Table of Contents

- What Is Numerical Aperture (NA) in Optical Microscopy?

- Resolution, Diffraction, and the Abbe and Rayleigh Criteria

- Illumination, Coherence, and the Role of the Condenser NA

- Contrast, Signal-to-Noise, and How They Interact with Resolution

- Depth of Field, Depth of Focus, and Working Distance

- Immersion Media, Refractive Index Mismatch, and Coverslips

- Camera Pixel Size, Sampling Theory, and Nyquist in Microscopy

- Selecting Objectives: NA, Magnification, Field Number, and Trade-Offs

- Common Misconceptions About Magnification and Resolution

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Final Thoughts on Optimizing Resolution and NA

What Is Numerical Aperture (NA) in Optical Microscopy?

Numerical aperture (NA) is the central quantity that governs how much detail a microscope objective can capture and how much light it can collect. It is defined by the geometry of the objective lens and the refractive index of the medium between the specimen and the objective front lens. The standard definition is:

NA = n · sin(θ)

where n is the refractive index of the immersion medium (air, water, glycerol, or oil), and θ is half the angular aperture—the half-angle of the maximum cone of light that can enter or exit the objective. A larger NA means the objective can accept light over a wider range of angles, capturing finer spatial frequencies from the specimen. In practical terms, higher NA generally yields higher resolution, better light collection from weakly emitting samples, and improved contrast for fine details.

Two straightforward ways to increase NA are:

- Increase the acceptance angle (larger θ) by using objectives with larger front apertures and shorter working distances.

- Increase the refractive index n of the medium between specimen and objective (e.g., using oil immersion instead of air). See Immersion Media, Refractive Index Mismatch, and Coverslips.

It is common to see NA printed on objective barrels (e.g., 10×/0.25, 40×/0.65, 60×/1.40 oil). While magnification (10×, 40×, 60×) tells you how large the image appears, NA is the quantity that limits how much new detail you can resolve. This distinction underpins nearly every other concept in this article, from diffraction-limited resolution to sampling with a camera. If you remember only one thing, let it be this: for resolving fine detail, NA matters more than magnification. You can read more about this trade-off in Selecting Objectives: NA, Magnification, Field Number, and Trade-Offs.

Artist: PaulT (Gunther Tschuch)

The condenser also has an NA, which governs how tightly the specimen is illuminated (in transmitted-light modalities such as brightfield, darkfield, or phase contrast). The interplay between objective NA and condenser NA determines the effective resolution for some contrast modes. We will revisit this in Illumination, Coherence, and the Role of the Condenser NA.

Resolution, Diffraction, and the Abbe and Rayleigh Criteria

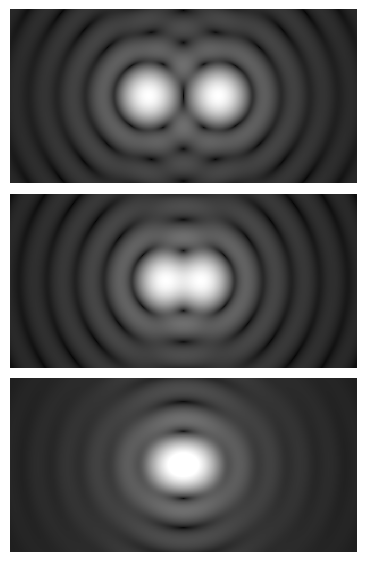

Even a perfectly polished lens cannot form a perfect point image because light diffracts as it passes through a finite aperture. A point source becomes an Airy pattern—a bright central disk surrounded by rings—rather than a single point. The size of that central disk defines a fundamental limit to the detail that can be recorded: the diffraction limit. This limit is not primarily set by magnification; it is governed by the combination of wavelength and NA.

Artist: Anaqreon

Two widely used ways to express the diffraction limit are the Rayleigh criterion and the Abbe limit. They are closely related but apply to slightly different cases.

Rayleigh criterion for two point-like emitters

When considering two closely spaced point sources (for example, fluorescing molecules imaged in widefield mode), the Rayleigh criterion states that two points are just resolvable when the center of one Airy disk falls on the first minimum of the other. The separation corresponding to this condition is approximately:

d_R ≈ 0.61 · λ / NA

This image uses a nonlinear color scale (specifically, the fourth root) in order to better show the minima and maxima.

Artist: Spencer Bliven

Here, λ is the wavelength of the detected light (for fluorescence, the emission wavelength). The numerical factor 0.61 comes from the properties of the Airy pattern. The key insight is simple: shorter wavelengths and larger NA improve resolution. Notice that the objective NA is the dominant factor for fluorescence imaging, where the illumination is typically spatially incoherent with respect to emission.

Abbe limit for periodic structures

Ernst Abbe derived a closely related expression by considering periodic line patterns and how their spatial frequencies are transmitted through the objective and condenser. For transmitted, partially coherent brightfield illumination, Abbe’s result can be expressed as:

d_A ≈ λ / (NA_obj + NA_cond)

where NA_obj is the objective numerical aperture and NA_cond is the condenser numerical aperture. This expression emphasizes that, for certain modalities and specimens (especially periodic structures under transmitted light), the condenser NA contributes to the system’s ability to transmit higher spatial frequencies. A higher condenser NA—properly aligned—can therefore improve the smallest resolvable period in brightfield imaging. For fluorescence imaging, by contrast, the condenser NA does not play a role in the detection pathway; resolution is dominated by the objective NA as in the Rayleigh expression.

Because the Rayleigh and Abbe criteria arise from different models and specimen types (point-like vs. periodic), you will see slightly different numerical prefactors in various references. The precise constant is less important than the dependencies: resolution scales with wavelength and NA in a way that rewards shorter wavelengths and larger numerical apertures.

Lateral vs. axial resolution

In three-dimensional imaging, there is also an axial (z) resolution to consider. For widefield microscopy, the axial dimension of the point spread function is broader than the lateral dimension and depends strongly on NA and refractive index. A commonly cited scaling is that axial resolution varies approximately as:

d_z ∝ (n · λ) / NA^2

where n is the refractive index of the immersion medium. The exact numerical constant depends on imaging modality and how resolution is defined (e.g., full width at half maximum vs. Rayleigh-like criteria), but the NA-squared dependence is robust: increasing NA provides a disproportionately large improvement in axial resolution compared with lateral resolution. This is one reason high-NA objectives are favored for three-dimensional fluorescence microscopy.

For completeness, note that specialized techniques (e.g., confocal microscopy, structured illumination, or other super-resolution methods) can improve effective resolution beyond the widefield diffraction limit by manipulating the illumination or detection strategy. Those methods rely on additional physical constraints and are beyond the scope of this fundamentals article, which focuses on diffraction-limited, linear imaging conditions.

Illumination, Coherence, and the Role of the Condenser NA

Illumination is not just about brightness; its geometry and coherence properties influence contrast and resolution, especially in transmitted-light modalities. The condenser lens is the counterpart to the objective on the illumination side of the specimen. Its numerical aperture determines the angular spread with which the specimen is illuminated.

Condenser NA and brightfield resolution

In brightfield imaging of periodic structures, Abbe’s expression, d_A ≈ λ / (NA_obj + NA_cond), highlights that the condenser NA contributes to the system’s ability to transmit high spatial frequencies. Practically, this means that if the condenser’s aperture diaphragm is stopped down excessively, high-angle diffracted orders may be cut off, reducing resolution and producing a higher-contrast but less detailed image. Conversely, opening the condenser aperture to match the objective NA increases the illumination cone and can transmit more spatial frequency content, at the cost of reduced apparent contrast for low-frequency features due to increased background light.

A good rule of thumb for brightfield is to set the condenser aperture diaphragm so that the condenser NA is a substantial fraction of the objective NA, often on the order of 70–100% of the objective NA, depending on the specific contrast needed. This balancing act is an example of the contrast–resolution trade-off discussed in Contrast, Signal-to-Noise, and How They Interact with Resolution.

Coherence and modality dependence

The role of the condenser NA depends on the coherence of illumination and the imaging modality:

- Fluorescence microscopy (incoherent detection): The emission light is effectively incoherent with respect to the illumination. Resolution is governed primarily by the objective NA and the emission wavelength. Adjusting the condenser NA has little to no effect on resolution in the detection path.

- Brightfield and phase contrast (partially coherent transmission): The condenser NA directly shapes the angular spectrum of illumination. Matching the condenser to the objective NA allows higher diffracted orders to reach the objective, improving resolution of periodic features.

- Darkfield: The condenser is configured to deliver oblique illumination beyond the objective’s acceptance cone. Only scattered light enters the objective, enhancing contrast for edges and small particles, but with its own resolution and sensitivity trade-offs.

Regardless of modality, the concept of uniform, well-conditioned illumination is essential. Köhler illumination, for instance, provides even field illumination and independent control over field and aperture diaphragms. While the setup details are beyond the scope here, the principle is that proper illumination condition ensures the objective is not starved of spatial frequencies and that the specimen is evenly lit across the field of view. For an overview of how illumination influences image quality beyond raw resolution, see Contrast, Signal-to-Noise, and How They Interact with Resolution.

Contrast, Signal-to-Noise, and How They Interact with Resolution

Resolution tells you the smallest spacing that can be distinguished in principle. In practice, you also need sufficient contrast and adequate signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) to recognize those details above the fluctuations of noise. Two specimens with the same physical spacing may be differently discernible depending on how much contrast they generate and how many photons your system collects and records.

Contrast mechanisms vs. resolution limit

Different contrast mechanisms emphasize different specimen properties:

- Brightfield: contrast arises from absorption, scattering, and refractive index variations. Fine transparent features may be low-contrast unless optimized with the condenser diaphragm.

- Phase contrast and DIC: convert phase gradients into intensity differences, enhancing contrast for transparent specimens without staining.

- Polarization-based methods: reveal anisotropic structures such as crystalline or fibrous samples.

- Fluorescence: contrast is based on specific emission from labeled structures against a dark background, often providing excellent specificity and SNR.

Artist: Ed Uthman from Houston, TX, USA

These contrast mechanisms do not directly change the diffraction limit, but they can make features at or near the limit more (or less) detectable. For example, phase contrast can reveal sub-structure in nearly transparent cells that brightfield might miss under the same resolution limit. See how illumination choices impact resolution in Illumination, Coherence, and the Role of the Condenser NA.

Signal-to-noise: photons, detectors, and exposure

Photon detection is inherently noisy due to the quantum nature of light. If you detect N photons from a feature, the shot noise is roughly √N, and the SNR scales as N / √N = √N. Collecting more photons—by using higher NA (larger collection solid angle), longer exposure time, higher quantum efficiency detectors, or brighter fluorophores—improves SNR. However, there are trade-offs:

- Photobleaching and phototoxicity can limit how much excitation you can apply in fluorescence imaging.

- Motion blur can limit exposure times for dynamic specimens.

- Camera noise (read noise, dark current) and digitization can affect low-signal images.

Detector performance and the effective magnification on the detector influence how well you sample the detail allowed by the optics. A camera with small pixel size mapped appropriately to the specimen can help you meet Nyquist sampling criteria without unnecessary magnification. We examine this in detail in Camera Pixel Size, Sampling Theory, and Nyquist in Microscopy.

Practical takeaway: pushing resolution requires not only high NA and short wavelengths but also sufficient contrast and SNR. If you cannot detect enough photons or if contrast is poor, the theoretical resolution advantage of a high-NA objective may not translate into visibly finer detail.

Depth of Field, Depth of Focus, and Working Distance

Resolution is not the only dimension of image quality. The three-dimensional positioning of the specimen relative to the objective determines how much of the sample appears sharp at once (depth of field), how forgiving the system is to detector positioning (depth of focus), and how close you can physically get the objective to the specimen (working distance). These concepts are connected but distinct.

Depth of field (specimen space)

Depth of field (DOF) refers to the axial range in the specimen over which features appear acceptably sharp in the image. In diffraction-limited imaging, DOF decreases rapidly with increasing NA. A commonly used scaling is that DOF varies approximately as:

DOF ∝ (n · λ) / NA^2

where n is the immersion medium index. Higher NA shrinks DOF, making high-NA objectives more sensitive to focus. This is why high-NA imaging often benefits from fine focus control, stable mounts, and sometimes axial scanning or focus stacking for thick specimens. For camera-based systems, there is an additional geometrical (defocus) contribution to DOF that depends on the detector sampling and permissible blur, but the diffraction term above typically dominates at high NA.

Depth of focus (image space)

Depth of focus is the corresponding tolerance in the image plane: how far the camera (or eyepiece image plane) can move axially while retaining acceptable sharpness. It scales with magnification and NA in a way that generally increases the tolerance in the detection path as magnification increases, but exact expressions depend on system design and detection criteria. While DOF and depth of focus are related by optical conjugation, they should not be conflated. DOF is usually the more intuitive limit for users because it determines how much of a thick sample appears in focus simultaneously.

Working distance (mechanical clearance)

Working distance is the physical distance from the front lens of the objective to the nearest point on the specimen when focused. Higher NA objectives often have shorter working distances because they require larger front apertures and tighter focusing cones. For example, a high-NA oil immersion lens may have a very short working distance compared with a lower NA air objective of the same magnification.

Choosing an objective with appropriate working distance is especially important when imaging thicker specimens, samples under coverslips with mounting media, or samples that must be approached around obstructions. There are also long-working-distance objectives designed with lower NA and special optical designs to maintain clearance, but these come with trade-offs in resolution and light collection. For a deeper discussion of how to choose among these trade-offs, see Selecting Objectives: NA, Magnification, Field Number, and Trade-Offs.

Immersion Media, Refractive Index Mismatch, and Coverslips

Immersion media determine the refractive index n that enters the NA expression and strongly influence aberrations. Common immersion types include air (n ≈ 1.0), water (~1.33), glycerol (~1.47), and immersion oil (around ~1.515 for standard microscope oils). The exact values depend on temperature and formulation, but the principle is consistent: higher-index media allow larger NA because NA = n · sin(θ) is bounded above by n. Thus, oil immersion objectives can achieve NA values above 1.0, whereas air objectives cannot.

Artist: Thebiologyprimer

Index matching and spherical aberration

Beyond boosting NA, immersion choice affects wavefront quality. When light crosses interfaces between materials with different refractive indices (e.g., specimen to coverslip to immersion medium), it refracts according to Snell’s law. If the objective is designed for a specific index chain and thickness (such as a standard coverslip), using a mismatched immersion medium or coverslip thickness can introduce spherical aberration, degrading resolution and contrast, particularly away from the focus and deeper into the sample.

Some objectives include a correction collar that allows fine adjustment to compensate for small deviations in coverslip thickness or refractive index. Proper use of correction collars can markedly improve image sharpness and contrast for thick or index-mismatched samples. For an overall view of how these choices tie back to NA and depth of field, revisit Depth of Field, Depth of Focus, and Working Distance.

When to choose each immersion

- Air: Convenient, no immersion medium required. Typically used for low to medium NA. Avoids liquid handling but limited by lower NA and greater refractive index mismatch at interfaces.

- Water: Useful when imaging aqueous specimens to reduce mismatch between specimen and immersion, mitigating spherical aberration in deeper regions. Water immersion objectives often balance decent NA with improved performance in live or thick aqueous samples.

- Glycerol: Intermediate refractive index can be advantageous for specimens mounted in media near that index, reducing mismatch.

- Oil: Maximizes NA on standard coverslips designed for oil immersion objectives. Provides the highest lateral and axial resolution near the coverslip but can introduce aberrations in thick aqueous samples if used beyond the intended design depth.

There is no single best immersion type; the choice depends on the sample, depth of interest, and desired resolution. The closer the refractive index of the immersion medium is to the intended design and the sample environment, the less spherical aberration and the better the high-NA performance.

Camera Pixel Size, Sampling Theory, and Nyquist in Microscopy

Even if your optics can resolve very fine detail, your detector must sample the image finely enough to record it. This is where sampling theory and the Nyquist criterion enter microscopy. In essence, you should sample at least twice as finely as the smallest feature you aim to resolve; otherwise, aliasing occurs, and fine details can be misrepresented or lost.

From objective to sensor: mapping pixel size

In a camera-based microscope, each pixel on the sensor corresponds to some distance in the specimen plane. The mapping is determined by the system magnification between the specimen and the sensor. The effective pixel size in specimen space is:

pixel_size_specimen = pixel_size_sensor / M_eff

where M_eff is the effective magnification from the specimen to the camera (including objective magnification and any intermediate optics, such as tube lenses or relay lenses). For example, if the camera pixel is 6.5 µm and the effective magnification is 100×, then each pixel corresponds to 65 nm in the specimen plane.

Nyquist sampling for diffraction-limited detail

To adequately sample the finest detail provided by the optics, a practical guideline is to map the pixel size in specimen space to be at most about half the diffraction-limited feature size. For lateral sampling in widefield fluorescence, a commonly used rule is:

pixel_size_specimen ≤ (0.5) · d_R ≈ 0.5 · (0.61 · λ / NA)

Many practitioners aim even finer (e.g., 0.33–0.5 of the diffraction-limited resolution) to improve digital interpolation and deconvolution performance. Sampling too coarsely leaves detail unresolved by the detector; sampling extremely finely (“oversampling”) increases file sizes and may reduce SNR per pixel because photons are spread over more pixels without gaining fundamentally new optical information. There is a practical sweet spot defined by the optics and the detector’s noise characteristics.

SNR and sampling trade-offs

Sampling and SNR interact in meaningful ways:

- At fixed photon flux, dividing light into more pixels reduces the average photons per pixel, potentially decreasing SNR per pixel. This is not a problem if the total signal remains high and the detector has low read noise, but it can be limiting in photon-starved conditions.

- Magnification beyond what is required for Nyquist sampling—sometimes called “empty magnification”—increases the image size without revealing new information and can be detrimental to SNR efficiency.

Matching your camera pixel size and effective magnification to the objective’s NA and the wavelength of interest is a highly impactful optimization. If you are wondering how this plays alongside field of view, see Selecting Objectives: NA, Magnification, Field Number, and Trade-Offs for a discussion of field number and sensor size.

Selecting Objectives: NA, Magnification, Field Number, and Trade-Offs

Selecting an objective is all about balancing competing factors: resolution, field of view, working distance, immersion needs, and sampling at the detector. Understanding how NA and magnification interplay helps you make informed choices.

Artist: Ernst Leitz (Firm)

NA vs. magnification

Magnification tells you how large the image appears; NA determines how much detail is fundamentally present. It is possible for a lower magnification objective with high NA to resolve finer detail than a higher magnification objective with lower NA. For instance, a 40×/0.95 objective can resolve more detail than a 60×/0.80, despite the lower nominal magnification. The optimal pairing with your camera depends on pixel size and desired field of view, as discussed in Camera Pixel Size, Sampling Theory, and Nyquist in Microscopy.

Field number and field of view

In visual observation through eyepieces, the field number (FN) defines the diameter of the intermediate image that the eyepiece can present without vignetting. The approximate diameter of the field of view at the specimen is:

FOV_diameter_specimen ≈ FN / objective_magnification

For camera-based systems, the field of view is set by the sensor size divided by the effective magnification onto the sensor. If you need to image larger regions, you may choose a lower magnification objective or tile multiple images. Be mindful that lowering magnification can also reduce NA if you switch objectives, potentially sacrificing resolution.

Working distance and sample clearance

High-NA objectives tend to have shorter working distances. If your sample is thick, uneven, or requires a coverslip/mounting arrangement that increases the distance to the focal plane, you may need an objective with longer working distance. Long-working-distance objectives often achieve their clearance by limiting NA, so there is an inherent trade-off between access and resolution. This trade-off is examined from a depth-of-field perspective in Depth of Field, Depth of Focus, and Working Distance.

Immersion considerations

Choose immersion type based on both desired NA and refractive index matching to the specimen environment. Oil immersion typically provides the highest NA near the coverslip and thus the best lateral and axial resolution for thin specimens mounted under standard coverslips. For thick, aqueous samples or imaging deeper into tissue-like media, water immersion objectives can provide better effective resolution because they reduce spherical aberration, even if their nominal NA is slightly lower. For the physics behind this choice, revisit Immersion Media, Refractive Index Mismatch, and Coverslips.

Objective correction level and coverslip thickness

Objectives are designed for specific coverslip thicknesses and correction levels. Using a coverslip of the wrong thickness or imaging without a coverslip when one is expected can degrade resolution and contrast due to spherical and chromatic aberrations. Objectives with correction collars allow adjustment to compensate for coverslip variations, which is especially useful in high-NA imaging. Even small departures from the intended optical path can become significant at high NA.

Common Misconceptions About Magnification and Resolution

Many persistent myths in microscopy stem from conflating magnification with resolution or misunderstanding the role of illumination. Clearing these up helps you make better decisions and interpret images correctly.

- “More magnification means more detail.” Not necessarily. After you reach the diffraction-limited detail set by NA and wavelength, further magnification simply spreads the same information over more pixels or a larger view without revealing new structure. This is called empty magnification. See Camera Pixel Size, Sampling Theory, and Nyquist in Microscopy.

- “Digital zoom equals optical magnification.” Digital zoom resamples the same image data and cannot add new optical information. Optical magnification changes the mapping between object and detector before sampling.

- “The condenser only controls brightness.” In transmitted-light modalities, the condenser NA influences the transmission of spatial frequencies and image coherence, affecting resolution and contrast. See Illumination, Coherence, and the Role of the Condenser NA.

- “Higher NA always yields better images.” Higher NA improves resolution and light collection, but it also reduces depth of field and working distance and may increase sensitivity to aberrations and alignment. The best NA is the one matched to your specimen and imaging goals.

- “Shorter wavelengths are always better.” While shorter wavelengths improve diffraction-limited resolution, detector sensitivity, specimen absorption, and optical coatings vary with wavelength. Practical performance depends on the entire system, not wavelength alone.

Frequently Asked Questions

Is 100× always better than 40× for resolving detail?

No. Resolution depends on NA and wavelength, not magnification alone. A 40× objective with higher NA can resolve finer detail than a 100× objective with lower NA. For example, if the 40× has NA = 0.95 and the 100× has NA = 0.80, the 40× objective has a smaller diffraction-limited spot size and thus higher resolution. Magnification should be chosen to match the detector sampling so that you meet Nyquist criteria without resorting to empty magnification. See Camera Pixel Size, Sampling Theory, and Nyquist in Microscopy for guidance on mapping pixel size to diffraction limits.

When should I use oil vs. water immersion for high-resolution imaging?

Use oil immersion when imaging near a standard coverslip with specimens prepared for high-NA, thin-section imaging. Oil immersion objectives can achieve the highest NA (often above 1.0), giving excellent lateral and axial resolution close to the coverslip. Use water immersion when imaging deeper into aqueous specimens or when reducing refractive index mismatch is more important than absolute NA at the coverslip. Water immersion can mitigate spherical aberration in thick, water-rich samples, improving effective resolution and contrast in practice. The choice depends on depth, sample environment, and objective design. For more, see Immersion Media, Refractive Index Mismatch, and Coverslips.

Final Thoughts on Optimizing Resolution and NA

Microscopy at its core is about translating the physics of light into meaningful images. Numerical aperture is the thread that binds that translation: it sets the diffraction limit with wavelength, governs light collection efficiency, shapes depth of field, and interacts with illumination to define what spatial frequencies reach the detector. To get the most from your system:

- Prioritize NA when seeking higher resolution, and remember how it combines with wavelength in the Rayleigh and Abbe limits. See Resolution, Diffraction, and the Abbe and Rayleigh Criteria.

- Condition your illumination to support the detail you need, matching condenser NA to objective NA in brightfield when appropriate. See Illumination, Coherence, and the Role of the Condenser NA.

- Balance contrast and SNR with exposure and detector choice so that near-limit detail is actually visible above noise. See Contrast, Signal-to-Noise, and How They Interact with Resolution.

- Match sampling to the optics: choose magnification and camera pixel size to meet Nyquist without empty magnification. See Camera Pixel Size, Sampling Theory, and Nyquist in Microscopy.

- Select objectives with the right combination of NA, immersion, working distance, and field coverage for your specimen and experiment. See Selecting Objectives: NA, Magnification, Field Number, and Trade-Offs.

With a clear understanding of NA, diffraction, illumination, and sampling, you can diagnose image issues, make informed equipment choices, and design imaging conditions that reveal the structures you care about—accurately and efficiently. If you found this deep dive helpful, consider subscribing to our newsletter to receive future articles on microscope fundamentals, types, accessories, and applications.