Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Titan at a Glance

- Atmosphere and the Methane Cycle

- Surface, Dunes, and Geology

- Lakes and Seas: Kraken, Ligeia, and Punga

- Interior Structure and Subsurface Ocean

- Weather, Clouds, and Seasons

- Organic Chemistry and Haze Formation

- Magnetosphere and Plasma Interaction

- Missions and Key Discoveries

- Dragonfly: The Rotorcraft Lander

- Observing Titan from Earth

- Data Resources and Tools

- FAQs

- Advanced FAQs

- Conclusion

Introduction

Titan, Saturn’s largest moon, is a world of superlatives: the only moon with a thick atmosphere, the only place beyond Earth with stable bodies of liquid on its surface, and one of the most chemically complex environments in the Solar System. Its nitrogen-rich air, methane weather, dunes of organic “sand,” and lakes of liquid hydrocarbons make Titan a natural laboratory for studying prebiotic chemistry and climate processes that mirror Earth’s hydrologic cycle in slow motion at cryogenic temperatures.

Thanks to the Cassini–Huygens mission, we now have a multi-decade foundation of data about Titan’s atmosphere, surface, and interior. The coming Dragonfly rotorcraft mission will expand that legacy by sampling the surface in multiple locations and analyzing organic molecules in situ. This article synthesizes what is known—and still unknown—about Titan’s methane cycle, geology, interior ocean, and habitability potential, and it provides practical guidance for observers who want to tease Titan’s disk from Earth-based optics.

If you’re new to Titan, start with Titan at a Glance. Readers interested in habitability and astrobiology may want to jump to Interior Structure and Subsurface Ocean and Organic Chemistry and Haze Formation. For mission plans and instruments, see Dragonfly, and for practical tips on seeing Titan visually and with cameras, see Observing Titan from Earth.

Titan at a Glance

Titan is the second-largest moon in the Solar System, slightly smaller than Jupiter’s Ganymede but larger than the planet Mercury. Its bulk properties are:

- Mean radius: ~2,575 km (diameter ~5,150 km)

- Mass: ~1.345 × 1023 kg

- Mean density: ~1.88 g/cm3

- Surface gravity: ~1.35 m/s2 (~14% of Earth’s)

- Surface pressure: ~1.5 bar (denser than Earth’s at sea level)

- Surface temperature: ~94 K (-179 °C)

- Composition: water-ice crust and lithosphere, likely global subsurface ocean, rock-ice interior

- Orbit around Saturn: semi-major axis ~1.22 million km; period ~15.95 Earth days (synchronous rotation)

- Atmosphere: ~98% nitrogen, with methane and trace hydrocarbons and nitriles

As an analog system, Titan provides a rare opportunity to compare Earth’s hydrologic cycle with a hydrocarbon cycle—methane and ethane stand in for water, and organic solids (tholins) likely constitute windblown “sand.” Its seasons are long, tracking Saturn’s ~29.5-year revolution around the Sun, making Titan’s meteorology a slow but revealing experiment in planetary climatology. For a deep dive into Titan’s climate, see Weather, Clouds, and Seasons.

Atmosphere and the Methane Cycle

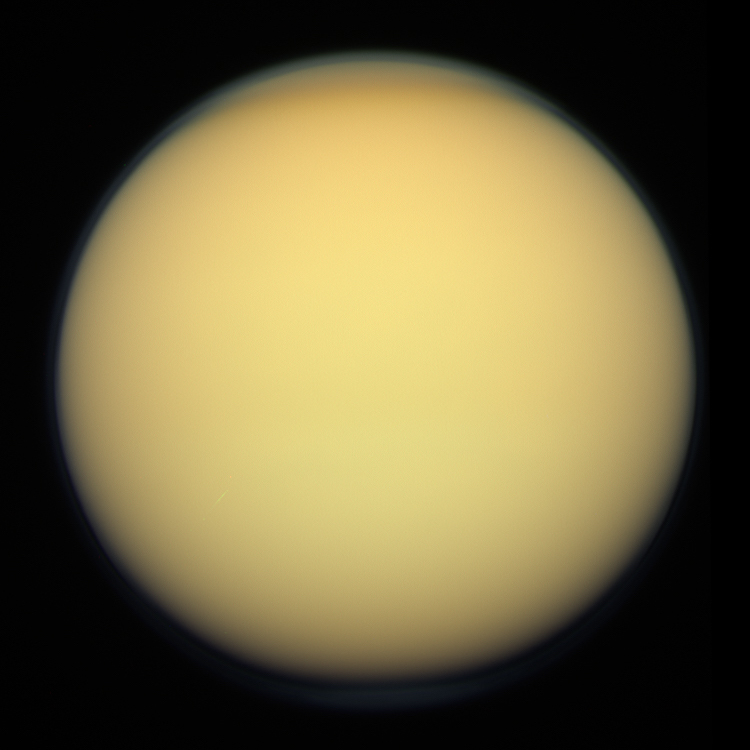

Titan’s atmosphere is dominated by nitrogen (N2) and enriched with methane (CH4) at percent-level abundance. Trace species include ethane (C2H6), acetylene (C2H2), hydrogen cyanide (HCN), and a zoo of hydrocarbons, nitriles, and complex ions. High in the atmosphere, solar ultraviolet photons and energetic particles break apart methane and nitrogen molecules. The resulting radicals and ions recombine to form progressively heavier organics, eventually yielding the orange smog of complex hydrocarbons and nitriles—tholins—that gives Titan its characteristic hue.

The methane cycle resembles Earth’s hydrology:

- Evaporation and humidity: Methane and ethane evaporate from lakes and seas, increasing atmospheric humidity, especially near the poles.

- Cloud formation: Condensation at cold-altitude layers produces methane clouds. Ethane and other species can also condense under appropriate conditions.

- Rain: Cassini observed methane rain and transient darkening events interpreted as wetting of the surface—evidence of fluvial processes today.

- Runoff and infiltration: Channel networks sculpt uplands and carry debris (likely water-ice clasts) onto plains and into seas.

- Reservoirs: Polar seas (see Lakes and Seas) and porous sediments act as sinks and long-lived stores.

But there is a key twist: methane is unstable over geologic timescales under steady photolysis. Without replenishment, models indicate Titan’s atmospheric methane would disappear in roughly 10–100 million years. Therefore, Titan’s methane must be resupplied, or the current epoch is transient. Candidate sources include outgassing from clathrate hydrates in the crust, cryovolcanism (possible but debated; see Surface, Dunes, and Geology), and conversion/reprocessing via subsurface reservoirs.

Huygens directly measured a moist lower atmosphere with methane humidity varying with altitude, while Cassini’s instruments sampled a rich inventory of photochemical products aloft. Together they reveal an atmosphere in chemical disequilibrium that demands an active methane cycle.

Vertical structure and winds

The troposphere extends to about 40–50 km altitude, capped by a tropopause near 70 K. Above lies a stratified stratosphere and mesosphere with temperature inversions and photochemical hazes. Superrotation—eastward winds faster than the moon’s rotation—occurs in the stratosphere, similar in concept to Venus but driven by Titan’s unique thermal tides and haze heating. Near the surface, winds are modest but capable of mobilizing sand-sized particles under seasonally enhanced conditions (see Surface, Dunes, and Geology).

Timescales and transport

Titan’s long seasons slow the hydrologic analog: cloud outbreaks may cluster near equinoxes, with polar regions hosting persistent lakes and fogs during their respective winters. Global circulation transports photochemical products toward the winter pole, where subsidence can concentrate trace gases and form polar hoods. Methane lifetime versus transport implies multi-year to multi-decade storage and exchange between atmosphere, surface liquids, and subsurface reservoirs.

Surface, Dunes, and Geology

Titan’s surface is a patchwork of bright uplands (likely water-ice bedrock or heavily processed icy terrains), vast dark equatorial plains mantled by dunes, dissected fluvial networks, labyrinth terrains, and polar basins hosting lakes and seas. Cassini’s radar Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR) and near-infrared imaging pierced the haze to map these terrains at regional to local scales.

- Dune seas: Linear dunes hundreds of meters high and kilometers long girdle the equator, forming fields that stretch for thousands of kilometers. The “sand” grains are thought to be organic solids—products of atmospheric chemistry—possibly mixed with water-ice. Dune orientations encode wind regimes influenced by Titan’s seasonal cycle and topography.

- Fluvial networks: Branched valleys and channels cut bright uplands and dark plains, converging toward basins and seas. Rounded cobbles imaged by Huygens indicate sustained or repeated liquid flow capable of mechanical weathering.

- Mountains and tectonics: Ridges and mountain belts rise up to ~1 km. Global tectonics appear subdued compared to Earth, but faults, compressional features, and possible cryovolcanic constructs are present in places.

- Labyrinth terrain: Highly dissected uplands with maze-like valleys may reflect intense dissolution, erosion by rainfall, or structural controls in friable material.

Huygens touched down on January 14, 2005, near the boundary between bright uplands and darker plains, imaging a landscape of channels, elevated islands, and a pebbly, damp surface. Spectral readings showed the “pebbles” are consistent with water-ice, and near-surface methane humidity suggested the ground had recently interacted with liquid.

Is cryovolcanism active?

Cryovolcanism—eruption of water-ammonia or other volatiles—has been proposed to explain certain features and to resupply atmospheric methane. Candidates include constructs such as Sotra Patera and lobate flow-like features seen in radar and infrared data. However, interpretations remain debated: many features can also be explained by tectonics, erosion, or sedimentary processes. As of now, there is suggestive but not definitive evidence for cryovolcanism. The question is central because it ties directly to the methane budget (see Atmosphere and the Methane Cycle) and to potential pathways for exchanging materials between the interior and surface (see Interior Structure and Subsurface Ocean).

Dune sands and sediment pathways

Dunes require adequate supply of sand-sized grains, wind to transport them, and areas of low relief to accumulate. Titan’s sand may form by aggregation of atmospheric aerosols into larger particles, by sintering of organic coatings onto ice cores, or by breakdown of larger organic deposits. The observed linear dunes imply a bidirectional wind regime with a seasonally oscillating component. Sediment pathways likely connect uplands (source of water-ice fragments and organics) to dry basins and dune fields, with episodic rainfalls reworking and concentrating materials.

Lakes and Seas: Kraken, Ligeia, and Punga

One of Titan’s signature discoveries is the presence of stable liquid reservoirs—lakes and seas—dominated by methane and ethane, with dissolved nitrogen and other species. These bodies cluster near the poles, with the northern hemisphere hosting the largest seas:

- Kraken Mare: The largest sea, spanning hundreds of kilometers, with complex shorelines and multiple basins. Depth sounding suggests portions are hundreds of meters deep.

- Ligeia Mare: A large, relatively deep sea—depths reaching on the order of ~160 meters have been inferred—thought to be methane-rich based on dielectric properties and composition analyses.

- Punga Mare: Smaller than Kraken and Ligeia but still a significant polar reservoir.

Radar altimetry and specular reflections (“glints”) measured the smoothness and elevation of liquid surfaces. Bathymetric inferences arise from radar absorption and reflectivity—liquids attenuate radar differently depending on composition and depth. Nearshore morphologies, dendritic inlets, and raised rims suggest complex shoreline evolution. Some lakes appear to occupy steep-sided depressions resembling karstic sinkholes on Earth, hinting that dissolution of organic deposits or ice-rich substrates shapes the landscape.

Waves, tides, and “magic islands”

Waves on Titan’s seas are typically subtle—centimeters or less—owing to low winds and the high viscosity/surface tension of hydrocarbon mixtures. Cassini nevertheless detected changes in radar backscatter and specular patterns that indicate wave activity at times. The famous “magic island” phenomena—ephemeral bright features—may be caused by transient wave fields, bubbles (e.g., nitrogen exsolution), floating solids, or evolving surface films. Tides from Saturn’s gravity should induce centimeter-scale sea level changes and currents, with magnitudes depending on sea geometry and the compliance of Titan’s crust.

Liquid chemistry

Composition varies among basins and with season. Ligeia appears relatively methane-rich, while other basins may be more ethane-enriched. Dissolved nitrogen and trace hydrocarbons influence density and stratification, potentially creating layered liquids in deep basins. Shoreline chemistry—including precipitated organics and evaporitic deposits—may record climate history in chemical “bathtub rings.” These environments are prime targets for astrobiology-inspired geochemistry (see Organic Chemistry and Haze Formation).

Interior Structure and Subsurface Ocean

Cassini gravity measurements, shape constraints, and tidal response indicate that Titan likely harbors a global subsurface ocean beneath an ice shell. Key points:

- Ice shell: Tens to perhaps over 100 km thick, overlying the ocean. Thickness may vary regionally.

- Ocean: Likely water with dissolved ammonia and salts acting as antifreeze, at depths of tens to hundreds of kilometers below the surface.

- Rocky core: Encloses most of Titan’s silicate mass; the core may be hydrated and could participate in long-term geochemical cycles.

The presence of an ocean is inferred from Titan’s response to Saturn’s tides—too large for a fully solid body—implying a decoupling layer. Electrical and thermal models are consistent with a saline, possibly convecting ocean. If fractures or cryovolcanic conduits occasionally connect the ocean to the surface, then oxidants and organics could exchange between reservoirs, with implications for habitability and methane resupply (linking back to Atmosphere and the Methane Cycle and Surface, Dunes, and Geology).

Habitability potential

Two distinct habitats are often discussed:

- Surface hydrocarbon liquids: Extremely cold, nonpolar solvents (methane/ethane). Conventional water-based life is unlikely here, but exotic chemistry may proceed at slow rates. Dragonfly’s analyses (see Dragonfly) will probe whether complex organics have assembled into prebiotic architectures.

- Subsurface ocean: Liquid water with antifreezes (ammonia/salts) could sustain aqueous chemistry more familiar to biology. If energy sources (e.g., tidal dissipation, radiolysis, water–rock reactions) are present, an oceanic biosphere is a speculative but testable possibility in the long term.

Even without life, Titan’s disequilibria—oxidants generated in the atmosphere versus reductants from the interior—create a powerful engine for geochemistry. Understanding whether and how these reservoirs communicate is central to Titan science in the Dragonfly era.

Weather, Clouds, and Seasons

Titan’s seasons unfold over decades. The northern summer solstice occurred in 2017, following an equinox in 2009; the system is gradually evolving toward the next seasonal milestones. Observations show:

- Cloud outbreaks preferentially near equinox times, with large convective systems capable of producing widespread precipitation.

- Polar hoods and vortices in winter hemispheres, where subsidence concentrates trace gases and haze layers.

- Fog and boundary-layer phenomena near liquids and lowlands, indicating active surface-atmosphere exchange.

A particularly notable event was a large equatorial cloud outburst and surface darkening observed during the Cassini mission, interpreted as rainfall and subsequent drainage. Seasonal migration of the Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ)-like band modulates where clouds and rain occur, shifting the focus of fluvial erosion and sediment transport. This seasonal hydrology helps explain why lakes and seas are strongly concentrated at high latitudes (see Lakes and Seas), while the equatorial zone is dry and dominated by dunes (see Surface, Dunes, and Geology).

Wind environment

Near-surface winds are generally weak—meters per second—but they can intensify during storm outflows or seasonal transitions. Dune orientations and occasional dark streaks in images imply that rare but strong winds episodically rework the equatorial sands. Aloft, stratospheric superrotation underscores a dynamic circulation influenced by haze heating and wave–mean flow interactions.

Organic Chemistry and Haze Formation

Titan’s orange haze is the visible manifestation of a deep and active photochemical reactor. Starting with N2 and CH4, ultraviolet photons and energetic particles drive a network of reactions that build up organic molecules from simple radicals to complex macromolecules. Key chemical families include:

- Hydrocarbons: Methane, ethane, acetylene, propane, benzene, and higher alkanes/alkenes/alkynes.

- Nitriles: Hydrogen cyanide (HCN), acetonitrile (CH3CN), and related species.

- Ions and macromolecules: Negative ions and high-mass species detected in the ionosphere suggest early stages of polymer formation.

These species aggregate into aerosol particles that evolve as they settle. By the time they reach the lower atmosphere and surface, they may form tholins, complex, tar-like organics that coat the landscape. Titan’s dunes likely incorporate such organics, while liquids dissolve and transport soluble components, creating a feedback loop between atmospheric chemistry and surface processes (cross-link to Atmosphere and the Methane Cycle and Lakes and Seas).

Prebiotic pathways

Laboratory experiments simulating Titan conditions produce amino acid precursors and other building blocks after hydrolysis, indicating that Titan’s chemistry can create prebiotic organics even if biology is absent. The big questions are whether these organics assemble into more complex structures in situ, and how aqueous processing (e.g., in impact melts or transient liquid water environments) might modify them. Impact craters that melt ice and mix with organics—such as those near Dragonfly’s planned exploration zone—are compelling targets for answering these questions (see Dragonfly).

Magnetosphere and Plasma Interaction

Titan lacks a strong intrinsic magnetic field. Instead, it orbits within Saturn’s magnetosphere, alternately plunging through varying plasma environments and occasionally sampling the shocked solar wind near the magnetopause. This interaction shapes Titan’s ionosphere and upper atmosphere:

- Ionospheric chemistry driven by magnetospheric electrons and solar UV produces complex positive and negative ions.

- Mass loading and pickup processes remove atmospheric neutrals that become ionized and entrained in Saturn’s magnetospheric plasma.

- Induced magnetotail forms as plasma drapes magnetic field lines around Titan’s conducting ionosphere.

The balance between atmospheric escape and resupply influences long-term evolution. While nitrogen loss rates are modest on geologic timescales, they are measurable and informative about ionospheric chemistry. Plasma interactions also drive auroral emissions in ultraviolet, though they are subtle compared to giant-planet auroras.

Missions and Key Discoveries

Two missions have transformed our understanding of Titan:

- Cassini–Huygens (2004–2017): The Cassini orbiter flew by Titan more than 100 times, mapping the surface with radar and near-infrared instruments, sampling the atmosphere, and conducting gravity science; the Huygens probe descended and landed, returning the first images from a surface beyond Earth where liquids flow.

- Huygens Probe (2005): Measured a 1.47 bar surface pressure and ~94 K temperature; imaged dendritic channels and a pebble-strewn plain; detected methane at the surface and in the lower atmosphere; recorded winds and turbulence on descent.

Instrument highlights include:

- SAR radar for surface morphology and altimetry.

- VIMS (Visual and Infrared Mapping Spectrometer) for composition and cloud mapping through atmospheric windows.

- INMS (Ion and Neutral Mass Spectrometer) for upper-atmosphere composition and photochemical products.

- CIRS (Composite Infrared Spectrometer) for thermal structure and trace gases.

- UVIS (Ultraviolet Imaging Spectrograph) for airglow and composition.

- DISR (Descent Imager/Spectral Radiometer) on Huygens for imaging and spectroscopy during descent and on the surface.

From seas and dunes to complex organic chemistry, Cassini–Huygens reshaped Titan from a hazy mystery to a detailed world. The next step is to touch down again—with mobility and a modern analytical lab (see Dragonfly).

Dragonfly: The Rotorcraft Lander

Dragonfly is a NASA rotorcraft lander designed to explore Titan’s surface with unprecedented mobility. Exploiting Titan’s dense air and low gravity, Dragonfly will fly between sites, analyzing materials and measuring environmental parameters across diverse terrains.

Mission concept and timeline

As of the mid-2020s, Dragonfly is slated for a late-2020s launch, targeting arrival in the mid-2030s after interplanetary cruise and Saturn system insertion. Its baseline plan calls for an initial landing in the equatorial Shangri-La dune fields, followed by flights to sites of increasing scientific interest, including materials associated with the impact structure Selk crater. The impact-melted and aqueously processed materials around Selk could record interactions between liquid water and Titan’s organics—prime ground for prebiotic chemistry investigations (see Organic Chemistry and Haze Formation).

Science goals

- Assess the chemical inventory and complexity of organics, searching for pathways that could lead toward prebiotic molecules.

- Measure the physical and chemical properties of sands, sediments, and potential evaporites to reconstruct Titan’s sedimentary processes.

- Probe the geologic history of the landing region, including any evidence for cryovolcanism or tectonics (see Surface, Dunes, and Geology).

- Characterize meteorology, atmospheric boundary layer processes, and the present-day methane cycle (see Atmosphere and the Methane Cycle).

Instruments and operations

Dragonfly’s payload includes a mass spectrometer for organics, a gamma-ray and neutron spectrometer for bulk composition, meteorology and geophysics sensors (including seismic capability), and imaging systems for navigation and science. Flights will be staged in hops, with surface science performed during stops. Titan’s prolonged nights and cold temperatures demand careful power and thermal management, but the dense air reduces aerodynamic power required for flight compared to Earth.

By sampling multiple sites across dune fields and impact-processed terrains, Dragonfly will transition Titan science from reconnaissance to comparative planetology—testing hypotheses about sediment, climate, and chemistry with spatial context.

Observing Titan from Earth

Titan is accessible to backyard observers and a staple for planetary imagers. While you cannot see surface detail visually, tracking Titan’s motion and measuring its apparent size and color offer rewarding challenges.

Visual observing

- Brightness: Apparent magnitude typically ~+8.4, varying with geometry.

- Angular size: ~0.8 arcseconds—resolvable as a tiny disk in large amateur telescopes under steady seeing.

- Color: A subtle, dusky orange hue may be glimpsed at high power in excellent transparency (see also Weather, Clouds, and Seasons for why haze colors Titan).

Use 150–200× magnification (or more under good seeing) to separate Titan’s disk from Saturn’s glare. An occulting bar or carefully placed field stops can improve contrast. Planning software helps predict Titan’s elongations from Saturn and conjunctions with other moons.

Imaging

- Filters: Near-infrared filters centered on methane absorption bands (e.g., ~889 nm) suppress Saturn’s brightness and enhance Titan’s contrast. Broadband RGB captures color but little detail on Titan’s disk.

- Resolution: High-resolution lucky imaging with large apertures can record Titan’s disk and even detect elongations of the major seas in favorable geometries with professional-class instruments. For amateurs, aim to capture the disk cleanly and the color faithfully.

- Context: Combine with images of Saturn’s rings and other moons to tell the seasonal story—e.g., ring tilt and Titan’s orbital positions.

For practical forecasting of seeing and transparency, see strategies akin to those in general sky-condition guides, and remember that Titan’s low surface brightness makes contrast more important than raw resolution. Cross-reference Magnetosphere and Plasma Interaction for an appreciation of the high-energy environment Titan traverses—it won’t change your exposure settings, but it adds depth to your observing narrative.

Data Resources and Tools

Researchers and enthusiasts can explore Titan datasets and tools:

- Global maps: Radar and near-infrared mosaics compiled from Cassini data reveal dunes, lakes, and topography.

- Spectra and profiles: Atmospheric composition from mass spectrometers, infrared spectra of trace gases, and temperature profiles enable photochemical modeling (see Organic Chemistry and Haze Formation).

- Shapefiles and GIS: Geologic maps and vector layers for dunes, lakes, channels, and crater databases support spatial analysis.

- Planning tools: Observation planning software predicts Titan’s position, elongation, and apparent size relative to Saturn for observers (see Observing Titan from Earth).

When using datasets, note the mixed resolutions of radar swaths and the dependence of near-IR imaging on atmospheric windows; combining modalities gives the most complete picture.

FAQs

Is Titan more similar to Earth or to icy moons like Europa?

In terms of surface processes, Titan is uniquely Earth-like: it has an active weather cycle, rivers, lakes, and seas—with methane and ethane replacing water. In terms of interior structure, Titan resembles the large icy moons: an ice shell over a global subsurface ocean atop a rocky core. The result is a hybrid: Earth-like climate behavior operating on a geophysically icy world (see Interior Structure and Subsurface Ocean and Atmosphere and the Methane Cycle).

Can anything live in Titan’s methane lakes?

Conventional water-based life would struggle in Titan’s cryogenic, nonpolar solvents. Speculative exotic biochemistries have been proposed in the literature, but there is no evidence for life in methane lakes. The more plausible habitat for water-based chemistry is the subsurface ocean; however, accessing it is technologically challenging. Dragonfly will focus on prebiotic organic chemistry rather than direct biosignature detection (see Dragonfly).

Why are Titan’s lakes near the poles?

General circulation and seasonal patterns favor net precipitation and cold trapping at high latitudes. Over time, this concentrates liquids in polar basins, while equatorial regions remain arid and dominated by dunes. Basin geology and surface permeability likely reinforce this trend (see Weather, Clouds, and Seasons and Lakes and Seas).

Is there active volcanism on Titan?

There is suggestive evidence for cryovolcanism (eruption of water-rich liquids or slurries), including features like flow-like lobes and caldera-like depressions, but the case is not yet conclusive. Alternative explanations—tectonics, erosion, or sediment deposits—remain viable for many features (see Surface, Dunes, and Geology).

How deep are Titan’s seas?

Depth estimates vary. Ligeia Mare reaches on the order of ~160 m, while portions of Kraken Mare are inferred to be several hundred meters deep. Compositions vary among seas, affecting radar-based depth estimates (see Lakes and Seas).

Advanced FAQs

What controls the orientation of Titan’s linear dunes?

Dune orientations emerge from the vector sum of transport winds. On Titan, seasonal reversal of near-surface winds, modulated by topography and rare storm outflows, leads to a net sand transport direction consistent with the observed longitudinal dunes. The alignment encodes the interplay of equinoctial storms and prevailing winds. Numerical models constrained by Cassini data reproduce the broad pattern (see Surface, Dunes, and Geology and Weather, Clouds, and Seasons).

How do we know Titan has a subsurface ocean?

Cassini measured Titan’s tidal deformation by tracking Doppler shifts and spacecraft motion during flybys. The amplitude of the response is larger than expected for a fully solid body, requiring a decoupling layer—interpreted as a global ocean. Additional evidence comes from moment-of-inertia constraints and possible obliquity/excitation states. Conductive and dielectric models are consistent with a saline ocean (see Interior Structure and Subsurface Ocean).

Does Titan have plate tectonics?

No Earth-style plate tectonics is evident. However, Titan shows tectonic features such as faults, compressional ridges, and possible crustal warping. Ice lithosphere rheology, lower internal heat, and thick volatile-rich layers make plate recycling unlikely. Localized tectonism may still be significant in shaping regional terrains (see Surface, Dunes, and Geology).

What sets methane’s lifetime in Titan’s atmosphere?

Photolysis by solar UV and reactions with radicals remove methane, producing heavier hydrocarbons and haze. Without replenishment, methane would be depleted in tens of millions of years. Resupply options include clathrate release, cryovolcanic outgassing, and subsurface reservoirs. The atmospheric steady state is therefore a balance of photochemical loss and interior/surface sources (see Atmosphere and the Methane Cycle and Organic Chemistry and Haze Formation).

How will Dragonfly navigate and communicate?

Dragonfly will use onboard navigation cameras and sensors to assess terrain, fly short hops between sites, and land autonomously. Communications will relay via direct-to-Earth systems during windows when geometry and power allow. Flight operations are planned to prioritize safety, science return, and energy efficiency in Titan’s long day–night cycles (see Dragonfly).

Conclusion

Titan is a world where Earth-like climate behavior plays out in alien materials and temperatures. Its nitrogen atmosphere, methane cycle, dunes, lakes, and likely interior ocean make it a keystone laboratory for planetary science and prebiotic chemistry. Cassini–Huygens revealed a dynamic, evolving moon rich with processes we can compare across worlds; Dragonfly will deepen that picture by providing ground truth at multiple sites, probing how organics assemble and how geology and climate conspire to shape Titan’s surface.

If Titan fascinates you, explore the datasets mentioned in Data Resources and Tools, practice observing and imaging strategies in Observing Titan from Earth, and keep an eye on mission updates in Dragonfly. The coming decade promises transformative insights from a rotorcraft exploring an orange, hazy world under a dim Sun—a new chapter in comparative planetology.