Table of Contents

- What Is Stellar Nucleosynthesis? A Clear Definition and Why It Matters

- Hydrogen Burning: The Proton–Proton Chain and the CNO Cycle

- Helium Burning: The Triple-Alpha Process and Beyond

- Advanced Burning Stages in Massive Stars: Carbon, Neon, Oxygen, and Silicon

- Explosive Nucleosynthesis in Supernovae: Iron Peak Elements and More

- Where the Heaviest Elements Come From: The r-Process and Neutron Star Mergers

- Slow Neutron Capture in AGB Stars: The s-Process and Cosmic Recycling

- How We Know: Observational Signatures from Neutrinos to Spectral Lines

- Chemical Evolution of Galaxies: From Population III to the Present Milky Way

- Big Bang Nucleosynthesis vs. Stellar Nucleosynthesis: Who Made What?

- Nuclear Reaction Rates, the Gamow Peak, and Neutrino Physics

- What We Don’t Yet Know: Modeling Challenges and Nuclear Physics Uncertainties

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Final Thoughts on Understanding Stellar Nucleosynthesis

What Is Stellar Nucleosynthesis? A Clear Definition and Why It Matters

Stellar nucleosynthesis is the set of nuclear fusion and neutron-capture processes by which stars build chemical elements from lighter nuclei. Beginning with hydrogen and helium—the two most abundant elements left over from the early universe—stars act as cosmic furnaces, forging new elements in their cores and envelopes over millions to billions of years. These processes are central to understanding the origin of the periodic table, the life cycles of stars, and the chemical evolution of galaxies.

At its heart, nucleosynthesis is a balance between gravity, which compresses stellar matter, and the pressure and energy released by nuclear reactions. As stars evolve, their core temperatures and densities change, turning on new reaction channels that transform the star’s composition. Small stars primarily convert hydrogen into helium; massive stars progress through a sequence of burning stages, ultimately yielding iron-group elements before ending their lives violently and ejecting the newly made elements into space.

Why does this matter beyond astrophysics? The answer is in your surroundings. The carbon in your body and the oxygen you breathe were fused inside earlier generations of stars. The calcium in your bones and the iron in your blood were made by advanced burning stages or in supernova explosions. The gold in jewelry likely originated in high-neutron-density events such as neutron star mergers. Understanding stellar nucleosynthesis connects fundamental nuclear physics to the evolution of the cosmos and even to planetary and biological evolution.

To see the full picture, we will trace the main fusion cycles that power stars—from the proton–proton chain and CNO cycle to helium burning and advanced burning stages—and then explore explosive pathways in supernovae and the rapid neutron-capture (r-) process. Along the way, we will examine observational evidence in neutrino detections and spectroscopy, and we will place these processes into the broader context of galactic chemical evolution and primordial nucleosynthesis.

Hydrogen Burning: The Proton–Proton Chain and the CNO Cycle

Hydrogen burning is the first and longest phase of stellar life for most stars. It refers to a set of fusion reactions that convert hydrogen (protons) into helium, releasing energy that counteracts gravitational collapse. Two dominant channels operate depending on the star’s mass and core temperature: the proton–proton (pp) chain and the carbon–nitrogen–oxygen (CNO) cycle.

Proton–Proton Chain: The Primary Power Source of Sun-like Stars

In stars up to roughly the Sun’s mass, the pp chain dominates. The chain proceeds through several branches; the most common includes:

p + p → d + e⁺ + νₑ

d + p → ³He + γ

³He + ³He → ⁴He + 2p (pp I branch)

Other branches (pp II and pp III) involve interactions with beryllium and boron isotopes:

³He + ⁴He → ⁷Be + γ

⁷Be + e⁻ → ⁷Li + νₑ

⁷Li + p → 2 × ⁴He (pp II)

⁷Be + p → ⁸B + γ

⁸B → ⁸Be* + e⁺ + νₑ; ⁸Be* → 2 × ⁴He (pp III)

The pp chain is sensitive to temperature but significantly less so than the CNO cycle. This means Sun-like stars can steadily fuse hydrogen over billions of years. Direct evidence for the pp chain comes from solar neutrino measurements that have detected neutrinos from multiple steps in the chain, including the rare but energetic 8B neutrinos.

The CNO Cycle: Hydrogen Burning Catalyzed by Heavier Elements

In stars more massive than the Sun, the CNO cycle becomes the dominant hydrogen-burning pathway because its reaction rates increase steeply with temperature. It uses carbon, nitrogen, and oxygen as catalysts to convert four protons into one helium nucleus:

¹²C(p,γ)¹³N(β⁺)¹³C(p,γ)¹⁴N(p,γ)¹⁵O(β⁺)¹⁵N(p,α)¹²C

Although the catalysts are restored, the cycle establishes a quasi-equilibrium abundance pattern where 14N tends to accumulate. At sufficiently high temperatures, additional branches (like the CNO bi-cycle) can operate, producing isotopes such as 17O and 18O. In recent years, detectors have directly observed CNO neutrinos, offering a complementary window into this process and confirming that massive and metal-rich stars can be powered largely by the CNO cycle.

Understanding whether the pp chain or the CNO cycle dominates in a given star sets the initial conditions for subsequent evolution: the core temperature, density, and composition resulting from hydrogen burning control when and how the star transitions to helium burning.

Helium Burning: The Triple-Alpha Process and Beyond

Once a star has built up a helium-rich core, the next evolutionary milestone is helium burning. In Sun-like stars, helium ignites after the main sequence when the core contracts and heats; in low-mass red giants with degenerate cores, the onset can be explosive—a helium flash—though the star’s envelope buffers observers from a dramatic external display. In more massive stars, helium burning begins more gently.

The Triple-Alpha Process

The triple-alpha reaction builds carbon from helium in a two-step sequence:

⁴He + ⁴He ⇌ ⁸Be

⁸Be + ⁴He → ¹²C* → ¹²C + γ

The nucleus 8Be is unstable, but at high temperature and density, a small equilibrium abundance exists long enough for a third alpha particle to fuse, creating an excited state of 12C that decays to ground state, releasing a gamma ray. This process is exquisitely sensitive to temperature—an increase in core temperature can dramatically raise the energy generation rate, affecting stellar structure and luminosity.

Alpha-Capture on Carbon: Building Oxygen and Neon

As helium burning proceeds, alpha capture can extend the chain:

¹²C(α,γ)¹⁶O

¹⁶O(α,γ)²⁰Ne

The competition between these reactions largely controls the final 12C/16O ratio in the core, which affects subsequent burning stages, white dwarf composition, and the yields of core-collapse supernovae. The rate of ¹²C(α,γ)¹⁶O at stellar energies is therefore a key uncertainty in models (see Modeling Challenges).

After helium is exhausted in the core, helium burning can continue in shells around an inert core of carbon and oxygen, while hydrogen burning persists in an outer shell. The interaction of these shells and the mixing they induce can dredge up freshly synthesized elements to the stellar surface, especially in asymptotic giant branch (AGB) stars.

Advanced Burning Stages in Massive Stars: Carbon, Neon, Oxygen, and Silicon

Massive stars (roughly greater than eight times the Sun’s mass) proceed through a ladder of increasingly rapid and hot burning stages as their cores contract and heat after each fuel is exhausted. Each stage fuses heavier nuclei, brings the core closer to nuclear statistical equilibrium, and operates on shorter timescales.

Carbon Burning

At core temperatures of about 0.6–1 billion K, carbon fuses via channels such as:

¹²C + ¹²C → ²⁰Ne + α

¹²C + ¹²C → ²³Na + p

¹²C + ¹²C → ²⁴Mg + γ

The branching among these channels depends on temperature and density. Carbon burning generates neon, sodium, magnesium, and various light particles (alpha particles, protons). Neutrino losses become significant, cooling the core and hastening the star’s evolution.

Neon Burning

Neon burning is triggered largely by photodisintegration. At higher temperatures, gamma rays disassemble 20Ne:

²⁰Ne(γ,α)¹⁶O

The liberated alpha particles then capture on neon or oxygen to form heavier elements. This stage proceeds quickly compared to earlier phases because of efficient neutrino cooling, which forces the core to contract and heat further.

Oxygen Burning

Oxygen burning at temperatures near 1.5–2.5 billion K fuses oxygen nuclei through channels like:

¹⁶O + ¹⁶O → ²⁸Si + α

¹⁶O + ¹⁶O → ³¹P + p

¹⁶O + ¹⁶O → ³²S + γ

This phase builds up silicon, sulfur, phosphorus, and chlorine, among others. As with earlier stages, the mixture of products sets the seed composition for the next burning phase and for potential explosive processing if the star undergoes a supernova.

Silicon Burning and Nuclear Statistical Equilibrium

Silicon burning is the final fusion stage before core collapse in massive stars. It occurs at temperatures exceeding roughly 3 billion K and proceeds not by simple fusion, but through a complex network of photodisintegration and capture reactions. The intense radiation field tears apart heavy nuclei into alpha particles, protons, and neutrons, which then recapture onto other nuclei. Over time, the system approaches quasi-equilibrium and eventually nuclear statistical equilibrium (NSE), where abundances are governed mainly by nuclear binding energies and the thermodynamic state.

In NSE under typical core-collapse conditions, the composition favors iron-peak elements—particularly 56Ni, which later decays to 56Co and then to stable 56Fe. The amount of 56Ni synthesized has a strong influence on the brightness of the ensuing supernova light curve, especially in Type II and Type Ib/c explosions (see Explosive Nucleosynthesis).

Explosive Nucleosynthesis in Supernovae: Iron Peak Elements and More

When massive stars exhaust nuclear fuel, their cores—dominated by iron-group nuclei—can no longer support themselves against gravity through fusion. Electron captures reduce pressure, and the core collapses, leading to a core-collapse supernova (Type II, Ib, or Ic). Conversely, Type Ia supernovae arise from thermonuclear runaway in carbon–oxygen white dwarfs, typically in binary systems, igniting near the Chandrasekhar mass or through sub-Chandrasekhar scenarios.

Core-Collapse Supernovae (CCSNe)

During core collapse, the inner core rebounds when nuclear densities are reached, launching a shock wave. The shock initially stalls but can be revived by neutrino heating and multidimensional instabilities, driving an explosion that ejects outer layers. In the intense heat of the shock front, explosive nucleosynthesis occurs:

- Explosive oxygen and silicon burning create iron-peak nuclei, including 56Ni.

- Alpha-rich freeze-out in expanding, hot material can produce elements like 44Ti.

- Neutrino interactions with nuclei can alter electron fractions (Ye), affecting yields of elements from iron to zinc.

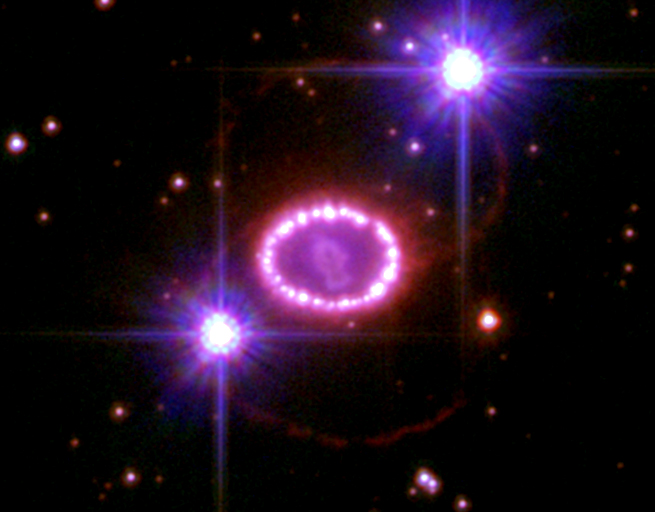

The relative distribution of these products depends on the progenitor mass, metallicity, rotation, and details of the explosion mechanism. Observations of supernova remnants and gamma-ray lines (e.g., from 44Ti decay in some remnants) provide evidence for these processes.

Type Ia Supernovae

Thermonuclear supernovae predominantly synthesize iron-peak elements via rapid burning of carbon and oxygen under degenerate conditions. The high densities enable electron capture, affecting the distribution of isotopes such as nickel, cobalt, and manganese. Type Ia supernovae are major contributors to 56Fe (produced as 56Ni) in galaxies and are crucial to the evolution of [α/Fe] abundance ratios in stellar populations.

Explosive environments also influence neutron-capture pathways. While some r-process material may be produced in special core-collapse or magneto-rotational explosions, compelling evidence points to neutron star mergers as dominant sites for the heaviest r-process elements.

Where the Heaviest Elements Come From: The r-Process and Neutron Star Mergers

The rapid neutron-capture process (r-process) builds very heavy elements—such as gold, platinum, and uranium—by rapidly adding neutrons to seed nuclei. The neutron flux and densities are so high that multiple captures occur before nuclei can beta-decay back toward stability. When the neutron supply dwindles, the neutron-rich isotopes decay, populating the heavy side of the periodic table.

For decades, the astrophysical sites of the r-process were debated. Evidence now strongly supports merging neutron stars as major sites:

- Multimessenger observations of a binary neutron star merger, including gravitational waves and an optical/infrared kilonova, showed light curves and spectra consistent with the synthesis of heavy, lanthanide-bearing material.

- Abundance patterns in some ancient stars match a universal r-process pattern for elements beyond barium, suggesting a common astrophysical origin.

The ejecta composition depends on how the merger proceeds, including tidal tails, disk winds, and neutrino irradiation, which set electron fractions and thus the final abundance distribution. While neutron star mergers appear to be key r-process factories, research continues on whether certain rare core-collapse supernovae or collapsars also contribute, especially to lighter r-process nuclei. These uncertainties interact with galactic chemical evolution models, which must reconcile the frequency of events with observed abundance trends in the Milky Way.

Slow Neutron Capture in AGB Stars: The s-Process and Cosmic Recycling

The slow neutron-capture process (s-process) synthesizes many elements between iron and lead by adding neutrons at a rate slow compared to beta decays. This path closely follows the valley of stability in the chart of nuclides. The primary astrophysical sites include asymptotic giant branch (AGB) stars, where thermal pulses and convective mixing enable neutron production and transport newly formed elements to the surface.

Neutron Sources in AGB Stars

Two principal reactions provide neutrons:

¹³C(α,n)¹⁶O: Activated at relatively low temperatures during interpulse phases. A localized “¹³C pocket” can form when protons partially mix into 12C-rich layers, creating 13C via¹²C(p,γ)¹³N(β⁺)¹³C.²²Ne(α,n)²⁵Mg: Requires higher temperatures and is activated during thermal pulses, contributing to heavier s-process nuclei and branching points.

These neutron sources, combined with the star’s metallicity and mixing physics, shape the s-process abundance pattern, including the production of elements such as strontium, barium, and lead. Observationally, spectra of some cool giants show technetium lines—evidence of ongoing s-process nucleosynthesis because technetium lacks long-lived stable isotopes.

AGB stars also contribute significantly to the cosmic dust budget. Grains condense in their cool, extended atmospheres and are then carried into space by stellar winds. Meteorites contain presolar grains—tiny solid particles—that retain isotopic fingerprints matching s-process predictions, offering laboratory-scale evidence for AGB nucleosynthesis.

How We Know: Observational Signatures from Neutrinos to Spectral Lines

While nucleosynthesis takes place in distant, opaque stellar interiors, astronomers have developed multiple lines of evidence to test and refine theoretical models.

Solar and Stellar Neutrinos

Neutrinos provide a direct probe of nuclear reactions in stellar cores. Decades of solar neutrino experiments observed fewer electron-flavor neutrinos than standard solar models predicted, a discrepancy resolved by neutrino oscillations, whereby neutrinos change flavor while traveling from the Sun to Earth. The resolution confirmed both the solar fusion processes and the particle physics of neutrinos. Subsequent detectors have measured neutrinos from multiple branches of the pp chain and provided indications of CNO-cycle neutrinos, strengthening constraints on the Sun’s core metallicity and energy production.

Supernova Light Curves and Spectra

Supernova light curves reflect the amount of radioactive 56Ni produced and its decay to 56Co and then 56Fe, which powers the light output over weeks to months. Spectral features reveal velocities, compositions, and ionization states of the ejecta. Combined, these data constrain the nature of the progenitor, the explosion energy, and the yields of iron-peak and intermediate-mass elements. In some remnants, gamma-ray lines from decays like 44Ti provide direct windows on explosive nucleosynthesis zones.

Spectroscopic Abundances in Stars and Gas

High-resolution spectroscopy of stars across the Milky Way’s components (thin disk, thick disk, halo, bulge) shows abundance patterns of elements from lithium to uranium. Trends in [α/Fe], [C/N], and neutron-capture ratios (e.g., [Ba/Eu]) track the relative contributions of core-collapse supernovae, Type Ia supernovae, AGB stars, and r-process events over time. Similar techniques applied to H II regions and damped Lyman-α systems probe the ISM and distant galaxies, linking nucleosynthesis to star formation histories.

Presolar Grains and Isotopic Anomalies

Presolar grains embedded in primitive meteorites retain isotopic ratios unlike bulk solar system matter. Analysis of silicon carbide, graphite, and oxide grains reveals signatures of s-process enrichments, supernova mixing, and nova contributions. These grains serve as direct samples of stellar ejecta and validate key aspects of nucleosynthesis models.

Each of these observational pillars reinforces the theoretical framework laid out in hydrogen burning, helium burning, advanced burning stages, and supernovae, while also providing constraints that guide improvements discussed in Modeling Challenges.

Chemical Evolution of Galaxies: From Population III to the Present Milky Way

Galactic chemical evolution (GCE) models connect stellar nucleosynthesis to the observed abundances in galaxies by tracking how gas is enriched over time by different stellar sources. Key ingredients include star formation rates, initial mass functions (IMFs), inflows and outflows of gas, and the yields and delay times of various enrichment channels.

Population III and Metal-Poor Stars

The first stars—Population III—formed from pristine gas composed almost entirely of hydrogen and helium with trace amounts of lithium. Although no Pop III star has been observed directly, extremely metal-poor stars in the Milky Way halo preserve chemical fossils of early nucleosynthesis. Their abundance patterns provide clues about the masses and explosion energies of the first supernovae and about the onset of r-process enrichment. Some metal-poor stars show strong enhancements in r-process elements, indicating early, possibly rare, events that seeded the halo with heavy elements.

[α/Fe] and the Supernova Clock

In the Milky Way disk, [α/Fe] ratios as a function of metallicity track the relative timing of core-collapse and Type Ia supernovae. Core-collapse supernovae, arising promptly after massive star formation, enrich the interstellar medium with α-elements (O, Mg, Si, S, Ca). After a delay set by binary evolution, Type Ia supernovae add iron-peak elements, decreasing [α/Fe]. This pattern appears consistently across many stellar populations and is a cornerstone test for GCE models.

AGB and r-Process Contributions Over Time

AGB stars contribute s-process elements on timescales of hundreds of millions to a few billion years, while r-process enrichment from neutron star mergers depends on the distributions of merger delay times and event rates. Reconciling the observed scatter in heavy-element abundances at low metallicities with event frequencies and yields remains an active topic. The timing of these contributors feeds back into constraints for r-process sites and for AGB nucleosynthesis models in the s-process.

Together, these observations weave a coherent narrative in which stellar evolution, feedback, and galaxy dynamics shape the chemical composition of stars and planets over cosmic time.

Big Bang Nucleosynthesis vs. Stellar Nucleosynthesis: Who Made What?

Not all elements come from stars. Big Bang nucleosynthesis (BBN) took place within the first few minutes after the Big Bang, when the universe was hot and dense enough for nuclear reactions to occur. BBN produced most of the universe’s 1H and 4He, with trace amounts of deuterium, 3He, and lithium. Heavier elements were not built in significant quantities during BBN because the rapidly expanding, cooling universe lacked the conditions for sustained fusion beyond these light nuclei.

Stellar nucleosynthesis, by contrast, operates over stellar lifetimes, reaching much higher densities and temperatures in stellar cores and explosive sites. It is responsible for carbon, oxygen, and virtually all elements heavier than lithium. Observations of deuterium in high-redshift gas clouds, helium in H II regions, and the cosmic microwave background all support the standard BBN predictions, while the distributions of heavier elements in galaxies reflect stellar processes described in hydrogen burning, helium burning, advanced burning, and supernovae.

One long-standing issue concerns primordial lithium: the “lithium problem” refers to the discrepancy between BBN predictions and the lower lithium abundances measured in some old stars. This is an area of ongoing research involving nuclear rates, stellar surface depletion, and observational systematics.

Nuclear Reaction Rates, the Gamow Peak, and Neutrino Physics

Accurate nucleosynthesis models depend critically on nuclear reaction rates and particle physics inputs. Rates at stellar energies are challenging to measure because cross sections can be extremely small, requiring underground laboratories and indirect methods.

The Gamow Peak and Stellar Energies

Fusion reactions in stars occur in a narrow energy window known as the Gamow peak, where the product of the Maxwell–Boltzmann velocity distribution and the quantum tunneling probability is maximized. The Gamow window shifts to higher energies with increasing temperature, enabling successive burning stages. Determining cross sections within this window—especially for reactions like ¹²C(α,γ)¹⁶O—is essential for reliable abundance predictions.

Electron Screening and Plasma Effects

In stellar interiors, free electrons partially shield nuclei from each other, modifying effective reaction rates compared to laboratory measurements. Quantifying these screening effects requires plasma physics and can influence the inferred core temperatures and energy generation, especially in lower-temperature regimes like the solar core.

Neutrino Transport and Opacities

In core-collapse supernovae and neutron star mergers, neutrinos dominate energy transport. Detailed neutrino–matter interactions—absorption, scattering, and the role of weak magnetism—affect the electron fraction of ejecta and thus nucleosynthetic yields. Modern simulations increasingly rely on multidimensional neutrino radiation hydrodynamics to model these processes accurately. The impact on the final abundance pattern ties back to explosive nucleosynthesis and r-process outcomes.

What We Don’t Yet Know: Modeling Challenges and Nuclear Physics Uncertainties

Despite major progress, stellar nucleosynthesis involves uncertainties that propagate into predictions for elemental yields and galactic evolution.

- Nuclear reaction rates: Extrapolating cross sections to stellar energies remains a source of uncertainty for key reactions like

¹²C(α,γ)¹⁶O,¹³C(α,n)¹⁶O, and²²Ne(α,n)²⁵Mg. Uncertainties at branching points in the s-process affect abundances of isotopes near magic neutron numbers. - Stellar mixing and rotation: Convection, overshoot, rotation, and magnetic fields transport chemical species and angular momentum. In AGB stars, the formation and size of the 13C pocket are crucial but not yet uniquely determined. In massive stars, rotation can induce mixing that alters pre-supernova structure and yields.

- Mass loss: Stellar winds in massive stars and AGB stars remove material and expose deeper layers. The rates depend on metallicity and stellar parameters, influencing the composition returned to the interstellar medium.

- Binary interactions: Many stars are in binaries. Mass transfer, common-envelope evolution, and mergers alter stellar evolution pathways and can trigger events like Type Ia supernovae. These interactions affect the timing and composition of enrichment.

- Explosion mechanisms: In core-collapse supernovae, the exact mechanism and conditions of shock revival determine which layers are ejected and how much fallback occurs. This strongly impacts predicted yields of iron-peak and intermediate-mass elements.

- Event rates and delay times: For r-process sources, the frequency of neutron star mergers and their delay-time distributions are active research areas. Reconciling them with observed heavy-element abundances at low metallicity is a key test for models.

These uncertainties underscore the importance of cross-disciplinary work between nuclear experiment, theory, and astrophysical observation, backed by advances in laboratory measurements, telescopes, and computational modeling. As constraints sharpen, they will refine the big-picture trends described in galactic chemical evolution and help resolve tensions like the lithium problem.

Frequently Asked Questions

Do stars make gold and platinum?

Yes, but not in ordinary stellar cores. The heaviest elements like gold and platinum are primarily synthesized by the rapid neutron-capture (r-) process, which occurs in environments with extremely high neutron densities. Current evidence points to neutron star mergers as major r-process sites, based on gravitational-wave detections and the electromagnetic signatures of kilonovae. Some rare types of core-collapse supernovae or collapsars may contribute, particularly for lighter r-process elements, but the relative contributions are an area of ongoing research.

Why do stars stop fusing elements at iron?

Fusion releases energy only when it produces nuclei with higher binding energy per nucleon. This quantity peaks around iron and nickel. Beyond iron, fusion becomes endothermic—it requires energy input rather than releasing it. When a massive star’s core composition approaches the iron peak, fusion can no longer support the core against gravity. Electron captures reduce pressure, the core collapses, and the star may explode as a core-collapse supernova, ejecting its outer layers and freshly synthesized elements.

Final Thoughts on Understanding Stellar Nucleosynthesis

Stellar nucleosynthesis weaves together nuclear physics, stellar evolution, and galactic dynamics to explain the origin of the elements. Beginning with hydrogen burning and progressing through helium burning and advanced fusion stages, stars build the periodic table up to the iron peak. Explosive nucleosynthesis and neutron-rich environments extend synthesis to the heaviest elements, while AGB stars quietly assemble many nuclei in between. Observations—from solar neutrinos to stellar and interstellar spectroscopy—continue to validate and refine this picture, even as open questions about reaction rates, mixing, and event rates motivate further research.

If you are exploring astrophysics or building models of cosmic chemical evolution, the key takeaways are clear: match stellar processes to their observational signatures; incorporate uncertainties in reaction rates and mixing; and connect enrichment channels to galaxy formation histories. Stay tuned for more deep dives into the physics behind the cosmos, and consider subscribing to our newsletter to receive upcoming articles on related topics, from stellar evolution to the chemistry of planetary systems.