Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Venus at a Glance

- Atmosphere and Climate Dynamics

- Surface and Geology

- Interior and Magnetism

- Missions: Past, Present, and Future

- Chemistry, Clouds, and Biosignatures?

- Observing Venus from Earth

- Data, Models, and Open Questions

- FAQs: Venus Science

- FAQs: Missions and Observing

- Conclusion

Introduction

Venus is Earth’s near twin in size and bulk composition, yet it hosts a world utterly transformed: an atmosphere ~92 times denser than Earth’s, temperatures hot enough to melt lead, and sulfuric acid clouds hiding a surface remade by volcanism. Understanding Venus is essential to understanding terrestrial planets—how they gain and lose atmospheres, how climates stabilize or run away, and why some Earth-sized planets are temperate while others are infernos. As exoplanet discoveries pile up, many super-Earths and sub-Neptunes orbit close to their stars; Venus is our nearest laboratory for testing how rocky planets evolve under intense radiation and limited water.

This article synthesizes what we know—anchored in past and ongoing missions—and what we do not yet know about Venus’s super-rotating atmosphere, its volcanic history and suspected present-day activity, the geology of its enigmatic tesserae highlands, and the prospects for upcoming missions like NASA’s DAVINCI and VERITAS and ESA’s EnVision. Along the way we connect climate, chemistry, geology, and space physics, and point you to relevant sections—see Atmosphere and Climate Dynamics for circulation and cloud chemistry, and Surface and Geology for radar views and volcanism evidence.

Ultraviolet image of Venus’ clouds as seen by the Pioneer Venus Orbiter

Venus at a Glance

- Mean radius: ~6052 km (0.95 Earth radii)

- Mass: ~0.815 Earth masses; surface gravity ~8.87 m/s²

- Orbital period (year): 224.7 Earth days

- Rotation: retrograde; sidereal day ~243 Earth days; solar day ~116.75 Earth days

- Atmospheric pressure at surface: ~92 bar (≈ 9.2 MPa)

- Surface temperature: ~735 K (≈ 462 °C)

- Atmosphere: ~96.5% CO₂, ~3.5% N₂, trace SO₂, H₂O, CO, and others

- Clouds: concentrated H₂SO₄ aerosols (~48–70 km), unknown UV absorber in upper cloud deck

- Magnetic field: no global dynamo; induced magnetosphere from solar wind interaction

- Surface: basaltic plains, shield volcanoes, coronae, rifts; highland tesserae (e.g., Alpha Regio)

The juxtaposition of near-Earth size and alien environment makes Venus a keystone for comparative planetology. Its slow, retrograde rotation underpins the global super-rotation, while its dense carbon dioxide atmosphere drives the archetypal runaway greenhouse—important analogs for climate evolution on both Earth and exoplanets.

Atmosphere and Climate Dynamics

Composition and Layered Structure

Venus’s atmosphere is dominated by carbon dioxide (~96.5%), with nitrogen (~3.5%) as the main minor constituent. Trace gases include sulfur dioxide (SO₂), water vapor (H₂O), carbon monoxide (CO), hydrogen chloride (HCl), hydrogen fluoride (HF), and others. The vertical structure is stratified into a thick troposphere, a sulfuric acid cloud system, and upper atmosphere layers (mesosphere and thermosphere):

- Troposphere (~0–48 km): Extremely dense and hot; temperature decreases with altitude from ~735 K at the surface to ~360 K near the cloud base. Convection is vigorous in lower layers.

- Cloud decks (~48–70 km): Three main layers of H₂SO₄-H₂O aerosols; sulfur chemistry drives formation (SO₂ + H₂O → H₂SO₄ via photochemistry aloft). Near ~55 km, pressure is roughly 0.5–1 bar and temperatures approach room-like values, but the environment is desiccated and corrosive.

- Mesosphere/Thermosphere (~70–150+ km): Temperatures vary with solar activity; night-side airglow (e.g., O₂ 1.27 µm and NO) traces recombination of photolytic products transported by global circulation.

Sulfur dioxide is abundant below the clouds but depleted above, where ultraviolet photons break it down; long-term variability in cloud-top SO₂ has been observed by spacecraft, with implications for episodic volcanism as a replenishment source.

Super-rotation: Winds That Outrun the Planet

Venus’s atmosphere circles the planet in just ~4 Earth days at cloud-top altitudes, vastly outpacing the 243-day solid-body rotation. This super-rotation is one of the most striking dynamical features of any planetary atmosphere. Data from the Pioneer Venus mission, ESA’s Venus Express (2006–2014), and JAXA’s Akatsuki (inserted into orbit in 2015) show zonal winds of ~60–120 m/s at ~65–70 km altitude. The circulation is driven by a web of thermal tides, planetary-scale waves, and eddies that redistribute angular momentum from the surface and lower atmosphere upward and equatorward.

General circulation models (GCMs) that include solar heating, infrared cooling, cloud radiative feedbacks, and topographic wave drag can reproduce key aspects of super-rotation, though details depend on cloud microphysics and the infamous “unknown UV absorber” that modulates solar heating in the upper cloud deck. The

absence of a global magnetic field also shapes the upper atmosphere through solar wind interaction and ionospheric dynamics.

Clouds, Hazes, and the Unknown UV Absorber

The clouds of Venus are not water clouds like Earth’s but are dominated by sulfuric acid droplets. They are arranged in three layers: lower, middle, and upper clouds, with particle sizes and concentrations varying with height. Ultraviolet images reveal high-contrast dark and bright features that track dynamics—and an unidentified UV-absorbing substance concentrated at altitudes ~60–70 km. Proposed absorbers include ferric chloride (FeCl₃), elemental sulfur allotropes (S₈), and other sulfur-bearing species, but a definitive identification remains elusive. Pinning down this absorber matters because it strongly influences the atmospheric radiative balance and thus the vigor of super-rotation.

Akatsuki’s imaging and spectroscopy continue to map cloud morphology, thermal tides, and the characteristic double-eyed polar vortices encircled by a “cold collar.” Long-period variations in cloud-top winds and contrasts hint at coupled chemistry–dynamics feedbacks.

Runaway Greenhouse and Planetary Water Loss

Venus is the prototype for a runaway greenhouse. In the distant past, Venus may have possessed more water; today, water vapor is a trace constituent and the deuterium-to-hydrogen (D/H) ratio is strongly enriched relative to Earth’s, consistent with extensive hydrodynamic escape of hydrogen over geologic timescales. Without sufficient surface water and with rising solar luminosity, positive feedbacks (increased infrared opacity and reduced outgoing longwave radiation) likely drove the planet toward present conditions.

The heavy CO₂ atmosphere is excellent at trapping heat, and the sulfuric acid cloud layer adds complex radiative effects—both reflective in the shortwave and absorbing/emitting in the infrared. Modeling this climate requires accurate spectroscopic data for CO₂–CO₂ collision-induced absorption and cloud optical properties, topics that connect to data needs and modeling.

Electrodynamics and Lightning: What Do We Know?

Reports of lightning on Venus date back decades, including whistler-mode radio signatures and low-frequency electromagnetic waves measured by Soviet and later missions. Optical detections have been challenging due to cloud opacity. Some analyses suggest lightning is plausible, especially in convectively active regions near the cloud base where mixed-phase particles and charge separation could occur. However, unambiguous, repeated optical confirmation remains debated. Future dedicated instruments could settle the question. Electrical activity, if confirmed, would influence cloud microphysics, trace-gas chemistry, and potentially the vertical transport of aerosols noted in cloud chemistry.

Surface and Geology

Seeing Through the Clouds: Radar Mapping

Venus’s clouds are opaque to visible light, so surface observations rely on radar. NASA’s Magellan mission (1990–1994) mapped ~98% of the surface at ~100–300 m resolution with synthetic aperture radar (SAR). Radar brightness is influenced by surface roughness and dielectric properties, while altimetry provided global topography. The result is a world dominated by basaltic plains, with extensive volcanic features and tectonically deformed regions.

- Highlands: Ishtar Terra (with Maxwell Montes, the highest mountain) and Aphrodite Terra are elevated regions with complex deformation.

- Tesserae: Highly deformed, geologically complex terrains (e.g., Alpha Regio) with intersecting ridges and troughs, likely among the oldest surfaces on the planet.

- Volcanic plains: Vast lava plains dotted with shield volcanoes, lava flows, and distinctive features like pancake domes—thick, viscous flows possibly from more evolved magmas or high crystal content.

- Coronae: Circular to oval structures from mantle upwellings and lithospheric sagging, often hundreds of kilometers across (e.g., Artemis Corona).

These radar datasets anchor nearly all geologic interpretations and remain the reference baseline for detecting change, as highlighted in mission plans for interferometric SAR.

Volcanism: Past Abundance and Present Activity?

Volcanism is pervasive on Venus. Shield volcanoes, flow fields, and domes are widespread; coronae and rift systems suggest persistent mantle upwelling and lithospheric flexure. Crater counts indicate a relative youthfulness (average surface age on the order of hundreds of millions of years), implying extensive resurfacing. Whether resurfacing occurred catastrophically or more continuously is debated.

Multiple lines of evidence point to ongoing or recent activity:

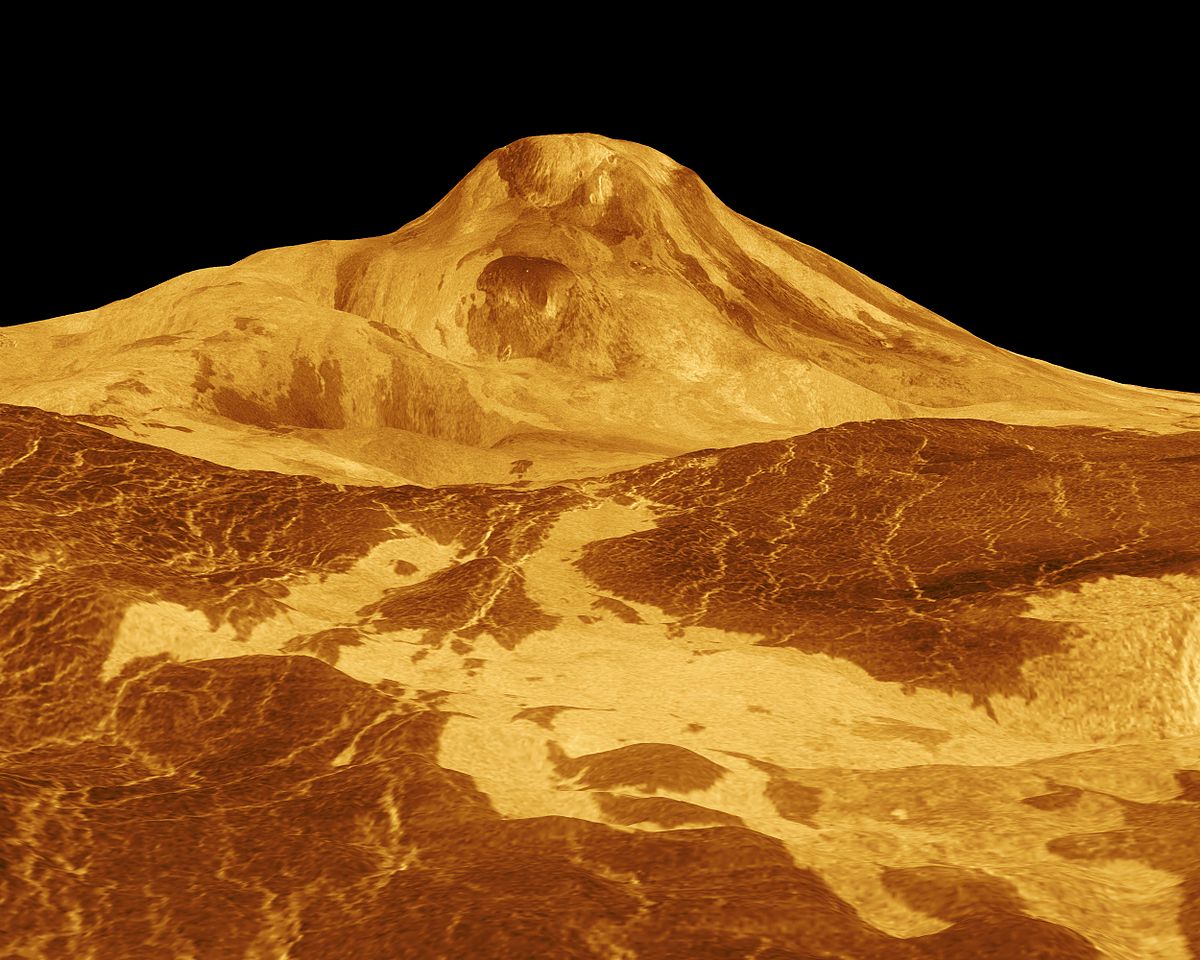

- Change detection in radar: Reanalysis of Magellan data has identified temporal changes suggestive of new or modified volcanic vents in the Maat Mons region, consistent with eruptions between mapping cycles.

- SO₂ variability: Measured decadal variations in cloud-top SO₂ by spacecraft may reflect episodic volcanic injections balanced by photochemical loss; alternative dynamical explanations exist, making this an open problem.

- Thermal emissivity anomalies: Near-infrared “windows” on the night side allow limited probing of the surface emissivity; variations have been interpreted as differences in rock freshness or composition, possibly tied to volcanism.

Upcoming missions will directly target change detection and thermal anomalies (see Missions) to confirm whether Venus is geologically active today.

Cratering, Resurfacing, and Geologic Timescales

Venus’s thick atmosphere filters out small meteoroids; most craters are larger than ~3 km and display distinctive features like parabolic ejecta deposits formed by shock-induced fragmentation producing high-altitude ejecta plumes. The relatively uniform distribution of ~1000 identified impact craters suggests the surface has been globally resurfaced within the last ~300–700 million years. Mechanisms proposed include episodic global volcanic resurfacing or steady, spatially heterogeneous volcanism with burial of older terrains.

Discriminating between these scenarios will benefit from improved crater catalogs, better stratigraphic relationships resolved by higher-resolution radar, and potentially radiometric ages if future missions can sample or in situ-date rocks—a formidable challenge given the environment discussed in Atmosphere and Climate.

Tesserae: What Are They Made Of?

Tesserae are among the most intriguing terrains on Venus—intensely deformed highlands with cross-cutting ridges and troughs, thought to be older than surrounding plains. Their composition is uncertain. Some interpretations of near-infrared emissivity suggest they may be more silica-rich than the plains, potentially akin to continental crustal materials formed by extensive alteration or differentiation. Others argue for basaltic compositions modified by weathering or metamorphism under Venusian conditions.

Resolving tessera composition and formation mechanisms is central to understanding whether Venus ever experienced processes analogous to proto-plate tectonics or long-lived crustal differentiation. NASA’s DAVINCI will image Alpha Regio during descent and measure key atmospheric gases that constrain past water inventories relevant to crust formation.

Interior and Magnetism

Interior Structure and Heat Flow

Venus’s bulk composition is similar to Earth’s, with an iron-rich core, silicate mantle, and crust. The core is likely at least partially liquid, but the planet lacks a detectable global magnetic field. Heat loss is dominated by conduction and volcanism rather than plate tectonics. Lithospheric thickness, mantle convection style (stagnant lid vs. episodic overturn), and bulk volatile content remain areas of active research.

Gravity and topography correlations suggest mantle dynamic support of highlands (e.g., Ishtar and Aphrodite Terra). The abundance of volcanic and tectonic features indicates substantial interior activity, consistent with the resurfacing record outlined in Surface and Geology.

Why No Global Dynamo?

A functioning planetary dynamo requires convective motions in an electrically conducting fluid region (like Earth’s outer core). Venus’s lack of a dynamo may be due to a combination of slow rotation, thermal stratification, and limited core cooling if the mantle’s stagnant lid impedes efficient heat loss. The precise balance of factors is still debated. Without a dynamo, Venus’s interaction with the solar wind creates an induced magnetosphere and magnetotail.

Induced Magnetosphere and Atmospheric Escape

Venus’s ionosphere couples to the solar wind, generating a bow shock and induced magnetotail. Ion pickup and sputtering processes lead to escape of atmospheric constituents. Measurements of heavy isotope enrichments (e.g., D/H) indicate significant water loss over time. Venus Express provided key in situ measurements of ion escape pathways, complementing remote sensing of upper-atmospheric composition discussed in Atmosphere.

Missions: Past, Present, and Future

Foundational Era: Venera, Vega, and Pioneer Venus

The Soviet Venera landers (1970–1982) and Vega balloons (1985) transformed Venus science. Venera landers returned the first surface images and chemical analyses before succumbing to extreme temperatures and pressures (survival times were typically under two hours). The Vega balloons floated at ~54 km altitude for about two days, measuring winds and atmospheric properties in the temperate but corrosive middle cloud layer. NASA’s Pioneer Venus mission (1978) delivered both an orbiter (mapping clouds and upper atmosphere) and multiprobe in situ measurements, anchoring our understanding of vertical structure and composition.

Global Radar Revolution: Magellan

NASA’s Magellan (1990–1994) mapped the surface with synthetic aperture radar and altimetry, providing the geologic framework used to this day. Its data underpin our knowledge of plains, tesserae, coronae, rifts, and volcanoes, and enable the change-detection work that hints at recent volcanism.

Climate and Escape: Venus Express

ESA’s Venus Express (2006–2014) focused on atmosphere, climate, and plasma environment. It observed SO₂ variability, tracked winds, characterized the double-eyed polar vortex, measured night-side airglow, and quantified ion escape. These results refined models of super-rotation and upper-atmospheric chemistry.

Clouds and Waves: Akatsuki

After an initial insertion failure in 2010, JAXA’s Akatsuki successfully entered Venus orbit in 2015. Its multiwavelength imaging targets cloud morphology, thermal tides, and planetary-scale gravity waves. Akatsuki continues to provide critical context for circulation and cloud microphysics, feeding into the questions raised in cloud chemistry and modeling.

Flybys and Serendipity: Parker Solar Probe, BepiColombo, Solar Orbiter

Several missions en route to other destinations have flown by Venus, gathering valuable data. NASA’s Parker Solar Probe has imaged the night side in infrared bands and sampled the plasma environment during gravity assists. ESA/JAXA’s BepiColombo and ESA/NASA’s Solar Orbiter also executed flybys, contributing to atmosphere–solar wind interaction studies and providing opportunistic imaging and field measurements.

On the Horizon: DAVINCI, VERITAS, and EnVision

A renaissance in Venus exploration is planned:

- NASA’s DAVINCI (Deep Atmosphere Venus Investigation of Noble gases, Chemistry, and Imaging): An atmospheric entry probe with a carrier/relay spacecraft. The probe will make high-precision measurements of noble gases and isotopes (e.g., argon, neon, xenon; D/H) to constrain Venus’s origin, water history, and atmospheric evolution. It will image tesserae (Alpha Regio) during descent and profile temperature, pressure, and composition from the upper atmosphere to the surface.

- NASA’s VERITAS (Venus Emissivity, Radio Science, InSAR, Topography, and Spectroscopy): A global mapping mission using interferometric SAR and near-infrared spectroscopy to produce high-resolution topography and surface emissivity maps. Objectives include tectonic and volcanic processes, resurfacing history, and active change detection. VERITAS has experienced schedule delays; its capabilities are designed to far surpass Magellan.

- ESA’s EnVision: A complementary orbiter carrying a suite that includes high-resolution SAR, subsurface sounding, and spectrometers. EnVision aims to link interior processes to surface geology and atmospheric signatures, targeting volcanism, tesserae, and volatile cycles.

Together, these missions are poised to answer whether Venus is active now, how its crust and mantle exchange volatiles, and how its climate has evolved—a triad of questions intertwined across geology, climate, and interior dynamics.

Chemistry, Clouds, and Biosignatures?

Phosphine Controversy: A Case Study in Scientific Process

In 2020, a claim of phosphine (PH₃) detection in Venus’s clouds ignited excitement because, on Earth, phosphine is associated with both industrial processes and certain microbial environments. Subsequent reanalyses questioned the initial spectral interpretation, suggesting that the observed lines may be attributable to sulfur dioxide and that the inferred abundances were inconsistent with other constraints. As of 2024, there is no consensus detection of phosphine at the tens-of-parts-per-billion levels originally reported. Upper limits from multiple facilities and analyses have tightened, and the community continues to refine calibrations and retrieval methods.

This episode underscores how challenging remote sensing in the presence of strong, overlapping lines and instrument systematics can be. It also invigorated proposals for targeted in situ measurements—one of the motivations for future probes discussed in Missions.

Sulfur Chemistry and Aerosols

Above the cloud base, photochemistry steadily converts SO₂ and H₂O into H₂SO₄ aerosols, which coagulate and sediment. Below the cloud base, sulfur species can be abundant and may undergo heterogeneous reactions with surface minerals and dust. The vertical distribution of SO₂ is highly sensitive to dynamics and volcanic outgassing. Cloud particle size distributions (often parameterized as modes) control scattering and absorption across wavelengths, impacting the radiative energy budget and thus the circulation.

Habitability at the Cloud Deck?

Around ~50–60 km altitude, pressure is near Earth sea level and temperatures are in the range comfortable for life as we know it. However, the clouds are composed of concentrated sulfuric acid with very little water, a hostile environment for terrestrial organisms. While speculative astrobiology has considered whether extremophile-like life could persist in such aerosols, current knowledge offers no evidence for biology. Nonetheless, life-independent disequilibria (e.g., redox or sulfur cycle imbalances) are scientifically valuable clues to climate and chemistry. In situ instruments that can analyze aerosol composition and microphysics would help answer these questions.

Observing Venus from Earth

Naked Eye and Telescopic Views

Venus is the brightest planet in our sky, visible as the “evening star” or “morning star.” Its high albedo and proximity to Earth make it dazzlingly bright, with phases like the Moon (crescent to gibbous) as it orbits the Sun interior to Earth. Telescopically, observers can track its phases and changing apparent diameter. Surface details are invisible in visible light due to clouds, but ultraviolet filters can reveal cloud contrasts. Always use proper solar avoidance techniques—never observe Venus near the Sun without adequate safety margins.

Thermal and Near-IR Windows

Near-infrared “windows” on the night side (around 1 µm and longer wavelengths) permit limited probing of cloud opacity and surface emissivity. Professional observatories and spacecraft exploit these windows to map lower clouds and detect potential thermal anomalies that may correlate with fresh volcanic flows. Amateur access to these bands is limited but growing with specialized filters and cameras.

Radar Observations and Planetary Spin

Ground-based radar (e.g., Goldstone and former Arecibo), often using bistatic configurations, has been used to measure Venus’s rotation rate and surface reflectivity. Repeated measurements show small but measurable differences in apparent rotation rate over time, likely due to exchange of angular momentum between the super-rotating atmosphere and the solid planet. These studies complement spacecraft radar mapping and inform models of atmosphere–interior coupling.

Data, Models, and Open Questions

Climate and Dynamics Modeling

Venus general circulation models aim to reproduce super-rotation, thermal structure, cloud distributions, and diurnal tides. Key sensitivities include cloud microphysics, radiative properties (including the unknown UV absorber), and surface–atmosphere momentum exchange over a rough, high-pressure lower atmosphere. Data assimilation efforts with Akatsuki imagery are improving wind fields and wave characterization. The interplay between planetary-scale waves and mean flow maintenance is an area of active study with implications for circulation.

Geodynamic Scenarios

Geophysical models explore stagnant-lid convection, episodic overturn, and localized lithospheric weakening to account for Venus’s geology and resurfacing history. Coronae may trace mantle plumes or diapirs interacting with a stiff lithosphere; tesserae may represent regions of thickened crust or complex strain histories. Heat flow estimates are indirect, relying on gravity-topography relationships and modeling since in situ heat-flow data are unavailable. VERITAS and EnVision’s topography and subsurface sounding should help discriminate among models of resurfacing and lithospheric rheology.

High-Temperature Materials and Instrumentation

Venus’s surface environment challenges electronics and materials: 735 K, 92 bar, and reactive gases. Progress in high-temperature semiconductors (e.g., SiC) and robust thermal protection (e.g., high-enthalpy entry systems) will expand mission envelopes. Balloons offer a comparatively benign environment at ~55 km, as demonstrated by the 1985 Vega balloons, enabling prolonged sampling of the middle cloud region.

Open Questions

- Is Venus volcanically active today? If so, at what rate and where?

- What is the composition and formation history of tesserae?

- What species constitute the unknown UV absorber, and how does it modulate climate?

- How did Venus lose its water, and what were the timelines and processes?

- What maintains super-rotation quantitatively, and how variable is it over decades?

- How strongly do atmosphere and solid-body exchange angular momentum and heat?

- Is there lightning? What is its frequency and impact on chemistry?

FAQs: Venus Science

Is Venus’s surface really uniformly young?

Crater statistics suggest a relatively young average surface age (hundreds of millions of years) and a near-random crater distribution. However, “uniformly young” oversimplifies the picture. Some terrains—like tesserae—are likely older, and volcanic plains may include flows of different ages. Higher-resolution radar and stratigraphic analyses are needed to map age relationships in detail. Change-detection and thermal emissivity measurements from future missions will refine resurfacing rates discussed in Surface and Geology.

Could Venus ever have had oceans?

It is plausible that Venus once had more water, potentially including shallow oceans, especially earlier in Solar System history when the Sun was dimmer. The enriched D/H ratio indicates significant water loss. Whether Venus experienced long-lived oceans or only transient, warm intervals depends on initial water inventory, outgassing rates, and cloud feedbacks. High-precision noble gas and isotope data from DAVINCI will constrain the early water budget.

Why does Venus rotate so slowly and retrograde?

Venus’s slow, retrograde rotation may reflect a complex combination of early spin-state evolution, giant impacts, and long-term tidal torques with the Sun’s gravitational field acting on the dense atmosphere and solid planet. Atmospheric tides can exchange angular momentum with the solid body, potentially modifying the rotation rate, consistent with radar observations of small variability described in Observing Venus.

What are coronae and how do they form?

Coronae are circular-to-oval features thought to form from mantle upwellings (diapirs) that domed and fractured the lithosphere, followed by sagging and magmatic intrusions. Their occurrence across Venus suggests widespread mantle dynamics under a stagnant-lid regime. VERITAS and EnVision data should clarify subsurface structures and sequences, informing geodynamic models.

Is phosphine on Venus a closed case?

As of 2024, there is no robust, widely accepted detection of phosphine in Venus’s atmosphere at the initially reported levels. Improved analyses and independent observations have placed tighter upper limits. The episode has catalyzed interest in targeted, in situ cloud measurements that could directly test for PH₃ and other reduced species. See Chemistry, Clouds, and Biosignatures? for context.

FAQs: Missions and Observing

How will VERITAS improve on Magellan?

VERITAS will deploy modern interferometric SAR to achieve higher spatial resolution and repeat-pass coverage enabling topographic precision and surface deformation studies. Its near-infrared spectrometer will map surface emissivity and detect rock compositional differences. Compared to Magellan’s early-1990s technology, VERITAS’s instruments provide sharper imaging, better radiometry, and geodetic-quality topography—crucial for detecting active change and characterizing volcanism and tectonics.

What will DAVINCI measure that we don’t already know?

DAVINCI’s probe will deliver laboratory-grade measurements of noble gases (He, Ne, Ar, Kr, Xe) and isotopic ratios (e.g., D/H, ³⁶Ar/³⁸Ar, ¹²C/¹³C) with far higher precision than previous missions. These data constrain Venus’s origin, degassing history, and water inventory. The probe will also sample and profile trace gases (SO₂, H₂O, CO) across altitudes, image tessera terrain during descent, and provide a modern vertical context that connects to climate and geology.

When will we know if Venus is erupting now?

Definitive confirmation requires repeat imaging capable of detecting new flows, thermal anomalies, or gas plumes. VERITAS and EnVision aim to provide such datasets in the 2030s, while continued reanalysis of Magellan and ground-based thermal/IR work may reveal additional hints. Cloud-top SO₂ variability and near-IR emissivity windows are suggestive but not yet conclusive; a combination of radar change detection and spectroscopic gas measurements will be the clinchers.

Can amateurs contribute to Venus science?

Yes. Amateur observations in ultraviolet can track cloud patterns and provide long-term monitoring complementary to spacecraft. Coordinated campaigns during elongations help fill time gaps. While professional facilities dominate radar and near-IR work, well-calibrated amateur UV imaging can inform studies of wind speeds and cloud morphologies when combined with spacecraft data.

Conclusion

Venus is at once familiar and alien: an Earth-sized world with a climate and geology that push the limits of what rocky planets can be. Its super-rotating, sulfuric-acid clouded atmosphere embodies the runaway greenhouse endmember; its surface displays the scars of vast volcanism, enigmatic tesserae, and a resurfacing history that defies simple narratives. The lack of a global magnetic field, the induced magnetosphere, and the planet’s rich sulfur chemistry entwine atmosphere and space environment in ways central to planetary evolution.

A new era of exploration—DAVINCI’s deep dive, VERITAS’s radar and emissivity maps, and EnVision’s complementary views—promises to transform our understanding. These missions will tackle the biggest questions raised in geology, climate dynamics, and interior physics. For observers on Earth, Venus will continue to be the brilliant herald of dawn or dusk—an ever-present reminder that the fates of Earth-like worlds can diverge dramatically.

If you enjoyed this deep dive, explore related topics in our archive—from atmospheric physics to comparative planetology—and consider subscribing for updates as the next generation of Venus missions approaches.