Table of Contents

- What Is Europa, Jupiter’s Ocean World?

- Discovery, Orbit, and Physical Properties of Europa

- Ice Shell, Surface Geology, and Tectonics on Europa

- Evidence for a Global Subsurface Ocean

- Chemistry, Energy Sources, and Habitability Potential

- Plumes, Thin Atmosphere, and Jupiter’s Harsh Radiation

- How to Observe Europa from Earth: Transits, Eclipses, and Events

- From Voyager to Europa Clipper: Missions and What They’ll Teach Us

- Key Science Questions and What Comes Next After Clipper and JUICE

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Final Thoughts on Choosing the Right Europa Observation Strategy

What Is Europa, Jupiter’s Ocean World?

Europa is one of the four large Galilean moons of Jupiter and a leading candidate in the search for life beyond Earth. Beneath its glistening ice shell, multiple lines of evidence point to a global, salty ocean in contact with a rocky seafloor. This pairing—liquid water, rock, and energy—makes Europa a cornerstone target for planetary science and astrobiology.

When you look at Jupiter through a small telescope, Europa appears as a faint pinpoint of light, often just a little closer to the planet than its siblings Io, Ganymede, and Callisto. But that unassuming dot hides a complex world: a dynamic ice shell patterned with long, intersecting ridges; vast patches of broken, rafted blocks known as chaos terrain; and chemical signatures that suggest salts and oxidants reach the surface from within. Together, these features fuel the modern vision of Europa as an ocean world—and a natural laboratory for understanding habitability.

This article explores Europa’s orbit and physical traits, the geological processes sculpting its surface, the evidence for and structure of the subsurface ocean, the astrobiological potential of this Jovian moon, and the missions poised to transform our understanding in the coming decade. You will also find practical guidance on observing Europa from your backyard and how to follow the science data to come. For readers wanting to jump ahead, you can explore the observational tips in How to Observe Europa, or dive into mission specifics in From Voyager to Europa Clipper. To understand why Europa is considered habitable, read Chemistry, Energy Sources, and Habitability.

Discovery, Orbit, and Physical Properties of Europa

Europa was discovered in January 1610 by Galileo Galilei, alongside Io, Ganymede, and Callisto. These moons fundamentally changed our understanding of the cosmos by providing clear evidence that not everything revolves around Earth. Europa’s small size and brightness hint at its composition and surface youthfulness, but the details emerged only with modern spacecraft exploration.

Basic dimensions and composition

- Diameter: about 3,121 kilometers, a bit smaller than Earth’s Moon.

- Bulk density: consistent with a mixture of rock and water ice, with a water-rich outer shell atop a rocky interior.

- Surface: dominated by water ice, with coloration and spectral signatures suggesting salts and radiation-processed compounds mixed in.

Europa’s icy exterior reflects sunlight efficiently. The bright albedo and paucity of impact craters indicate a geologically young surface refreshed by internal processes. The ocean is inferred to reside beneath this shell, possibly dozens of kilometers below, and may be roughly 100 kilometers deep—deep enough that its total water volume likely exceeds Earth’s oceans combined.

Orbit and rotation in Jupiter’s system

- Orbital period: about 3.55 Earth days.

- Synchronous rotation: Europa keeps the same face toward Jupiter, much like our Moon does with Earth.

- Eccentricity: small but non-zero, maintained by gravitational interactions within the Laplace resonance with Io and Ganymede.

Europa’s slightly elongated orbit causes regular flexing of its interior through tidal forces. This flexing dissipates energy as heat, which keeps parts of the interior warm and is central to sustaining the subsurface ocean. The same mechanism powers active volcanism on Io and likely drives internal dynamics on Europa, just in a different form. For a deeper dive on how tides create internal heat, see Chemistry, Energy Sources, and Habitability Potential.

Radiation environment

Europa orbits deep within Jupiter’s intense magnetosphere. Energetic particles bombard the surface, creating a constantly refreshed, tenuous atmosphere (exosphere) and altering surface chemistry through radiolysis. The radiation dose on the surface can reach levels that would be lethal to unprotected organisms in short order. This harsh environment shapes not only Europa’s surface composition but also the strategies spacecraft must use to survive and collect data, as described in From Voyager to Europa Clipper.

Ice Shell, Surface Geology, and Tectonics on Europa

Europa’s surface is a tapestry of geologic forms carved into the ice shell. These features are clues to the processes operating above a global ocean and hint that the ice shell itself is mobile, fractured, and possibly convective.

Ridges, bands, and lineae

The most striking features are the many long, dark streaks and double ridges that crisscross the surface. These ridge systems can extend hundreds or even thousands of kilometers, sometimes with parallel flanks separated by a central groove. Their formation likely involves repeated opening and closing of cracks, intrusion of warm ice or brine, and the accumulation of materials that darken with exposure to radiation.

- Double ridges may form as pressurized water or brine is forced into a crack and then freezes, uplifting the surface around it.

- Dilational bands appear as regions where the crust has pulled apart, potentially exposing fresher ice from below and producing linear zones of lighter material.

- Lineae (lines) trace fracture patterns, marking stress fields within the shell that can change over time as tides flex the moon.

Chaos terrain and resurfacing

Chaos terrain consists of jumbled blocks of icy crust that appear to have drifted, rotated, and re-frozen in place. These regions can span hundreds of kilometers and suggest localized heating that disrupts the ice shell. Hypotheses for their formation include melt or partial melt within the shell, diapirism (warm ice rising), or intrusion of brines that reduce the ice’s strength. While the exact mechanisms remain debated, chaos terrain demonstrates that Europa’s shell is not static. The scale of resurfacing, along with the low number of impact craters, indicates that portions of the surface are geologically young on million-year timescales.

Possible plate-like behavior

Some lines of evidence suggest that Europa may exhibit plate-like tectonics. In places, geologists have identified areas that appear to be missing material, which could imply that surface plates have been driven downward and recycled. While full-scale plate tectonics analogous to Earth’s remains unproven, the observations are consistent with some form of lateral motion and subduction-like processes in the ice shell. This matters for habitability: if oxidants and nutrients from the surface can be transported downward, they may feed the ocean below. You can connect this idea to oxidant delivery in Chemistry, Energy Sources, and Habitability Potential.

Thermal structure and thickness of the ice shell

Determining the thickness of Europa’s ice shell is a major goal of upcoming missions. Estimates often fall in the range of several to a few tens of kilometers. If the ice is thick but warm enough in its lower layers to deform, convection may transport materials and heat, connecting the ocean to the surface over geological time. If it’s thinner in some areas, brines or plumes might occasionally reach near-surface levels, a scenario explored further in Plumes, Thin Atmosphere, and Jupiter’s Harsh Radiation.

Evidence for a Global Subsurface Ocean

The case for an ocean beneath Europa’s ice shell rests on multiple, independent observations. Together, these lines of evidence form a coherent picture of an ocean world.

Induced magnetic fields

One of the most compelling clues comes from measurements of the magnetic field around Europa. As Jupiter’s magnetic environment sweeps past the moon, it induces electrical currents in conductive layers. The data are best explained by a salty, global ocean beneath the ice. The salinity implies the presence of dissolved ions—potentially sourced from the rocky interior or the breakdown of surface materials—and a thickness sufficient to sustain induction.

Surface geology consistent with an active shell

The network of ridges, bands, and chaos terrain indicates ongoing interior activity. Tidal flexing can open and close fractures, circulate fluids, and heat the shell. Combined with a young surface age inferred from crater counts, these observations point toward an internal heat source that maintains liquid water beneath the crust.

Thermal and density models

Models of Europa’s interior that match the observed mass and moment of inertia require a relatively low-density outer layer consistent with an ice-water shell. Thermal models that include tidal heating predict that portions of this shell can be warm enough to sustain a global ocean over geological time. These models dovetail with magnetic induction results and geological inferences, reinforcing the ocean hypothesis.

Plume candidates and fresh exposures

Some observations from Earth and space-based telescopes have been interpreted as possible water vapor plumes erupting from Europa. While not yet confirmed beyond doubt, the evidence suggests that occasional outgassing may occur. If plumes are present, they could provide an opportunity to sample ocean-derived materials without drilling through the ice—an approach future missions may exploit. Note that plume interpretations must be handled cautiously; see the discussion in Plumes, Thin Atmosphere, and Jupiter’s Harsh Radiation for context and caveats.

Convergence matters: magnetometer induction, geological evidence of resurfacing, and interior models all point toward the same conclusion—Europa is very likely an ocean world.

Chemistry, Energy Sources, and Habitability Potential

Habitability is not just about the presence of liquid water. Life as we know it also needs sources of energy and essential chemical building blocks. Europa plausibly provides these ingredients, though the question of life remains open.

Water and salts

Europa’s global ocean likely contains dissolved salts, making it electrically conductive. Spectral evidence from the surface points to salts that could include sulfates and chlorides. Some regions display coloration different from pure water ice, consistent with irradiated brines or salt hydrates that have been exposed at or near the surface. If surface salts originate in the ocean and are cycled upward, analyzing them can reveal the ocean’s composition.

Energy sources: tidal heating and hydrothermal systems

Tidal flexing is the primary source of heat in Europa’s interior. The varying gravitational pull from Jupiter and the orbital resonance with Io and Ganymede keep Europa’s orbit slightly elliptical, and this constant flexing dissipates energy as heat—especially in the ice shell and the underlying rocky mantle. Where the ocean meets the rock, hydrothermal circulation may occur. On Earth, hydrothermal vents support rich ecosystems independent of sunlight. If similar systems exist on Europa’s seafloor, they could provide chemical energy and gradients life could exploit.

- Serpentinization: Reactions between water and certain rock types can produce hydrogen, a key energy source for microbial life on Earth.

- Redox gradients: Oxidants produced on the surface via radiation may be transported to the ocean, potentially fueling metabolisms if they meet reduced compounds at depth.

Surface oxidants and downward transport

Radiation in Jupiter’s magnetosphere splits water molecules on Europa’s surface, generating oxidants like molecular oxygen and hydrogen peroxide. If the ice shell transports even a fraction of these oxidants downward—through cracks, melting, subduction-like processes, or convection—they could mix with reduced chemicals from the interior. This coupling, discussed earlier in Ice Shell, Surface Geology, and Tectonics on Europa, is one way to create an ocean environment that might sustain metabolism.

The habitability checklist

Planetary scientists often frame habitability around the co-presence of liquid water, energy sources, and essential elements (CHNOPS—carbon, hydrogen, nitrogen, oxygen, phosphorus, sulfur). Europa likely meets the first criterion and has plausible paths for the second and third:

- Water: Global subsurface ocean indicated by magnetic induction and thermal models.

- Energy: Tidal heating, possible hydrothermal vents, and surface-derived oxidants.

- Chemistry: Salts, potential organics delivered by comets/micrometeorites, and rock-water interactions.

Whether these ingredients actually come together in ways that produce or sustain life remains unknown. That is precisely what upcoming missions are designed to assess—indirectly—by characterizing ocean composition, ice shell processes, and energy availability. The instruments and strategies to address these questions are detailed in From Voyager to Europa Clipper.

Plumes, Thin Atmosphere, and Jupiter’s Harsh Radiation

Europa’s near-vacuum atmosphere and potential plume activity add complexity to its story, with important implications for both habitability and mission design.

A tenuous oxygen atmosphere

Europa possesses a very thin atmosphere, better described as an exosphere, dominated by molecular oxygen (O2). This oxygen is not biological; it is produced by radiolysis—high-energy particles striking the surface and breaking water molecules into hydrogen and oxygen. Hydrogen, being light, escapes more readily, leaving oxygen behind. The exosphere is continually replenished as radiation processes the surface ice. Though extremely tenuous compared with Earth’s atmosphere, this O2 reservoir is a useful tracer of surface chemistry and radiation effects.

Plume candidates and what they mean

There have been reports of transient water vapor detections above Europa, interpreted by some as evidence of plumes that could reach up to hundreds of kilometers in height. The observations, while intriguing, are challenging and remain an active area of study. If plumes are present:

- They could provide direct access to ocean-derived materials via fly-through sampling.

- They may indicate active conduits through the ice shell, offering windows into interior processes.

- They could vary with tidal stress, hinting at a linkage to Europa’s orbital flexing.

Because plume detections are not yet definitive, future missions will carry instruments capable of searching for them systematically. For how mission plans account for this possibility, see From Voyager to Europa Clipper.

Radiation hazards and surface chemistry

Jupiter’s magnetosphere creates a harsh radiation environment at Europa’s orbit. The surface is bathed in energetic electrons and ions that alter exposed materials over relatively short timescales. This radiation:

- Drives chemical reactions that produce oxidants (O2, H2O2), changing the chemistry of surface ice.

- Darkens and reddens the surface where salts and other substances are mixed with ice, contributing to the moon’s distinctive coloration.

- Poses significant risks to spacecraft and requires careful planning for electronics shielding, flight paths, and instrument duty cycles.

The radiation also matters for biosignature preservation. If materials from the ocean are transported to the surface, they will be altered by radiation quickly—so sampling fresh exposures or shielded materials, such as those within cracks or recently formed features, may be crucial for astrobiological investigations. This is a key reason that low-altitude flybys targeting specific terrains are part of mission strategies described in From Voyager to Europa Clipper.

How to Observe Europa from Earth: Transits, Eclipses, and Events

Although Europa’s ocean remains hidden, you can observe the moon itself with modest backyard equipment. Watching Europa and its siblings dance around Jupiter is one of the great rewards of amateur astronomy.

What you can see with binoculars and small telescopes

- Binoculars (10×50): Under steady hands or with a mount, you can often spot one or more Galilean moons as tiny points near Jupiter; identifying which one is which requires a chart or app.

- Small telescopes (60–100 mm): All four Galilean moons are routinely visible as star-like points. You can track their changing positions over the course of a few hours.

- Medium telescopes (150–200 mm): Look for events like transits (a moon crossing Jupiter’s face), occultations (a moon passing behind Jupiter), and eclipses (a moon entering Jupiter’s shadow). Under excellent seeing, you may glimpse Europa’s shadow on Jupiter as a small, inky dot during a transit.

Timing mutual events

Europa completes an orbit around Jupiter roughly every 3.55 days, so interesting geometries recur frequently. To plan observations:

- Use reputable ephemeris tools to obtain Europa’s position, transit times, and shadow paths for your location.

- Note that Europa is sometimes very close to Jupiter’s glare; higher magnification and good seeing help.

- Keep a log of what you see—over multiple nights you will develop intuition for Europa’s motion relative to Io, Ganymede, and Callisto.

2025-01-xx 22:30 local | Scope: 100 mm refractor | Seeing: 7/10 | Target: Jupiter & Europa

Europa east of Jupiter, ~2 arcmin | Notes: Slight elongation at high mag (seeing limit) | Next: Check transit schedule for tomorrow.

Astrophotography ideas

Imaging Jupiter and Europa can be rewarding. Planetary imagers often record short video sequences at high frame rates and stack the best frames to overcome turbulence. Tips include:

- Use a planetary camera or DSLR in video mode; keep exposures short.

- Capture multiple sequences across 15–30 minutes to allow derotation in software if needed.

- For Europa transit shadows, aim for steady seeing and a high-contrast processing workflow.

While you cannot resolve Europa’s surface features from Earth with amateur gear, tracking its motions and events builds an intuitive understanding of the Jovian system’s dynamics. For more about the system’s resonance and tidal interactions, refer back to Discovery, Orbit, and Physical Properties of Europa.

From Voyager to Europa Clipper: Missions and What They’ll Teach Us

Our knowledge of Europa has come primarily from spacecraft and telescopic observations. Each mission has added a layer of understanding, culminating in upcoming dedicated campaigns designed to answer the most pressing questions about ocean structure, chemistry, and habitability.

Voyager and the first close looks

In 1979, the Voyager 1 and 2 spacecraft provided humanity’s first detailed views of Europa’s surface. The images revealed a bright, relatively smooth world crisscrossed by dark lines and with far fewer impact craters than expected. These early observations raised the possibility that Europa’s surface was young and active.

Galileo’s transformative science

NASA’s Galileo spacecraft, which orbited Jupiter from 1995 to 2003, delivered the most influential Europa dataset to date. Key contributions include:

- Magnetometer results: Indications of a conductive, global subsurface ocean through magnetic induction signatures.

- Imaging: High-resolution views of ridges, chaos terrain, and other features consistent with active resurfacing.

- Infrared and spectral data: Evidence for water ice mixed with other materials, including salts possibly derived from the ocean or from rock-water interactions.

Galileo’s observations made a powerful, multi-pronged case for an ocean under Europa’s ice shell and set the stage for future missions focused on habitability.

Jupiter flybys and telescopes

Other spacecraft and telescopes have added context:

- New Horizons obtained additional views during its 2007 Jupiter flyby, complementing earlier datasets.

- Hubble Space Telescope made sensitive observations of Europa’s tenuous environment, including reports of possible transient water vapor above the surface.

- Ground-based observatories have contributed detections of surface chemistry and thermal characteristics, within the constraints of Earth’s atmosphere and distance.

ESA’s JUICE mission

The European Space Agency’s Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer (JUICE), launched in 2023, is en route to the Jovian system. Its primary focus is Ganymede, with additional flybys of Callisto and Europa. Although JUICE plans fewer Europa encounters than a dedicated mission, those flybys will provide valuable measurements of Europa’s surface, environment, and interior signatures. Data synergy between JUICE and NASA’s mission will be significant, as described below.

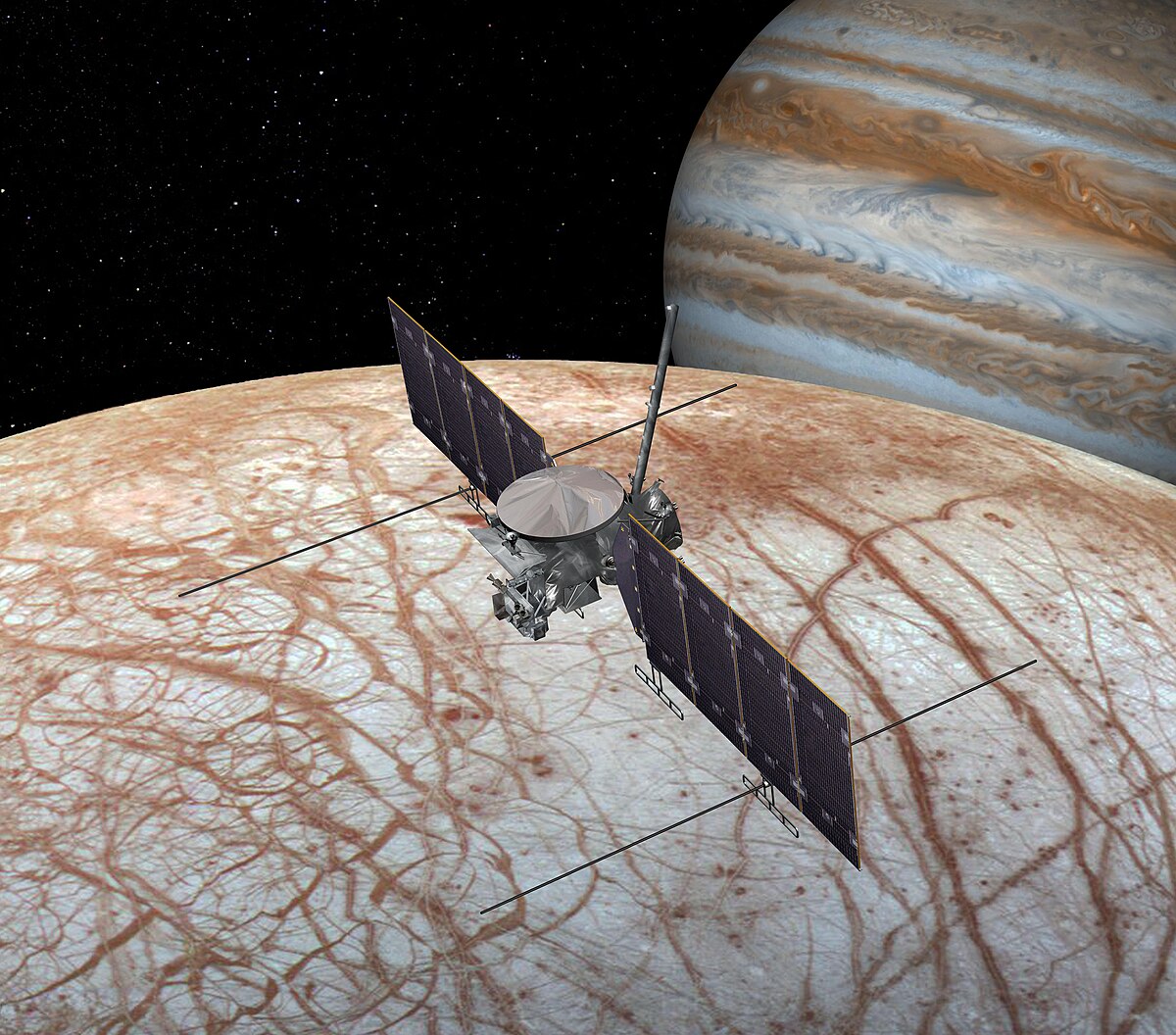

NASA’s Europa Clipper

NASA’s Europa Clipper mission launched in 2024 and is slated to arrive at Jupiter later this decade. Rather than orbiting Europa itself—a challenging feat due to radiation—it will orbit Jupiter and conduct a large number of targeted flybys of Europa at varying altitudes, some very low, to sample different terrains and environments.

Europa Clipper’s scientific payload is optimized to address habitability:

- Ice-penetrating radar to probe the ice shell and search for internal structures, such as brine pockets or layered ice.

- Magnetometry and plasma instruments to refine constraints on the ocean’s depth, salinity, and interaction with Jupiter’s magnetosphere.

- Imaging systems for global context and high-resolution views of geologic features, including ridges and chaos regions.

- Spectrometers (infrared, ultraviolet, and mass spectrometry) to analyze surface composition, search for organics and salts, and sample the exosphere or any plume material encountered.

- Thermal mapping to detect warm spots that could indicate recent activity, fractures, or shallow reservoirs.

While Europa Clipper is not a life-detection mission, it is designed to assess Europa’s habitability. It will examine the ice shell’s structure, the nature of the ocean, and the availability of chemical energy—laying the groundwork for any future mission that might attempt to sample ocean-derived materials more directly. If potential plumes are identified or confirmed, Clipper can adapt flyby strategies to increase the likelihood of sampling them. This agile approach is a response to the uncertainties highlighted in Plumes, Thin Atmosphere, and Jupiter’s Harsh Radiation.

Radiation mitigation and operations

The mission designs to Europa factor in Jupiter’s radiation environment. Electronics require careful shielding, flybys are choreographed for scientific return while minimizing cumulative radiation, and instruments are operated in ways that balance sensitivity with longevity. These strategies reflect lessons learned from past missions and the specific challenges of Europa’s orbit.

Key Science Questions and What Comes Next After Clipper and JUICE

The upcoming decade promises a renaissance in Europa science. Europa Clipper and JUICE will together address a suite of big questions whose answers will guide the next generation of exploration.

How thick is the ice, and how does it move?

Determining ice shell thickness—and whether it varies regionally—will help us understand how materials cycle between the surface and the ocean. Ice-penetrating radar and gravity measurements can reveal layering, brine pockets, and other structures. If signs of subduction-like behavior are found, they would bolster the case for downward transport of surface oxidants discussed in Chemistry, Energy Sources, and Habitability Potential.

What is the ocean’s composition?

Constraining the ocean’s salinity, pH, and dissolved constituents is essential for habitability assessments. Surface spectroscopy and exosphere sampling can provide indirect indicators of ocean chemistry. The presence of certain salts or organic molecules would guide models of rock–water interactions and potential energy pathways for life.

Are there active plumes, and how often do they occur?

Repeated, targeted observations can test whether plume activity is present and whether it correlates with tidal cycles. If plumes are detected, in situ sampling during flybys—using mass spectrometers and dust analyzers—could measure isotopic ratios, search for complex organics, and assess whether the material is ocean-derived.

Is there seafloor hydrothermal activity?

Direct detection of hydrothermal vents is beyond the reach of current missions. However, signatures in the ocean’s composition, magnetic data, and thermal models could point to rock–water interactions at the seafloor. If these processes are active, they strengthen the case for Europa’s habitability by supplying chemical energy, as outlined in Chemistry, Energy Sources, and Habitability Potential.

What would a future lander or sample-return mission require?

Should Europa Clipper identify regions with fresh materials, high astrobiological potential, or recurring activity, those areas could become targets for a future lander. Such a mission would face challenges: surviving radiation, ensuring planetary protection, and sampling materials that are representative of the ocean. The answers from Clipper and JUICE will refine the designs and objectives of any subsequent mission.

Synergy with other ocean worlds

Comparisons with other ocean worlds, notably Saturn’s moon Enceladus, will be important. While Enceladus has confirmed plumes sourced from a global ocean, Europa is larger, experiences stronger tides, and orbits in a harsher radiation environment. Together, studies of these moons will help us understand the diversity of habitable environments in our solar system and the types of biosignatures different ocean worlds might produce.

Frequently Asked Questions

Is Europa more likely to host life than other icy moons?

Comparing “likelihood” is difficult because each ocean world offers different advantages. Enceladus provides direct plume access to ocean material, while Europa likely has a deeper ocean with strong tidal energy and a rocky seafloor that may host hydrothermal activity. Europa’s strong radiation environment could produce abundant oxidants at the surface that may, if transported downward, drive ocean chemistry. Ultimately, the case for life hinges on the interplay of water, energy, and chemical gradients, which the next missions aim to quantify.

When will Europa Clipper arrive and what will it measure first?

Europa Clipper launched in 2024 and is expected to arrive at Jupiter later this decade, after a series of gravity assists. Following orbital insertion around Jupiter, the spacecraft will begin a campaign of close flybys of Europa, progressively building a global dataset. Early measurements typically focus on instrument checkouts and global context imaging, followed by increasingly targeted observations—such as low-altitude passes over key geologic terrains and exosphere sampling that can test for plume activity. The mission timeline prioritizes both broad mapping and high-value, focused science.

Final Thoughts on Choosing the Right Europa Observation Strategy

Europa stands at the nexus of geology and astrobiology. For backyard observers, the “right” observation strategy begins with patience and planning: track Europa’s transits, eclipses, and occultations to appreciate its orbital rhythm; log observations to hone your skills; and when imaging, choose steady nights and short exposures to capture delicate shadow events. For those following the science, tailor your “observation strategy” to your interests—ocean structure, plume searches, or surface chemistry—and focus on the instrument datasets and analyses that address those themes. Link your reading across topics: for example, tie geologic resurfacing in Ice Shell, Surface Geology, and Tectonics on Europa to ocean evidence in Evidence for a Global Subsurface Ocean, and then to energy pathways in Chemistry, Energy Sources, and Habitability Potential.

In the coming years, JUICE and Europa Clipper will transform Europa from a tantalizing “ocean beneath ice” hypothesis into a richly quantified world. Expect refined estimates of ice thickness, ocean salinity, and heat flow; global maps of geologic terrains; and targeted searches for active phenomena. None of this guarantees life—but it will give us the clearest picture yet of whether Europa’s ocean could be habitable and where to look next.

Key takeaways:

- Independent evidence points to a global subsurface ocean beneath Europa’s ice shell.

- Tidal heating, possible hydrothermal activity, and surface oxidants could together create habitable conditions.

- Radiation sculpts the surface chemistry and challenges spacecraft design, shaping mission strategies.

- Europa Clipper and JUICE will deliver the data needed to test plume activity, characterize the ice and ocean, and identify high-priority sites for future exploration.

If Europa inspires you, consider exploring more articles on ocean worlds and astrobiology, and subscribe to our newsletter to get updates as new mission results arrive. The next decade promises answers to questions that have captivated scientists and skywatchers for generations.