Table of Contents

n

- n

- What Do Astronomers Mean by Dark Matter and Dark Energy?

- Observational Evidence for Dark Matter in the Universe

- How We Discovered Cosmic Acceleration and Dark Energy

- How Cosmologists Measure Invisible Components: Methods and Datasets

- Theoretical Models: ΛCDM, Alternatives, and Open Problems

- From the Big Bang to Galaxies: How Dark Components Shape Structure

- Practical Implications for Amateur Observers and Science Enthusiasts

- Current and Upcoming Missions Probing the Dark Universe

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Final Thoughts on Understanding Dark Matter and Dark Energy

n

n

n

n

n

n

n

n

n

n

nn

What Do Astronomers Mean by Dark Matter and Dark Energy?

n

When cosmologists talk about the nulldark Universe,null they are referring to two distinct phenomena that dominate the cosmic energy budget but have not yet been directly detected in the lab: dark matter and dark energy. Despite sharing the adjective nulldarknullnullmeaning they do not emit or absorb light in familiar waysnullthey are not the same thing and play very different roles in the cosmos.

n

Dark matter behaves like an invisible mass: it clumps under gravity, forms halos around galaxies and clusters, and anchors the cosmic web. It is collisionless (or nearly so) and interacts primarily via gravity, with any non-gravitational interactions constrained to be very weak. It explains why the outer parts of galaxies rotate faster than expected from visible matter alone and why galaxy clusters are more massive than their luminous contents suggest.

n

Dark energy acts like an anti-gravity pressure on the largest scales: it accelerates the expansion of the Universe. In the simplest model, dark energy is the cosmological constant (Λ), a constant energy density associated with empty space. More general models allow this energy to vary slowly over time (often called nullquintessencenull) or arise from modifications to gravity at cosmological scales.

n

In standard cosmology, the current best-fit picture (nullΛCDM,null for nullLambda Cold Dark Matternull) includes:

n

- n

- Baryonic matter (ordinary atoms)

- Cold dark matter (CDM)

- Dark energy (Λ, often modeled as a cosmological constant)

- Radiation (photons and relic neutrinos, negligible today but important early on)

n

n

n

n

n

These components together determine the geometry and expansion history of the cosmos. Their contributions are commonly expressed as density fractions of the critical density, denoted by Ω (Omega). A simplified form of the expansion equation is:

n

H(z)^2 = H0^2 [Ω_m (1+z)^3 + Ω_r (1+z)^4 + Ω_Λ + Ω_k (1+z)^2]nn

Here, H(z) is the Hubble parameter at redshift z, H0 is its present value, and Ω terms represent matter (m), radiation (r), dark energy (Λ), and curvature (k). This compact equation encodes a great deal of physics and connects directly to the observations discussed in observational evidence for dark matter and how we discovered dark energy.

n

n

Key distinction: dark matter clusters and enhances gravity; dark energy is smooth (on large scales) and drives cosmic acceleration.

n

nn

n

nn

nn

Observational Evidence for Dark Matter in the Universe

n

Multiple, independent lines of evidence indicate that most of the matter in the Universe is invisible and non-luminous. The consistency across very different scales and techniques makes the case for dark matter especially compelling.

nn

Galaxy Rotation Curves: Stars Orbit Too Fast

n

In spiral galaxies, stars and gas orbit the galactic center. Newtonian dynamics predicts that orbital speeds should decline with distance after most of the luminous mass is enclosed, much like planets in the Solar System. Instead, astronomers observe flat rotation curves: orbital speeds remain roughly constant far beyond the visible disk. This implies that mass continues to rise with radius, consistent with a large, extended dark matter halo surrounding the galaxy.

n

Rotation-curve studies using optical spectroscopy and 21-cm radio observations of neutral hydrogen consistently show this pattern across a wide range of galaxy sizes. Dwarf galaxies, which are especially dark-matter dominated, provide additional evidence: their internal motions require mass far exceeding the observed starlight and gas.

nn

Galaxy Clusters: The Case of nullMissingnull Mass

n

Galaxy clusters, the most massive bound structures in the Universe, offer three complementary mass estimates:

n

- n

- Galaxy motions: The velocities of member galaxies imply a deep gravitational well.

- Hot intracluster gas: X-ray observations reveal million-degree gas that is gravitationally confined, indicating a total mass far larger than the visible galaxies alone.

- Gravitational lensing: The deflection of background light traces cluster mass directly, independent of its composition.

n

n

n

n

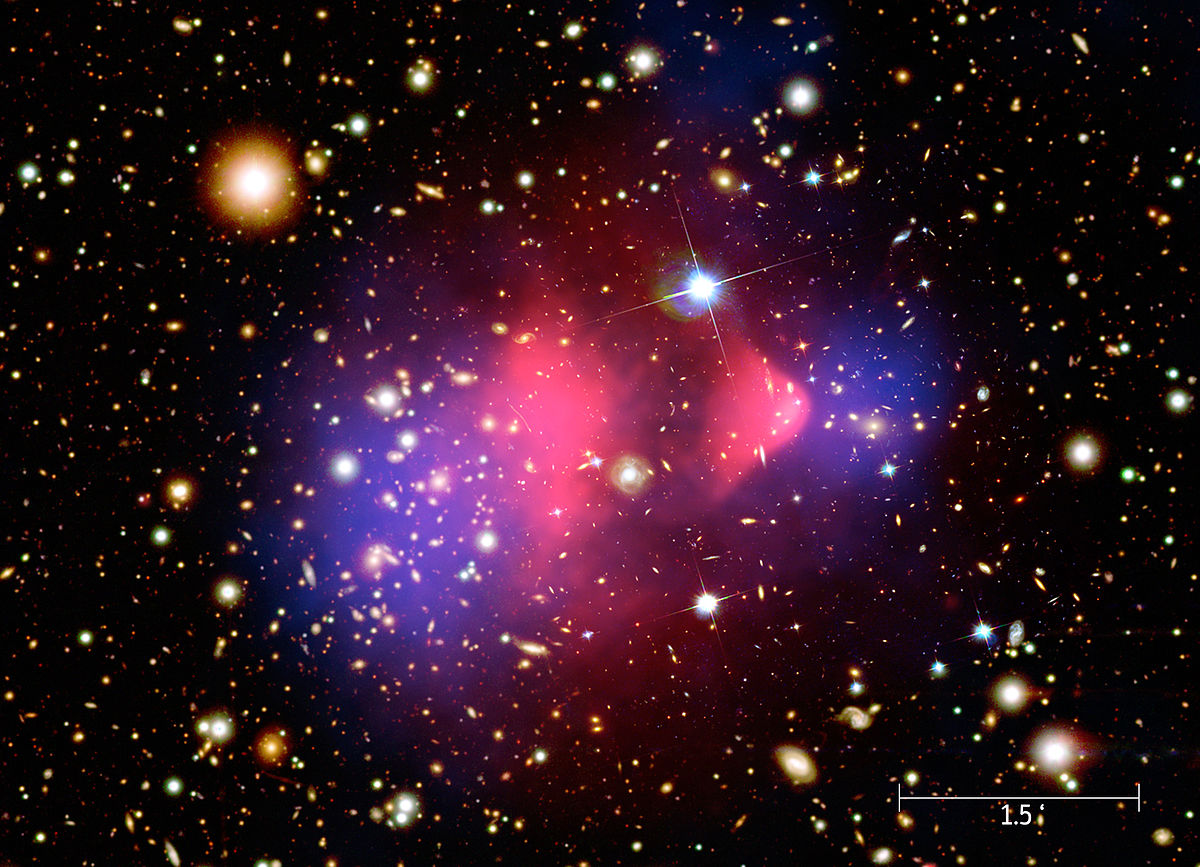

All three methods converge on the conclusion that the majority of a clusternulls mass is dark. A particularly vivid example is colliding clusters, such as the well-known nullBullet Cluster.null In such systems, the hot gas (which contains most of the ordinary matter) is separated from the bulk of the total mass inferred from lensing. This offsets the mass map (from lensing) from the baryonic map (from X-ray gas), strongly suggesting a collisionless mass component consistent with dark matter.

nn

n

nn

nn

n

These observations are tough to explain with modified gravity alone, because the mass peaks follow the galaxies (which pass through the collision) rather than the gas (which shocks and lags behind). We return to this and other alternatives in theoretical models and open problems.

nn

Gravitational Lensing Across Scales

n

Lensing comes in three principal flavors:

n

- n

- Strong lensing: Multiple images, arcs, or Einstein rings are produced when a massive object lies along the line of sight to a background source.

- Weak lensing: Small, coherent distortions in the shapes of many background galaxies, statistically analyzed to map mass distributions (cosmic shear).

- Microlensing: Time-variable brightening from compact masses passing in front of background stars, useful for detecting compact objects.

n

n

n

n

Weak lensing surveys reconstruct the total mass distribution independent of the light, confirming extensive dark matter halos around galaxies and clusters, and the filamentary network of the large-scale structure. This technique is central to nulltomographicnull studies discussed in how cosmologists measure invisible components.

nn

Cosmic Microwave Background (CMB) and Large-Scale Structure

n

The CMB, the relic radiation from the hot early Universe, contains subtle temperature and polarization anisotropies. Their statistical properties (e.g., the angular power spectrum) are sensitive to the composition of the Universe, including dark matter and ordinary matter. The heights and positions of the acoustic peaks in the CMB power spectrum indicate that non-baryonic dark matter was already dynamically important at the time of recombination.

n

Furthermore, numerical simulations using cold dark matter reproduce the observed nullpower spectrum of matter,null the current distribution of galaxies, and the way structures grew from tiny initial fluctuations. Observations of galaxy clustering and the Lyman-alpha forest (absorption features in quasar spectra) broadly align with a Universe where dark matter seeds structure formation.

nn

Nucleosynthesis Constraints: Not Enough Ordinary Matter

n

Big Bang nucleosynthesis (BBN) predicts the primordial abundances of light elements such as hydrogen, helium, and deuterium. These predictions depend sensitively on the density of baryonic matter. Measurements of primordial deuterium, along with CMB data, indicate that baryons account for only a fraction of the total matter needed to explain gravitational phenomena. Thus, the majority of matter must be non-baryonic, matching the dark matter picture.

nn

n

The evidence for dark matter spans galaxy scales to the entire observable Universe, tying together dynamics, lensing, the CMB, and the primordial element abundances.

n

nn

How We Discovered Cosmic Acceleration and Dark Energy

n

Dark energy emerged from an unexpected observational result: the Universenulls expansion is accelerating. The lines of evidence are independent and mutually reinforcing, building a robust case that a smooth component with negative pressure dominates the cosmic energy budget today.

n

Type Ia Supernovae: Standardizable Candles

n

Type Ia supernovae are thermonuclear explosions of white dwarfs in binary systems. They have remarkably uniform intrinsic luminosities, especially after empirical corrections based on their light-curve shapes and colors. By measuring their apparent brightness and redshift, astronomers can infer the expansion history of the Universe.

n

In the late 1990s, two independent teams used distant Type Ia supernovae to show that these objects were fainter than expected in a decelerating Universe. The simplest explanation: the expansion has been speeding up over the past few billion years. This discovery introduced nulldark energynull into mainstream cosmology and led to the modern ΛCDM model.

nn

n

nn

nn

Baryon Acoustic Oscillations: A Standard Ruler

n

Before recombination, baryons and photons were coupled in a hot plasma, supporting sound waves. When the Universe cooled enough for electrons and protons to combine (decoupling), these waves left an imprint: a preferred physical scale in the distribution of matter, known as the baryon acoustic oscillation (BAO) scale. Galaxy surveys measure this scale as a subtle bump in the correlation function and as wiggles in the power spectrum.

n

Because the physical BAO scale is well-calibrated by the CMB, observing it at different redshifts provides a nullstandard rulernull to trace the expansion history. The BAO measurements, combined with supernovae and the CMB, constrain the density of dark energy and test whether it behaves like a true cosmological constant.

nn

CMB Geometry and Late-Time Effects

n

The CMB does more than set early-Universe conditions. Its detailed anisotropies constrain the overall geometry and energy content. A spatially flat Universe (consistent with observations) with the observed matter density requires a dominant smooth component to account for the remaining energy budgetnullinterpreted as dark energy.

n

Moreover, the Integrated SachsnullWolfe effect (ISW) occurs when photons traverse time-evolving gravitational potentials in an accelerating Universe, leading to subtle correlations between the CMB and the distribution of large-scale structure at late times. These correlations support the presence of dark energy.

nn

Growth of Structure: A Complementary Probe

n

Dark energy not only accelerates expansion; it suppresses the growth of structures by diluting matter and altering the rate at which density fluctuations grow. Measurements of galaxy clustering, cosmic shear (weak lensing), and redshift-space distortions track this growth. The combined analysis confronts a self-consistent cosmic story: the same parameters that fit the expansion history also explain the timing and amplitude of structure formation.

nn

n

Cosmic acceleration is inferred from distances, standard rulers, CMB geometry, and the slowed growth of structurenulla cohesive, multi-probe picture.

n

nn

How Cosmologists Measure Invisible Components: Methods and Datasets

n

The strength of modern cosmology lies in cross-checks. Independent techniques target different systematic errors, and consistent results build confidence. Here are the core methods and why they matter, with references to earlier sections when relevant.

nn

Distance Indicators: From Parallax to Supernovae

n

- n

- Geometric parallax: Baseline measurements using Earthnulls orbit determine distances to nearby stars.

- Standard candles: Cepheid variables and the tip of the red-giant branch calibrate distances in nearby galaxies, tying into Type Ia supernovae.

- Type Ia supernovae: Standardizable candles reaching cosmological distances reveal the expansion history and cosmic acceleration (see dark energy evidence).

n

n

n

nn

Standard Rulers and Clustering

n

- n

- BAO: The baryon acoustic oscillation scale anchors distance measurements and Hubble parameter estimates at multiple redshifts.

- Redshift-space distortions: Galaxy peculiar velocities imprint anisotropies in the clustering pattern, constraining the growth rate of structure, sensitive to both dark matter and dark energy.

- Two-point statistics: Correlation functions and power spectra summarize clustering on different scales.

n

n

n

nn

Weak Lensing Tomography

n

Weak gravitational lensing measures tiny shape distortions of distant galaxies due to intervening mass. By splitting galaxies into redshift bins (tomography), one can map how lensing strength changes with distance, probing both the growth of structure and the geometry of the Universe. This technique complements the mass inferences from rotation curves and cluster dynamics and is central to modern dark energy surveys.

nn

CMB Anisotropies and Polarization

n

Temperature anisotropies map the early Universe, while polarization (especially E-mode patterns) refines parameter estimates. Together they yield precise constraints on the matter density, baryon density, and initial conditions. Cross-correlating the CMB with large-scale structure detects the ISW effect, linking the early and late Universe and informing cosmic acceleration.

nn

Galaxy Cluster Counts and Mass Calibration

n

Clusters form from high peaks in the matter density field. Their abundance as a function of mass and redshift is sensitive to the growth of structure and hence to dark energy. Multi-wavelength observations (X-ray, SunyaevnullZelnulldovich effect, optical richness, and lensing) provide complementary mass estimates. Accurate calibration across methods is crucial to avoid biases.

nn

Time Delays in Strong Lensing

n

When a variable source (like a quasar) is strongly lensed into multiple images, differences in path length and gravitational potential cause measurable time delays. Combined with lens models, these delays constrain the Hubble constant and the geometry of the Universe, providing a check that complements distance ladders and BAO.

nn

n

nn

nn

Cross-Correlation and Joint Analyses

n

Modern cosmology thrives on joint analyses that combine these probes. For example, combining weak lensing with galaxy clustering constrains galaxy bias and improves dark energy constraints; adding CMB data helps break degeneracies between matter density and dark energy equation-of-state parameters. The convergence of multiple independent probes is a hallmark of the evidence summarized in dark matter and dark energy sections.

nn

n

No single dataset settles the dark Universe. Itnulls the coherent pattern across supernovae, BAO, CMB, lensing, and clustering that gives us confidence.

n

nn

Theoretical Models: ΛCDM, Alternatives, and Open Problems

n

Observations alone donnullt tell us what dark matter and dark energy are. Theory aims to explain the data and predict new tests. The leading model is ΛCDM, but alternatives remain active research areas.

nn

ΛCDM: A Minimal, Empirically Successful Model

n

In ΛCDM, dark matter is cold (non-relativistic at early times) and collisionless; dark energy is a cosmological constant with equation of state w = null7 (pressure equals negative energy density). The model fits the CMB, large-scale structure, supernovae, and BAO with a small set of parameters, including the Hubble constant, matter density, baryon density, spectral index of initial fluctuations, and amplitude of primordial fluctuations.

n

Despite its success, ΛCDM raises deep questions:

n

- n

- Cosmological constant problem: Why is Λ so small compared to naive quantum vacuum energy estimates?

- Coincidence problem: Why are the densities of matter and dark energy of the same order today?

- Small-scale challenges: Issues such as the corenullcusp problem and too-big-to-fail in dwarf galaxies test the details of the dark matter paradigm, although baryonic physics may resolve many tensions.

n

n

n

nn

Particle Dark Matter Candidates

n

Candidate particles fall into broad categories, each with distinct signatures and constraints:

n

- n

- WIMPs (Weakly Interacting Massive Particles): Hypothetical particles that were thermally produced in the early Universe and froze out with the right relic density. Direct detection experiments search for rare WIMPnullnucleus scatters; indirect searches look for annihilation or decay products; colliders search for missing-energy signatures.

- Axions and axion-like particles: Extremely light bosons arising in solutions to the strong CP problem. Experiments use resonant cavities, nuclear magnetic resonance techniques, or astrophysical observations to look for axion signatures.

- Sterile neutrinos: Heavier neutrinos that donnullt participate in standard weak interactions. They could be warm dark matter candidates, with implications for small-scale structure.

- MACHOs (Massive Astrophysical Compact Halo Objects): Compact objects like black holes or faint stars. Microlensing surveys place strong constraints, indicating MACHOs cannullt account for most dark matter, though they may contribute a small fraction.

n

n

n

n

n

So far, no definitive laboratory detection has been made, which places increasingly tight constraints on the parameter space for some candidates. Astrophysical observations, especially on small scales, remain a powerful complementary testbed.

nn

Dark Energy Beyond Λ

n

If dark energy isnnullt a cosmological constant, its equation of state, w(z), could evolve over time. Scalar-field models (quintessence) or more exotic fields introduce dynamics that can be probed via precise measurements of distances and growth rates. Alternatively, gravity itself could deviate from general relativity on large scales, an idea tested by comparing geometry (distances) and growth (structure) measurements.

n

Testing these ideas requires accurate observations and careful control of systematics. The link between predictions and data is often encoded in phenomenological parameters such as the growth index or gravitational slip, which can be constrained by simultaneous fits to weak lensing, galaxy clustering, and redshift-space distortions (see methods).

nn

Modified Gravity Proposals

n

Modified Newtonian Dynamics (MOND) and relativistic extensions (e.g., TeVeS) can fit some galaxy rotation curves without invoking dark matter, especially on individual galactic scales. However, reproducing the full set of observationsnullsuch as cluster lensing maps, the CMB power spectrum, and the dynamics of merging clustersnullhas proven challenging for these models. Hybrids that include some dark matter along with modified gravity, or more complex dark sectors, are active areas of research.

nn

n

nn

nn

n

nn

nn

Open Problems and Tensions

n

- n

- Hubble tension: Some local measurements of the Hubble constant differ from values inferred from the CMB under ΛCDM. Whether this points to systematic errors or new physics remains under investigation.

- Amplitude of matter fluctuations: Certain weak lensing measurements of the parameter combinations involving σ8 and Ωm show mild tensions with CMB-based predictions, prompting studies of systematics and potential extensions to ΛCDM.

- Small-scale structure: The internal structure of dwarf galaxies and satellite counts test baryonic feedback models and possible warm dark matter scenarios.

n

n

n

nn

n

ΛCDM remains the simplest model consistent with most data, but open questions motivate new observations and theoretical innovation.

n

nn

From the Big Bang to Galaxies: How Dark Components Shape Structure

n

Dark matter scaffolded the cosmos; dark energy shaped its late-time fate. Understanding their roles clarifies why galaxies and clusters look the way they do and how the cosmic web formed.

nn

Seeds of Structure and Gravitational Growth

n

Quantum fluctuations during an inflationary epoch are believed to seed tiny density variations. As the Universe expands and cools, dark matter begins to clump under gravity. Baryons, once freed from radiation pressure at recombination, fall into the potential wells carved by dark matter halos. Over billions of years, this leads to a hierarchical assembly: small halos form first and merge into bigger ones.

n

Cold dark matter supports this bottom-up growth and reproduces the observed filamentary network seen in galaxy surveys and inferred from weak lensing (see tomography). The characteristic halo profiles and mass functions that arise in simulations align broadly with lensing and dynamical measurements, especially when baryonic processes are included.

nn

Reionization and the First Light

n

The first stars and galaxies emitted ultraviolet light that reionized hydrogen in the intergalactic medium. The timing and patchiness of this process depend on the formation of small halos and the feedback from early sources. Warm dark matter, if present, would suppress small-scale structure and delay early star formation, offering a way to constrain dark matter properties via high-redshift observations.

nn

Galaxy Formation and Baryonic Feedback

n

Dark matter sets the stage, but baryons perform the drama. Supernovae, stellar winds, and active galactic nuclei (AGN) inject energy and momentum into their surroundings, redistributing gas and sometimes flattening central density cusps into cores. Accounting for these processes is essential for comparing observations with the small-scale predictions of dark matter models and for addressing tensions like the corenullcusp problem.

nn

Clusters and the Cosmic Web

n

On the largest bound scales, galaxy clusters sit at the nodes of the cosmic web. Their abundance and internal structure record the growth of matter fluctuations and the expansion history. Observations of the intracluster medium (via X-ray and the SunyaevnullZelnulldovich effects) complement weak lensing mass maps to test cosmology. Meanwhile, filamentary structures connecting clusters, traced by galaxies and lensing, reflect the anisotropic growth shaped by dark matter dynamics.

nn

Late-Time Acceleration and Structure Suppression

n

As dark energy dominates, the expansion accelerates, stretching space more rapidly and slowing the growth of new structures. This redshifts galaxies out of each othernulls spheres of influence, making future mergers less likely and gradually freezing the large-scale pattern. Measuring this suppression with precision requires the combined probes discussed in methods, especially weak lensing and redshift-space distortions.

nn

n

Dark matter shaped the skeleton; dark energy decided how fast the flesh of galaxies and clusters could grow.

n

nn

Practical Implications for Amateur Observers and Science Enthusiasts

n

While the dark Universe may seem abstract, there are ways for enthusiasts to connect with the science, contribute to research, and appreciate the observations that support these ideas.

nn

Reading the Sky with Cosmology in Mind

n

- n

- Galaxy rotation curves: Amateur spectroscopy projects can measure emission-line velocities in nearby galaxies. While professional instruments reach far fainter objects, educational setups can reproduce the basic shape of rotation curves.

- Gravitational lenses: Public images from professional observatories often reveal arcs and Einstein rings. Learning to recognize these features deepens appreciation for lensing evidence (see lensing section).

- Galaxy clusters and filaments: Large public surveys offer maps of the cosmic web. Cross-referencing cluster catalogs with sky maps illustrates how mass congregates at nodes of structure.

n

n

n

nn

Citizen Science and Data Exploration

n

- n

- Galaxy classification: Morphology tagging improves studies of galaxy evolution within dark matter halos.

- Lensing discovery: Volunteers help identify candidate lenses in wide-field imaging, contributing to samples used in weak and strong lensing analyses.

- Supernova hunting: Transient surveys often enlist the public to flag candidate events, feeding into the standard-candle datasets described in dark energy evidence.

n

n

n

nn

Observing Guides with a Cosmological Twist

n

- n

- Look up cluster cores: When viewing a bright cluster galaxy through a telescope, consider the surrounding halo of dark matter that anchors the clusternulla tangible connection to cluster evidence.

- Follow transient alerts: Learning how supernova distances are standardized brings cosmic acceleration to life.

- Track survey releases: Public data releases often include beginner-friendly tutorials on cosmological measurements.

n

n

n

nn

n

Amateurs can connect to frontier cosmology through public data, citizen science, and a deeper interpretive lens on professional images.

n

nn

Current and Upcoming Missions Probing the Dark Universe

n

Major observatories and surveys have transformed our understanding of dark matter and dark energy. A combination of space-based missions and ground-based facilities maps the sky with unprecedented precision.

nn

Cosmic Microwave Background Missions

n

- n

- Past microwave observatories mapped temperature and polarization anisotropies with increasing precision, providing tight constraints on early-Universe parameters and the matter content.

- Ground-based CMB experiments continue to refine polarization measurements and small-scale anisotropies. These datasets anchor the early-Universe side of ΛCDM and calibrate nullstandard rulernull measurements used by other probes.

n

n

nn

Wide-Field Imaging and Weak Lensing Surveys

n

- n

- Space-based wide-field imagers conduct deep surveys optimized for weak lensing and galaxy clustering, providing high-resolution images over large areas of sky.

- Ground-based wide surveys image the sky repeatedly to map billions of galaxies, enabling weak lensing tomography, BAO measurements, and time-domain science, including supernova cosmology.

n

n

nn

Redshift Surveys and the Cosmic Web

n

- n

- Massive spectroscopic programs measure precise galaxy redshifts across large volumes, delivering BAO and redshift-space distortion constraints on the expansion history and growth of structure.

- Quasar and Lyman-nullb1 forest observations trace intergalactic gas, extending the reach of clustering measurements to higher redshifts.

n

n

nn

Cluster Observatories

n

- n

- X-ray telescopes map the hot intracluster medium, estimating masses and thermodynamic histories of clusters.

- Millimeter-wave instruments detect the SunyaevnullZelnulldovich effect, selecting clusters nearly independent of redshift and cross-calibrating masses with lensing.

n

n

nn

Why Multi-Probe is Essential

n

Each approach has its own systematics. For example, supernova cosmology must correct for dust and evolution; weak lensing must control shape measurement biases and photometric redshift errors; clustering analyses must account for galaxy bias. A multi-probe strategy reduces the impact of any one systematic and tests the consistency of ΛCDM or its alternatives across independent datasets. This interplay echoes the logic in how we measure invisible components.

nn

n

The dark Universe is being mapped by an ecosystem of observatories; the power comes from their synthesis, not any single measurement.

n

nn

Frequently Asked Questions

nn

Are dark matter and dark energy related, or completely separate?

n

As far as current evidence shows, dark matter and dark energy are phenomenologically distinct. Dark matter clusters gravitationally and behaves like a cold, pressureless fluid, influencing galaxy dynamics and structure formation. Dark energy appears smooth on large scales and has negative pressure, driving accelerated expansion. Some theoretical frameworks explore a unified nulldark sectornull or interactions between dark matter and dark energy, but no observational consensus supports a specific coupling at present. Distinguishing them relies on multi-probe measurements of geometry and growth, as described in methods and datasets.

nn

Could modified gravity explain observations without dark matter or dark energy?

n

Modifications to gravity can mimic some effects attributed to dark components, particularly on galaxy scales (e.g., fitting rotation curves). However, explaining the full suite of observationsnullCMB anisotropies, large-scale structure, lensing in clusters, supernova distances, BAO, and the growth historynullwith a single modified-gravity theory has proven difficult. Hybrid models that change gravity while retaining some form of dark matter or a late-time acceleration mechanism are being studied. Critical tests compare geometry (distances) and growth (structure formation) observables; if they disagree in a way inconsistent with general relativity, that would favor modified gravity. For now, ΛCDM remains the simplest model that fits the data across scales.

nn

Final Thoughts on Understanding Dark Matter and Dark Energy

n

Dark matter and dark energy are pillars of modern cosmology because they make disparate observations cohere. Rotation curves, cluster masses, and lensing maps point to invisible matter that gravitates like ordinary matter but doesnnullt shine. Supernova distances, BAO, and CMB geometry point to a smooth component that accelerates cosmic expansion. Together, they make sense of the large-scale structure we observe and the detailed imprints from the early Universe.

n

Despite this coherence, identifying the particle nature of dark matter and the physical origin of dark energy are among the deepest open questions in physics. Progress is likely to come from tightening constraints with multi-wavelength, multi-probe surveys; from laboratory experiments that continue to push sensitivity to candidate dark matter particles; and from new theoretical insights that connect cosmological observations to fundamental physics.

n

For enthusiasts and students of the cosmos, the best way to engage is to follow the data: public survey releases, cross-validated analyses, and mission updates. Consider exploring more articles in this series on topics such as gravitational lensing, large-scale structure, and cosmic distance ladders. If you enjoy deep dives like this, subscribe to our newsletter to get expert, accessible explanations of the latest results in cosmology delivered to your inbox.