Table of Contents

- What Is Numerical Aperture in Light Microscopy?

- How Numerical Aperture Controls Resolution and Detail

- Brightness, f-number, and Why NA Beats Magnification

- Depth of Field and Depth of Focus: The Axial Story

- Immersion Media, Refractive Index, and Practical NA Limits

- Illumination NA, Condenser Matching, and Contrast Mechanisms

- Sampling, Pixels, and Nyquist in Digital Microscopy

- Choosing NA: Trade-offs by Specimen and Application

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Final Thoughts on Choosing the Right Numerical Aperture

What Is Numerical Aperture in Light Microscopy?

Numerical aperture (NA) is one of the most important specifications on a microscope objective. It summarizes how much light the objective can collect and how finely it can resolve detail. Formally, NA is defined by

NA = n · sin(θ)

Artist: Happie1Soul

where n is the refractive index of the medium between the front lens and the specimen (air, water, oil, etc.), and θ is half the objective’s angular acceptance cone. Because sin(θ) increases with the lens’s acceptance angle and n reflects how densely light rays can be packed in a medium, NA directly measures the objective’s light-gathering and resolving power.

When you compare objectives, their NA often tells you more about potential image quality than magnification alone. Two objectives at 40× can perform very differently if one has NA 0.65 and the other NA 0.95. The higher NA objective can resolve finer detail, transmit more light to the image, and typically produce shallower depth of field. Those benefits come with trade-offs in working distance and sensitivity to alignment and sample preparation, topics we’ll revisit in Depth of Field and Depth of Focus and Immersion Media.

Common ranges for objective NA include:

- Air objectives: roughly NA 0.04–0.95 (practically limited below 1.0 because n for air ≈ 1.00)

- Water immersion objectives: roughly NA 0.9–1.2

- Oil immersion objectives: roughly NA 1.25–1.45 (because immersion oil has n ≈ 1.515)

Higher NA expands the objective’s angular cone and light acceptance, but the front lens must sit closer to the specimen to capture those high-angle rays. This is why high-NA objectives usually have shorter working distances and often require immersion.

How Numerical Aperture Controls Resolution and Detail

In optical microscopy, lateral resolution—the ability to distinguish two features in the specimen plane—does not improve by increasing magnification alone. Instead, it is governed by diffraction and the system’s NA. A useful way to remember this is that resolution scales with wavelength divided by NA.

Several resolution criteria are used in microscopy, each capturing the same underlying trend:

- Abbe limit (incoherent imaging, sinusoidal test patterns):

d ≈ λ / (2 · NA) - Rayleigh criterion (incoherent imaging, point objects):

d ≈ 0.61 · λ / NA - Coherent imaging (e.g., laser illumination):

d ≈ λ / NA(constant differs because of image formation physics under coherence)

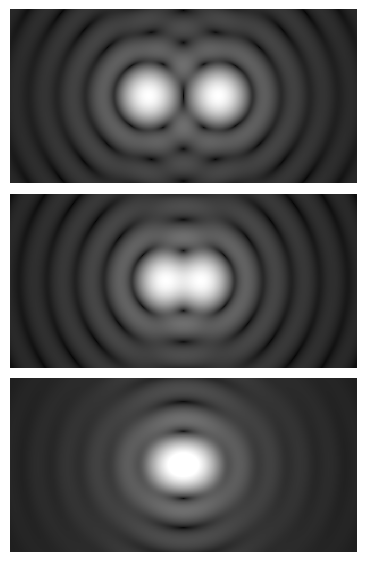

This image uses a nonlinear color scale (specifically, the fourth root) in order to better show the minima and maxima.

Artist: Spencer Bliven

All three emphasize the same message: to resolve finer details (smaller d), you need shorter wavelength light (λ) and higher NA. The precise constant in front of λ/NA depends on the imaging modality and how you define “just resolved,” but the proportionality is robust. This is why choosing an objective with higher NA is the most direct path to improving resolution in widefield microscopy.

Axial resolution (along the optical axis) is more restrictive than lateral resolution and is also NA-limited. For widefield, incoherent imaging, a commonly cited scaling is

Δz ∝ n · λ / NA^2

meaning axial resolution improves (smaller Δz) with higher NA and shorter wavelength, and depends on the refractive index n of the imaging medium. The squared dependence on NA highlights why high-NA objectives are invaluable for optical sectioning in techniques such as confocal microscopy: increasing NA reduces the axial blur more aggressively than the lateral blur. We will connect this NA-squared behavior to depth of field in the next section.

A few additional points about resolution and NA:

- Combined optics matter: The objective is the dominant factor for resolution, but the condenser’s NA influences the achievable resolution and contrast in brightfield, as detailed in Illumination NA and Condenser Matching.

- Wavelength choice is constrained: Shorter wavelengths improve resolution but may be unsuitable for some specimens or contrast methods. For fluorescence, excitation and emission bands are fixed by the fluorophore’s properties.

- Empty magnification: Once the resolution set by NA is reached, increasing magnification enlarges the image without revealing additional detail. We return to this in Brightness and NA vs Magnification.

Brightness, f-number, and Why NA Beats Magnification

Image brightness in a microscope is intertwined with both NA and magnification. A practical relationship connects NA to the optical concept of f-number:

f/# ≈ M / (2 · NA)

where M is the objective’s lateral magnification. Under comparable illumination conditions, image irradiance at the intermediate image plane scales roughly as the square of the inverse f-number, so brightness grows with (NA / M)^2. This is why, everything else being equal, a 40×/0.95 objective produces a brighter image than a 40×/0.65 objective, and why increasing magnification without increasing NA tends to dim the image.

In epi-fluorescence, NA plays a double role—delivering excitation light and collecting emission—which amplifies the NA advantage. The excitation irradiance at the focus increases with NA because a higher-NA objective concentrates light into a smaller spot. The emission collection efficiency also increases with NA because the objective captures more of the isotropically emitted fluorescence photons. While exact exponents depend on system specifics, it is common to see the fluorescence signal scale strongly with NA, with both excitation and collection favoring high NA. The net effect: within the same magnification class, higher NA often yields dramatically better signal-to-noise ratio in fluorescence imaging.

What about magnification? Magnification determines how large the resolved details appear on the detector or to the eye, but it does not create resolution. This leads to two important practical consequences:

- Avoid empty magnification: Enlarging a diffraction-limited image without increasing NA does not reveal new detail; it only spreads the same information over more pixels or a larger field in the eyepiece.

- Match magnification to pixel size: In digital imaging, magnification should be chosen so that the pixel sampling meets the Nyquist criterion for the resolution set by NA and wavelength. We cover this in Sampling and Nyquist.

Finally, because brightness depends on both NA and magnification, two objectives with the same NA but different magnifications can appear differently bright at the sensor. High magnification with the same NA reduces image irradiance because (NA/M)^2 decreases as M increases. This is one reason that, for a given sensor pixel size, many workflows prefer the lowest magnification that still satisfies sampling and field-of-view requirements while leveraging a high NA to maintain brightness and resolution.

Depth of Field and Depth of Focus: The Axial Story

Depth of field (DOF) in microscopy describes the specimen thickness that appears acceptably sharp in the image. Depth of focus describes the permissible range of image-plane displacement (on the camera or eyepiece side) for which the image remains acceptably sharp. Both are influenced by NA, wavelength, magnification, and the refractive indices in object and image space.

In simplified form for incoherent imaging:

- Depth of field in object space scales as

∝ n · λ / NA^2. - Depth of focus in image space scales as

∝ λ · M^2 / NA^2(assuming comparable image-space refractive index and ignoring aberration terms).

The key trend is the NA^2 dependence: increasing NA collapses the axial extent that appears in focus much more rapidly than it shrinks the lateral diffraction spot. This is why high-NA images exhibit strikingly thin focal planes. It is also why high-NA imaging of thick specimens often reveals out-of-focus blur unless optical sectioning or computational deconvolution is used.

Several practical implications follow:

- High-NA, shallow DOF: When imaging dense or three-dimensional specimens, a high-NA objective demands careful focus and may benefit from techniques that reject out-of-focus light (e.g., confocal, structured illumination, or deconvolution). These techniques are beyond the scope of this fundamentals article, but the takeaway is that the narrow DOF is a direct consequence of high NA.

- Low-NA, generous DOF: Objectives with lower NA provide more axial tolerance and show more of a thick specimen in apparent focus, at the expense of resolving fine details.

- Image-side tolerance: High magnification increases depth of focus at the camera because defocus blur is magnified less in the image plane. This trend is captured by the

M^2factor above. It relates to mechanical tolerances and is distinct from the object-side DOF that governs how much of the specimen thickness looks sharp.

Depth metrics include both diffraction and detector/pixel considerations. For example, when pixels are large relative to the diffraction spot, the image can appear less sensitive to small defocus because the blur is undersampled. Conversely, when pixels are small and sampling is fine (see Nyquist), even slight defocus will be visible because the camera resolves the blur distribution. These interactions underscore the value of treating NA, magnification, and sampling as a coordinated set of choices rather than isolated parameters.

Immersion Media, Refractive Index, and Practical NA Limits

Artist: Thebiologyprimer

Because NA includes the refractive index n, using an immersion medium with higher n allows higher NA. This is the primary reason immersion objectives exist. Here are the main families of immersion media and their typical roles:

- Air (n ≈ 1.00): Convenient and versatile. Air objectives top out near NA ≈ 0.95. They offer longer working distances and are commonly used for lower and medium NAs.

- Water (n ≈ 1.33): A good refractive index match for many aqueous specimens and mounting media. Water-immersion objectives reduce spherical aberration when imaging into water-based samples and can achieve NA beyond 1.0, commonly up to around 1.2.

- Oil (typical n ≈ 1.515): High index raises maximum NA to around 1.4–1.45. Oil-immersion objectives are excellent for high-resolution imaging near the coverslip, with the caveat that refractive index mismatch in deeper regions of aqueous samples can introduce aberrations.

- Glycerol and specialized media: Intermediate refractive index options are available to better match cleared or thick samples and to balance spherical aberration over depth.

Refractive index mismatch is a major source of image degradation. When rays pass between materials of different indices, angles bend and high-angle rays can suffer phase delays that cause spherical aberration. This effect grows with imaging depth and with higher NA, and it blurs the point spread function (PSF), reducing contrast and resolution. Choosing an immersion medium that better matches the specimen region you care about can mitigate these aberrations.

Cover glass thickness also matters. Many high-NA objectives are corrected for a specific coverslip thickness, commonly around 0.17 mm. If the actual coverslip deviates significantly, spherical aberration can appear. Some objectives include a correction collar to compensate for small deviations in thickness or refractive index. Because the correction depends on the objective’s design, the goal is not to “tune” NA itself (NA remains set by n · sin(θ)) but to maintain the objective’s designed aberration correction at that NA.

High NA further entails practical trade-offs:

- Working distance: As NA increases, the front lens must collect higher-angle rays, which usually shortens working distance. This can constrain specimen geometry.

- Field flatness and aberrations: High-NA optics are more sensitive to tilt, coverslip quality, and refractive index variations. Small misalignments or inhomogeneities can reduce image quality, even if the NA value itself is high.

- Illumination constraints: Some contrast methods (e.g., darkfield at very high NA) impose geometric constraints that restrict the effective NA used for illumination. We discuss these constraints in Illumination NA and Contrast.

Despite these challenges, immersion objectives are the workhorses of high-resolution microscopy. When chosen to match the specimen and imaging depth, they deliver the higher NA that most effectively pushes resolution, brightness, and photon collection efficiency.

Illumination NA, Condenser Matching, and Contrast Mechanisms

Objective NA governs how finely details can be imaged, but the illumination side also matters, especially in brightfield transmitted light. The condenser’s numerical aperture sets the angular spread of illumination at the specimen, which affects resolution, contrast, and the system’s optical transfer function (OTF).

In Köhler brightfield, partially coherent illumination approaches incoherent conditions as condenser NA increases relative to the objective NA. A practical rule of thumb is to set the condenser aperture so that its NA is close to the objective’s NA for maximum resolution. Reducing condenser NA increases contrast (by narrowing the angular spread and suppressing some high spatial frequencies) but sacrifices resolution. This everyday trade-off reflects how both objective NA and illumination coherence impact the image.

Different contrast methods set additional constraints:

- Darkfield: The condenser must illuminate the specimen with oblique rays that do not directly enter the objective. The objective then collects only scattered light. For high-NA objectives, the darkfield annulus must deliver angles beyond the objective’s acceptance without overlap. As NA increases, the geometry gets tighter, making high-NA darkfield illumination more challenging.

- Phase contrast: Phase contrast objectives and condensers use phase rings and annuli to convert phase shifts into intensity variations. The method relies on matched phase annuli and objective optics; while NA still governs resolution and DOF, the contrast behavior is set by the phase ring geometry and illumination annulus.

- Differential interference contrast (DIC): DIC combines beam shear and polarization optics to emphasize gradients in optical path length. Objective NA determines the finest spatial gradients that can be resolved, but the apparent contrast also depends on shear and prism settings.

- Epi-illumination (reflected light and fluorescence): The objective serves as both condenser and imaging lens. NA therefore controls both the excitation distribution in the specimen and the emission collection efficiency. As noted in Brightness and NA, fluorescence benefits strongly from higher NA.

Two further notes about illumination and NA:

- Numerical aperture of illumination vs. collection: In brightfield, the highest resolvable spatial frequencies depend on the combination of illumination and collection NAs. Maximizing resolution typically requires a condenser NA approaching the objective NA. In fluorescence, illumination and collection share the same objective NA, so the system is already optimized by choosing a high-NA objective.

- Contrast vs. resolution: Closing diaphragms (reducing illumination NA) increases contrast at the cost of resolution and brightness. Opening them does the reverse. For fine detail, especially near the resolution limit described in How NA Controls Resolution, adequate illumination NA is essential.

Sampling, Pixels, and Nyquist in Digital Microscopy

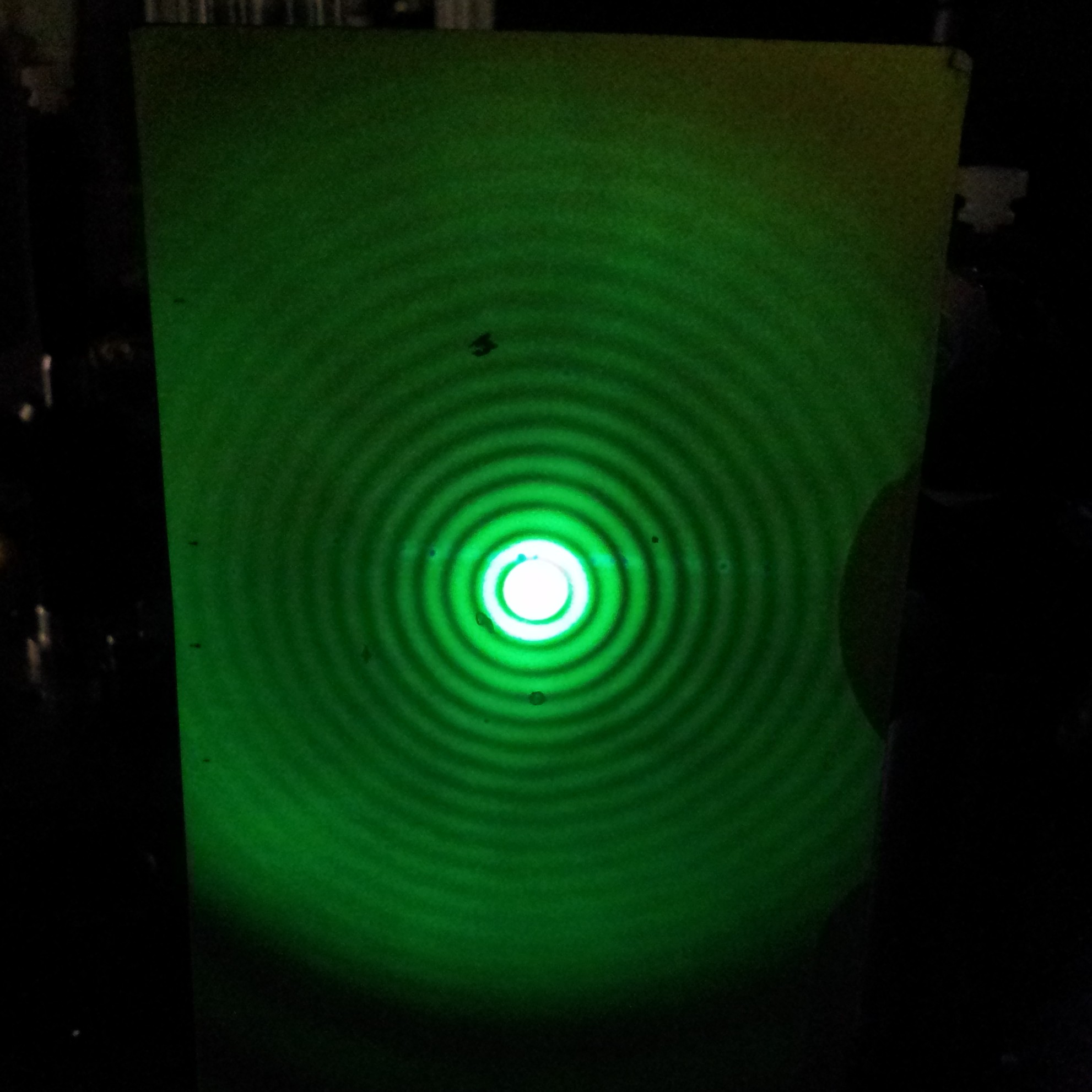

When imaging with a digital sensor, the microscope’s optical resolution is only fully realized if the camera samples the image finely enough. The Nyquist-Shannon sampling theorem provides the guideline: to accurately represent the highest spatial frequencies in the image, the sampling frequency must be at least twice the highest frequency present. Translating that to microscopy, the effective pixel size projected into the object plane should be small enough to sample the diffraction-limited spot with at least two pixels across the smallest resolvable feature along each dimension.

Artist: Anaqreon

A practical way to relate camera pixels to the specimen is through the effective object-side pixel size:

p_object = p_camera / M_total

where p_camera is the physical pixel pitch of the sensor and M_total is the total magnification from specimen plane to sensor. For Nyquist-compliant sampling in widefield, incoherent imaging, many practitioners aim for an object-side pixel size roughly two to three times smaller than the expected resolution limit given by the NA and wavelength (e.g., based on ≈ 0.61 · λ / NA). This provides at least two samples across the smallest features and some margin for modulation transfer across the passband.

Why more than exactly 2×? Because real optical transfer functions roll off near the cutoff frequency, and sampling exactly at 2× can be sensitive to small shifts in focus, wavelength, or alignment. Slightly finer sampling (2–3×) provides robustness without unduly inflating data volume. Oversampling beyond that adds file size without adding resolvable detail, while undersampling risks aliasing: high-frequency detail folds back into lower frequencies and appears as spurious patterns or loss of contrast.

Two additional considerations frequently arise:

- Color vs. monochrome sensors: Sensors with color filter arrays (e.g., Bayer patterns) have an effective sampling density that depends on the color channel. For the sharpest detail, a monochrome sensor with appropriate illumination and filters transmits all pixels to luminance sampling, whereas a color sensor allocates pixels to separate color channels.

- Field of view vs. sampling: Increasing magnification reduces field of view at the camera. To maintain Nyquist sampling with a given pixel size, you may choose the lowest magnification that still samples at ≥2× the optical resolution. This trades field of view against sampling adequacy and is best planned alongside the NA choice discussed in Choosing NA.

In summary, the image you record is the product of optical resolution set by NA and wavelength, and sampling resolution set by magnification and pixel size. Harmony between these domains prevents both empty magnification and undersampling artifacts.

Choosing NA: Trade-offs by Specimen and Application

Selecting numerical aperture is a balancing act among resolution, brightness, depth of field, working distance, and specimen compatibility. The “best” NA depends on what you need to see and the constraints of the sample and imaging modality. The scenarios below show typical trade-offs and link back to earlier sections:

Thin, high-contrast specimens near the coverslip

Artist: Ed Uthman from Houston, TX, USA

For thin sections or samples with strong intrinsic contrast (e.g., stained slides) positioned immediately under a standard coverslip, a high-NA objective often delivers the most detailed images. Benefits include:

- Improved lateral resolution per λ/NA scaling

- Increased brightness relative to magnification per (NA/M)^2

- Thin depth of field that isolates the specimen plane per DOF ∝ 1/NA^2

Trade-offs include reduced working distance and increased sensitivity to coverslip thickness and refractive index variations, which are discussed in Immersion Media and Correction.

Live cells in aqueous media and moderate depth

For live, aqueous samples where imaging extends a few tens of micrometers into the specimen, water-immersion objectives balance refractive index matching and reasonably high NA. The idea is to reduce spherical aberration over depth without giving up too much resolution. Related principles:

- Axial resolution and DOF still scale per NA^2, so expect shallower DOF at higher NA.

- Matching the immersion medium to the sample minimizes index mismatch per refractive index considerations.

Thick tissues or cleared samples

In optically thick or refractive-index–matched specimens (e.g., cleared tissue), specialized immersion media (glycerol, clearing-compatible oils) can improve image quality at depth by reducing index mismatch. Choosing NA balances depth performance and resolution:

- Moderate NA may be preferable if high NA exacerbates aberrations at depth.

- When clearing matches index well, higher NA can be used effectively within the working distance limits.

Reflective surfaces and materials inspection

For reflected-light imaging of surfaces, high NA increases both lateral resolution and sensitivity to micro-topography. Practical constraints include working distance and field flatness over the region of interest. Because epi-illumination uses the objective for both illumination and collection, the brightness benefit of NA discussed in Brightness and NA directly applies.

Phase and DIC imaging of weakly absorbing specimens

Phase contrast and DIC convert phase variations into intensity differences, improving visibility of transparent samples. NA still governs the finest detail, but illumination geometry and specialized optics control the contrast formation. Increasing NA will sharpen gradients and reveal finer features, provided the associated illumination annuli or prisms are appropriately matched, as noted in Illumination NA and Contrast.

Low-light fluorescence

In fluorescence, high NA improves both excitation confinement and emission collection efficiency. This dual benefit makes NA one of the most impactful choices for faint signals. Additional considerations include:

- Depth of field becomes very shallow at high NA, which can be advantageous for thin samples or problematic in thick samples without sectioning.

- Sampling should be set to meet or exceed Nyquist for the emission wavelength and NA per Sampling and Nyquist.

Field of view vs. resolution needs

When screening large areas, a lower magnification objective with moderate NA may be preferred to maximize field of view while still resolving features of interest. If some regions require higher resolution, switching to a higher-NA objective for targeted imaging combines efficiency with detail. This workflow relies on understanding NA-driven resolution limits and pixel sampling trade-offs outlined in Resolution and Nyquist.

Frequently Asked Questions

Is higher numerical aperture always better?

Higher NA improves lateral and axial resolution and increases light collection, which are strong advantages. However, higher NA also reduces working distance and depth of field, and it increases sensitivity to refractive index mismatches and coverslip thickness deviations. These trade-offs can reduce image quality in thick or inhomogeneous specimens, especially away from the coverslip or when immersion and specimen media are mismatched. The best NA is therefore context-dependent: choose the highest NA that aligns with your specimen geometry, imaging depth, and contrast method. See Immersion Media and Depth of Field for the key factors.

How does cover glass thickness affect NA and resolution?

NA itself, defined by n · sin(θ), does not change with cover glass thickness. What changes is the presence of spherical aberration if the objective’s design assumes a particular coverslip thickness and refractive index. A mismatched coverslip introduces phase errors in high-angle rays, effectively blurring the point spread function and reducing contrast and apparent resolution. Some objectives include correction collars to compensate for small deviations. For high-NA imaging near the coverslip, using glass close to the objective’s specified thickness and refractive properties helps realize the resolution predicted by NA. Related background appears in Immersion Media and Practical NA Limits.

Final Thoughts on Choosing the Right Numerical Aperture

Artist: Ernst Leitz (Firm)

Numerical aperture is the central parameter that ties together resolution, brightness, and depth of field in optical microscopy. It encodes the acceptance angle of the objective through NA = n · sin(θ), and it sets the scale for both lateral resolution (proportional to λ/NA) and axial resolution and depth of field (proportional to λ/NA^2). High NA brings dramatic gains in detail and photon efficiency, especially in fluorescence, but it also narrows the usable focus range and tightens tolerances on sample preparation and refractive index matching.

Making informed choices means balancing NA with magnification, illumination NA, immersion media, and pixel sampling. If your goal is to reveal fine structure in thin samples, a high-NA immersion objective paired with adequate sampling often provides the clearest path forward. For thick or index-mismatched specimens, consider moderate NA and media that reduce aberration, recognizing that the optimal configuration is the one that delivers the most useful information about your sample.

If you found this deep dive into numerical aperture helpful, consider exploring related topics in our microscopy fundamentals series, and subscribe to our newsletter for future articles on contrast mechanisms, sampling strategies, and practical imaging trade-offs.