares and coronal mass ejections. SEPs are lower in energy than UHECRs but are important for radiation impacts on aviation and spaceflight.

Because cosmic rays are electrically charged, their paths bend in magnetic fields—both interstellar and interplanetary—obscuring their point of origin when they finally reach us. Consequently, we infer their sources via indirect evidence: gamma-ray signatures of particle interactions in candidate sources, secondary-to-primary composition ratios, and large-scale anisotropies at the highest energies. We will explore these lines of evidence throughout this article, including how cosmic rays are accelerated, how they propagate through the Galaxy, and how experiments on the ground and in space detect them.

Where Do Cosmic Rays Come From? Supernova Remnants to Active Galaxies

Identifying cosmic-ray sources is a central problem in high-energy astrophysics. Evidence points to a variety of accelerators across different energy ranges, with multiple mechanisms likely contributing. Here are the leading candidates and the reasoning behind them:

Supernova Remnants and Diffusive Shock Acceleration

The shock waves produced by exploding stars—supernova remnants (SNRs)—are widely regarded as prime accelerators of galactic cosmic rays up to at least the “knee” (around a few peta-electron volts, PeV). In the widely studied diffusive shock acceleration scenario, charged particles bounce back and forth across a shock front due to magnetic turbulence, gaining energy with each crossing. This produces a power-law energy distribution that resembles the observed cosmic-ray spectrum at lower energies.

Observations strengthen this picture. Gamma-ray telescopes have detected emissions from several SNRs consistent with the decay of neutral pions created when high-energy protons interact with surrounding gas. These “pion bump” signatures are considered evidence for hadronic cosmic-ray acceleration in at least some remnants. SNRs also inject heavy nuclei into the cosmic-ray population, as suggested by composition measurements.

Pulsar Wind Nebulae and Young Pulsars

Pulsars—rapidly spinning, magnetized neutron stars—can accelerate electrons and positrons within their magnetospheres and surrounding nebulae. Pulsar wind nebulae (PWNe) are especially efficient at accelerating leptons (electrons and positrons) to high energies. While they are likely major contributors to the local high-energy electron and positron populations, pulsars alone cannot easily account for the full spectrum of hadronic cosmic rays, which are predominantly protons and heavier nuclei.

Active Galactic Nuclei, Jets, and Radio Lobes

At the ultra-high-energy end, sources beyond our Galaxy become plausible. Active galactic nuclei (AGN)—supermassive black holes accreting matter and launching relativistic jets—are natural laboratories for particle acceleration. Shock waves and magnetic reconnection within jets and lobes can energize particles to extreme energies. While AGN are promising UHECR accelerators, their exact role is still an active research area, explored via correlations between observed UHECR arrival directions and large-scale structure.

Gamma-Ray Bursts, Starburst Galaxies, and Other Candidates

Other proposed sources for the highest-energy cosmic rays include gamma-ray bursts (GRBs) and starburst galaxies with elevated supernova rates. Both provide environments with intense shocks and magnetic fields. The contribution of each source class likely varies with energy, and it is plausible that the observed cosmic-ray population is a superposition of multiple accelerators operating across the cosmos.

At lower energies, the Sun itself can inject bursts of energetic particles into the heliosphere during solar storms. These solar energetic particles can lead to elevated radiation levels near Earth and are a key aspect of space weather and radiation exposure.

The Cosmic-Ray Energy Spectrum: From GeV to 10^20 eV

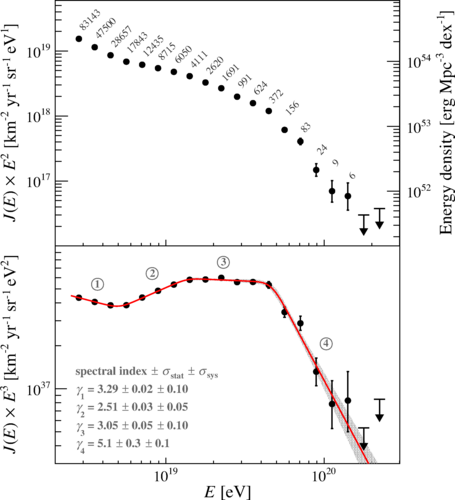

A defining feature of cosmic rays is their energy spectrum—the number of particles per energy interval. Over many orders of magnitude, the spectrum roughly follows a power law, with fewer and fewer particles at higher energies. Yet the spectrum is not a simple straight line on a log-log plot; it shows characteristic features that provide clues to acceleration and propagation mechanisms.

Key Landmarks: The Knee, Second Knee, and Ankle

- The knee: Around a few peta-electron volts (PeV), the spectrum steepens. This is often interpreted as a limit to the energy that typical Galactic sources—such as SNRs—can impart to charged particles, with heavier nuclei possibly extending to higher energies due to rigidity-dependent acceleration.

- The second knee: At energies above the knee, the spectrum shows additional structure, sometimes called the “second knee,” likely reflecting changes in composition and propagation effects.

- The ankle: Around a few exa-electron volts (EeV), the spectrum appears to flatten slightly. This “ankle” is often discussed in the context of a transition from Galactic to extragalactic cosmic rays.

At the highest energies—tens of EeV and above—the flux is extraordinarily low (a few particles per square kilometer per century at the very top end). Observatories must instrument vast areas and use indirect detection techniques to measure these rare events. The observed suppression in the flux at ultra-high energies is consistent with energy losses during propagation or the maximum energies of their sources.

What the Spectrum Suggests About Origins

The spectral steepening at the knee has long been associated with the limits of Galactic acceleration and with magnetic confinement. If the Milky Way’s magnetic field can no longer efficiently confine particles above certain rigidities, they escape more readily, depleting the local flux. Conversely, the ankle’s flattening hints that more distant extragalactic accelerators may dominate at higher energies. Combined with composition measurements, these features are key to disentangling the cosmic-ray origin story.

Precision measurements by space missions and ground arrays have also revealed spectral hardenings at lower rigidities for specific species (for example, protons and helium exhibiting breaks near a few hundred GV of rigidity), pointing to complex acceleration and transport processes. These details underscore why the spectrum is more than a simple power law: it is a history book encoded in particle energies.

How Cosmic Rays Propagate Through the Galaxy

After acceleration, cosmic rays do not travel to us along straight lines. Galactic magnetic fields, intertwined with turbulence, scatter charged particles and make their paths diffusive. This behavior shapes what we observe on Earth, from their energy spectrum to the slight anisotropies in arrival directions.

Diffusion, Confinement, and Escape

The Milky Way’s magnetic field and its turbulent fluctuations make cosmic-ray propagation akin to a random walk. The time cosmic rays spend in the Galactic halo depends on energy (or more precisely, rigidity, which is momentum per unit charge). Lower-rigidity particles are more easily confined and scatter more, while higher-rigidity particles escape more readily. Measurements of the ratios of secondary nuclei (created by spallation in the interstellar medium) to primary nuclei—such as boron-to-carbon (B/C)—constrain the average path lengths and confinement times.

These secondary-to-primary ratios encode how long cosmic rays have been cruising through the interstellar medium, colliding with gas and producing lighter fragments. Observationally, they indicate that cosmic rays spend considerable time in the Galaxy before escaping, but that this residence time decreases with energy. This dynamic links directly to features discussed in the energy spectrum, especially the knee.

Solar Modulation and the Heliosphere

Closer to home, the Sun and its magnetic field influence cosmic rays before they reach Earth. The solar wind, carrying the heliospheric magnetic field outward, modulates lower-energy cosmic rays (typically below a few GeV). During periods of high solar activity, the enhanced magnetic turbulence suppresses the flux of low-energy galactic cosmic rays at Earth. Conversely, during solar minima, more galactic cosmic rays penetrate the heliosphere, increasing the count rates measured by neutron monitors and spacecraft detectors.

Direct measurements both inside and beyond the heliosphere have deepened our understanding of modulation and interstellar space. Long-duration missions have provided complementary perspectives on the spectrum inside the heliosphere and, at great distances, on the local interstellar spectrum.

Small Anisotropies and Large-Scale Structure

Even with strong scattering, small but measurable anisotropies in the arrival directions of cosmic rays have been detected at certain energies. These may reflect gradients in the cosmic-ray density or nearby sources and are an active research area. At ultra-high energies, where magnetic deflections are smaller, large-scale dipole patterns have been reported, potentially tracing the distribution of extragalactic sources or the influence of extragalactic magnetic fields.

In summary, propagation is not a passive process; it shapes the observed spectrum, modifies the composition with energy, and filters what reaches us through the Sun’s variable magnetic environment.

When Particles Hit: Atmospheric Air Showers and Secondaries

Most cosmic rays never reach the ground as primaries. Instead, they collide with atoms in the upper atmosphere—primarily nitrogen and oxygen—and initiate a cascade of particles known as an extensive air shower.

Hadronic and Electromagnetic Cascades

The first interaction typically produces a spray of pions (π+, π−, π0) and other hadrons. Neutral pions decay almost immediately into gamma rays, which trigger electromagnetic sub-showers via pair production and bremsstrahlung. Charged pions decay into muons and neutrinos; muons, thanks to relativistic time dilation, can survive to reach ground level or even penetrate underground, where they are detectable. The result is a rapidly multiplying shower of particles spreading over large areas by the time it reaches the surface.

Key components of a typical air shower include:

- Electrons and positrons in electromagnetic cascades initiated by gamma rays from neutral pions.

- Muons, products of charged pion decays, which often reach the ground.

- Neutrinos, which almost never interact and sail through the Earth.

- Hadronic core, containing nucleons and charged mesons continuing hadronic interactions deeper into the atmosphere.

The spatial distribution of these particles and the timing of their arrival carry information about the energy and mass of the primary cosmic ray. Experiments exploit these signatures with arrays of surface detectors and telescopes that view the faint ultraviolet fluorescence of atmospheric nitrogen excited by the shower.

Geomagnetic Effects and Atmospheric Depth

Earth’s magnetic field deflects low-energy charged primaries and influences the lateral spread of some shower components. The density and depth of the atmosphere set the stage for where and how showers develop: higher-altitude observatories are closer to the shower maximum, while sea-level detectors observe more evolved cascades. These considerations drive the layout and elevation choices of major ground-based facilities that study cosmic-ray air showers, discussed in detection techniques.

How We Detect Cosmic Rays: Spacecraft, Balloons, and Ground Arrays

Cosmic rays are not observed with a single tool or method. Because their energies and fluxes span so widely, a diverse toolkit has been assembled—from spectrometers aboard the International Space Station to sprawling surface arrays covering thousands of square kilometers. Each technique trades precision, energy reach, exposure, and composition sensitivity in different ways.

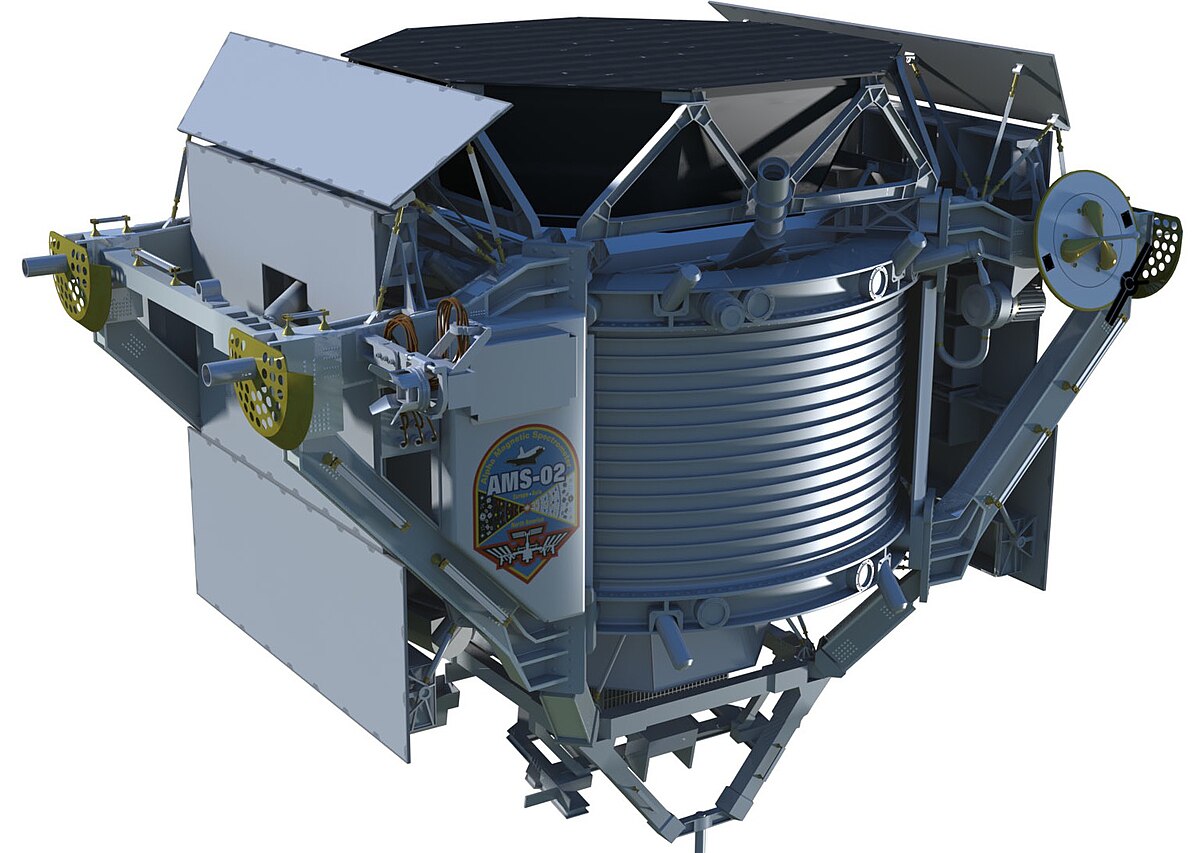

Space-Based Detectors

In space, instruments can directly measure the charge, energy, and trajectory of individual particles without the confounding influence of the atmosphere. Several notable missions have advanced our understanding of cosmic-ray composition and spectra:

- Magnetic spectrometers aboard satellites or the ISS use magnetic fields to bend particle trajectories, determining rigidity and, combined with velocity measurements, identifying species and energy.

- Calorimeters measure particle energy by absorbing the particle and recording the development of a shower within the detector.

- Transition radiation detectors and time-of-flight systems contribute to particle identification across broad energy ranges.

Space-based experiments have reported detailed fluxes of protons, helium, heavier nuclei, electrons, positrons, and antiprotons. Spectral features, such as hardenings at a few hundred GV rigidity for certain species, and the behavior of the positron fraction at high energies, have become important benchmarks for models of Galactic acceleration and propagation.

Balloon-Borne Experiments

High-altitude balloons provide a cost-effective platform for direct detection above most of the atmosphere. Long-duration balloon flights over polar regions can carry heavy payloads, yielding significant exposures for studies of rare heavy nuclei and detailed composition. Balloon experiments have measured isotope ratios, elemental abundances up to high atomic numbers, and energy spectra extending into the TeV range per nucleon, complementing space missions.

Ground-Based Observatories

At energies beyond the reach of direct detection, ground arrays and optical telescopes observe air showers. Two main approaches stand out:

- Surface detector arrays: Networks of particle detectors (often water-Cherenkov tanks or scintillators) sample the shower front as it spreads across large areas. Timing and signal amplitudes reconstruct the primary particle’s energy and direction.

- Fluorescence telescopes: Sensitive optical telescopes view the atmosphere on dark, clear nights to measure the ultraviolet glow from nitrogen excited by shower particles. This calorimetric view provides near-direct energy estimates and insights into the depth of shower maximum (Xmax), a key composition tracer.

Many major observatories combine both approaches in a “hybrid” configuration, improving energy calibration and composition sensitivity. Radio detection of air showers has also emerged as a powerful technique, with arrays measuring coherent radio emission generated by the geomagnetic deflection of shower electrons and positrons.

While gamma-ray telescopes using atmospheric Cherenkov techniques primarily target astrophysical gamma rays, they also observe cosmic-ray backgrounds and contribute to understanding shower physics and hadronic interaction models. Air-shower instruments optimized for gamma rays can still report valuable cosmic-ray measurements, including composition-sensitive parameters and anisotropy studies.

Cross-calibration across methods is essential. Surface arrays provide continuous duty cycle but are model-dependent for composition, while fluorescence telescopes offer calorimetry at the cost of limited operating time. Together, they build a coherent picture of the highest-energy cosmic rays and their arrival directions.

Radiation Impacts: Aviation, Spaceflight, and Electronics

Cosmic rays are not merely an astrophysical curiosity; they have tangible effects on technology and human activities. Their secondary particles contribute to radiation exposure at flight altitudes, influence the design and operation of spacecraft, and can induce errors in electronics. Understanding these impacts helps manage risk in aviation and space operations.

Radiation Exposure at Aviation Altitudes

At cruising altitudes for commercial aircraft, the atmosphere is thinner and provides less shielding from cosmic radiation. The result is elevated dose rates compared to sea level. Flight route, altitude, latitude, and the phase of the solar cycle all play roles:

- Latitude: Polar routes experience higher cosmic-ray fluxes due to geomagnetic cutoffs being lower near the poles.

- Altitude: Higher altitudes mean less shielding and higher dose rates.

- Solar activity: During solar maxima, enhanced solar modulation suppresses low-energy galactic cosmic rays, generally reducing dose rates; during minima, the opposite occurs. However, solar energetic particle events can cause short-term spikes.

Airline crew and frequent flyers receive higher annual doses than most people at sea level, though typical values remain within regulated occupational limits. Aviation authorities and space-weather services monitor radiation conditions, and airlines can reroute or adjust altitudes during significant solar events. For everyday flights, cosmic-ray exposure is a known and managed aspect of aviation safety.

Spaceflight and Mission Design

Beyond the protective blanket of Earth’s atmosphere, cosmic radiation becomes a dominant concern. Spacecraft face a combination of galactic cosmic rays, solar energetic particles, and trapped radiation belts. Mission designers employ multiple strategies to mitigate risk:

- Shielding: Structural materials and dedicated shielding reduce absorbed dose, though high-energy particles can generate secondary radiation. Shielding design balances mass constraints against protection needs.

- Mission timing: Some missions plan sensitive phases to avoid periods of heightened solar activity, when feasible, or incorporate storm shelters for crewed missions.

- Radiation-hardened electronics: Components are selected or engineered to withstand particle strikes and cumulative dose effects.

- Monitoring and forecasting: Onboard dosimeters and ground-based space weather forecasting support operational decisions.

For long-duration human exploration beyond low Earth orbit, galactic cosmic rays are a significant challenge due to their persistent presence and high energies. Ongoing research explores optimized shielding, pharmacological countermeasures, and habitat designs to reduce astronaut risk.

Single-Event Effects in Electronics

Even at ground level, cosmic-ray secondaries—especially neutrons and muons—can cause single-event effects (SEEs) in microelectronics. A single particle strike can flip a bit in memory (a single-event upset), induce transient currents, or cause more severe latch-up in sensitive circuits. As transistor sizes shrink and operating voltages drop, susceptibility to SEEs can increase.

Mitigations include error-correcting codes (ECC) in memory, redundancy, hardened designs, and shielding where practical. Data centers operating at higher elevations can see higher soft error rates due to increased secondary flux. Semiconductor reliability engineering routinely accounts for this “cosmic-ray background” in fault-tolerant system design.

Atmospheric Chemistry and Secondary Effects

Cosmic-ray induced ionization produces reactive species such as NOx in the upper atmosphere and contributes to background ionization that can influence processes like thunderstorm electrification. These effects are areas of ongoing research and are part of the broader picture connecting air-shower physics to terrestrial phenomena.

Do Cosmic Rays Affect Climate? Evidence and Limits

The idea that variations in cosmic-ray flux could influence Earth’s climate has intrigued scientists for decades. The proposed mechanism typically involves ion-induced nucleation: cosmic-ray ionization helps seed aerosol particles, which, under the right chemical conditions, can grow into cloud condensation nuclei (CCN), potentially affecting cloud cover and albedo.

Ion-Induced Nucleation and Laboratory Insights

Laboratory experiments have shown that ionization can enhance the formation of ultra-fine particles under certain conditions, especially in the presence of specific vapors like sulfuric acid, ammonia, and organic compounds. However, for these particles to affect cloud properties, they must grow to sizes where they can act as CCN, and the ambient atmosphere must support such growth. Laboratory findings place constraints on the plausibility of large climate effects from ionization alone.

Observations and Attribution Challenges

Separating the climate influence of cosmic rays from other factors—solar irradiance, volcanic aerosols, greenhouse gases, internal variability—is challenging. Some studies report correlations between cosmic-ray proxies and cloud cover over limited periods or regions, while others find weak or no robust correlations. Overall, the balance of evidence indicates that cosmic rays are a secondary factor compared with dominant drivers of modern climate change.

It is important to distinguish between short-term space weather impacts—such as transient atmospheric ionization pulses during solar particle events—and long-term climate trends. The latter are governed by a complex interplay of forcings, with cosmic-ray variations playing, at most, a modest role in the contemporary climate system.

Research continues, especially on microphysical pathways of aerosol growth in real atmospheric conditions. The emerging consensus is that while cosmic rays can influence nucleation under specific conditions, translating that into significant, widespread cloud or climate impacts is not strongly supported by the current body of evidence.

What Recent Experiments Reveal About Composition and Anisotropy

Modern experiments have profoundly sharpened the picture of cosmic-ray composition, spectral features, and arrival directions. By combining direct and indirect methods, researchers have mapped detailed spectra for many species and explored how composition evolves with energy. Highlights include:

Precision Composition and Spectra at GeV–TeV Energies

Space-based detectors have measured fluxes of protons, helium, and heavier nuclei with high precision, revealing spectral hardenings around a few hundred GV rigidity for some species. Electrons and positrons have been measured up to the TeV scale, with the positron fraction rising with energy before leveling off—a behavior that sparked considerable interest in astrophysical sources (such as pulsars) and particle-physics interpretations. Antiproton measurements have provided important constraints on propagation models and secondary production in the interstellar medium.

Balloon missions have complemented these findings with isotope ratios (e.g., beryllium and boron isotopes) that further refine models of propagation and cosmic-ray age. The combination of isotope data and elemental spectra tightens constraints on how diffusion, convection, and reacceleration might operate in the Milky Way.

Shower Depth and Composition at Ultra-High Energies

At EeV energies and above, ground-based observatories infer composition from the distribution of the depth of shower maximum (Xmax) and the muon content of showers. Trends in Xmax versus energy point to changes in the average mass of primaries, with indications that composition may become heavier over certain energy ranges. These interpretations are conditioned on hadronic interaction models extrapolated beyond accelerator energies, making cross-checks across observatories and models essential.

Notably, the highest-energy data show a suppression in the flux consistent with energy loss processes during propagation or the limits of source acceleration. The shape of this suppression and its interpretation continue to be refined as exposure grows and analysis techniques evolve.

Large-Scale Anisotropies and Hotspots

Arrival direction studies at ultra-high energies have identified large-scale anisotropies—such as dipole-like patterns—that may reflect the distribution of nearby extragalactic matter and intergalactic magnetic fields. Reports of regional excesses (hotspots) in certain sky areas have prompted extensive follow-up, with collaborations comparing results across hemispheres. As statistics accumulate, patterns in arrival directions provide critical clues about source populations and magnetic deflections.

Interpreting anisotropy requires careful accounting of detector exposure, energy calibration, and composition. Nonetheless, the presence of large-scale features supports the view that the highest-energy cosmic rays originate beyond the Milky Way and that their paths are not completely randomized by magnetic fields.

Multi-Messenger Connections

Cosmic-ray science sits at the nexus of multi-messenger astrophysics. High-energy neutrinos, gamma rays, and gravitational waves all enrich the context in which cosmic-ray sources are studied. For example, gamma-ray observations of SNRs and AGN illuminate acceleration sites and target densities, while high-energy neutrinos point to hadronic interactions in extreme environments. Correlating cosmic-ray anisotropy with these messengers is an active frontier promising deeper insight into the most energetic processes in the Universe.

Frequently Asked Questions

Are cosmic rays dangerous to humans at ground level?

At sea level, the atmosphere provides substantial shielding. The average person’s exposure from cosmic rays at ground level is relatively low compared to other sources of natural background radiation. People who fly frequently, airline crew, and astronauts encounter higher exposures because of reduced shielding at altitude and in space. Aviation radiation is monitored, and space missions incorporate safety measures as discussed in Radiation Impacts: Aviation, Spaceflight, and Electronics.

Can cosmic rays be used to image structures like volcanoes or pyramids?

Yes. Muon tomography exploits the penetration power of atmospheric muons—secondary particles from cosmic-ray showers—to image the interior density of large objects. By measuring the attenuation of muons passing through a structure, scientists can infer density variations. This technique has been applied to volcano monitoring, industrial inspections, and archaeological studies of large stone structures. It is a striking example of how air-shower secondaries enable practical applications beyond astrophysics.

Final Thoughts on Understanding Cosmic Rays

Cosmic rays trace a story that begins in the most energetic corners of the Universe—shocks from supernovae, pulsar magnetospheres, and the colossal jets of active galaxies—and continues through a labyrinth of magnetic fields and interstellar matter before finishing in our atmosphere. Along the way, this high-energy radiation sculpts a spectrum marked by the knee and ankle, reshaped by propagation and heliospheric modulation, culminating in the showers that spatter Earth’s surface with particles we can measure.

From a practical standpoint, cosmic rays matter. They define a background radiation environment for aviation and spaceflight, drive reliability strategies in electronics, and even enable innovative imaging via muon tomography. At the same time, they remain a key to unlocking high-energy astrophysics: experiments now routinely produce precision spectra, composition, and anisotropy measurements that constrain source models at GeV through EeV energies.

Looking ahead, improvements in detector sensitivity, multi-messenger coordination, and theoretical modeling promise sharper answers to classic questions: Which accelerators dominate at different energies? How does composition evolve from the Galactic to the extragalactic regime? What role do magnetic fields play in shaping the highest-energy sky? If you found this guide useful, explore more of our deep-dive astrophysics articles and subscribe to our newsletter to get new science features delivered to your inbox.