Table of Contents

- What Is Numerical Aperture in Microscopy?

- How Numerical Aperture Governs Resolution and Depth of Field

- Illumination, Coherence, Wavelength, and Condenser NA

- Immersion Media and Refractive Index Mismatch

- Field of View, Magnification, and Sampling with NA

- Contrast Mechanisms and the Influence of NA

- Practical Trade-offs: Working Distance, Cover Glass, and Aberrations

- Selecting Objectives by Numerical Aperture for Common Tasks

- Calibration and Care: Verifying NA Performance and Alignment

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Final Thoughts on Choosing the Right Numerical Aperture

What Is Numerical Aperture in Microscopy?

Numerical aperture (NA) is the central optical parameter that determines how effectively a microscope objective (or condenser) gathers and focuses light. In simple terms, it expresses the light-collecting ability and angular acceptance of the lens. The higher the NA, the finer the details the objective can resolve, provided illumination and sampling are well matched.

The formal definition appears in nearly every optics text: NA = n · sin(θ), where n is the refractive index of the imaging medium at the lens front (air, water, glycerol, or immersion oil), and θ is half of the angular aperture of the objective—essentially the largest half-angle of light that the lens can accept from the specimen. Because sin(θ) cannot exceed 1, increasing NA beyond roughly 1.0 requires an immersion medium with n > 1. This is why oil-immersion objectives can reach NA values near or above 1.3, while typical air objectives have NA values around 0.65 or less.

Artist: QuodScripsiScripsi

Two distinct components of a brightfield microscope have numerical aperture specifications:

- Objective NA (e.g., 10×/0.25, 40×/0.65, 60×/1.40 oil) describes the collection cone of light from the specimen into the objective.

- Condenser NA (e.g., 0.9 dry, 1.25 oil) describes the illumination cone of light delivered to the specimen.

Matching these appropriately under Köhler illumination is crucial for achieving the full resolving power and contrast potential of the system. A mismatch—such as a high-NA objective paired with a low-NA condenser and a nearly closed aperture diaphragm—will restrict high spatial frequencies in the illumination and reduce effective resolution.

It is also common to see an NA range annotated on certain objectives, indicating that a correction collar or variable aperture can modify the effective numerical aperture. Adjustments like these can help optimize performance for different coverslip thicknesses or for specific contrast methods, topics we revisit in Practical Trade-offs.

How Numerical Aperture Governs Resolution and Depth of Field

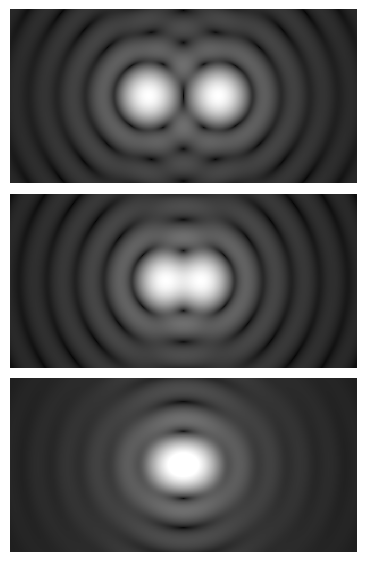

The connection between numerical aperture and resolution is one of the most important ideas in optical microscopy. Resolution describes the ability to distinguish two closely spaced points as separate features. For incoherent imaging (typical of brightfield microscopy with uniform illumination and fluorescence microscopy), a widely used measure is the Rayleigh criterion for lateral resolution:

Lateral resolution (Rayleigh, incoherent):

d ≈ 0.61 · λ / NA, where λ is the wavelength of light in the imaging medium.

This image uses a nonlinear color scale (specifically, the fourth root) in order to better show the minima and maxima.

Artist: Spencer Bliven

In practice, this means that increasing NA or using shorter wavelengths improves resolvable detail. For an objective at a given NA, switching from red to green or blue light will reduce the diffraction-limited spot size. Because the 0.61 factor pertains to the classical Rayleigh criterion, you may also encounter the Abbe spatial frequency cutoff formulation, which is consistent with the same physical relationships but expressed differently:

Abbe cutoff spatial frequency:

f_c ≈ 2 · NA / λ(for incoherent imaging), indicating the highest spatial frequency the system can transfer.

For coherent imaging (e.g., laser-illuminated systems with high spatial coherence), the cutoff frequency differs by a factor of two relative to the incoherent case, and system behavior changes accordingly. That distinction is discussed further in Illumination, Coherence, Wavelength, and Condenser NA.

Axial resolution and depth of field (DOF) also depend strongly on NA. As NA increases, the focal volume becomes thinner, and axial resolution improves. Under diffraction-limited assumptions and incoherent imaging, the axial resolution scales roughly with λ / NA² and the object-side depth of field also decreases approximately as 1 / NA². The exact coefficients and definitions vary depending on the contrast modality and criteria used, but two robust qualitative statements hold:

- Higher NA improves both lateral and axial resolution.

- Higher NA reduces depth of field, making precise focusing more critical.

This trade-off underlies many design decisions. For example, a high-NA oil-immersion objective may resolve sub-micron features in a thin specimen but demands meticulous focusing and precise coverslip control. A lower-NA air objective provides greater depth of field and working distance but cannot reveal the same high-frequency detail.

Another way to express the impact of NA is through the point spread function (PSF)—the characteristic diffraction-limited response of the microscope to a point source. As NA increases, the central lobe of the PSF narrows laterally and axially, boosting resolution but sharpening focus sensitivity. This is directly tied to the optical transfer function (OTF) and modulation transfer function (MTF), which quantify the spatial frequency response of the system and the contrast transferred at different spatial frequencies. A higher NA broadens the OTF support, increasing the range of spatial frequencies passed by the microscope.

Artist: Anaqreon (talk) (Uploads)

For practical imaging decisions, these principles converge on a few clear guidelines:

- When your goal is to distinguish the finest possible details, maximize NA and select shorter wavelengths compatible with your specimen and contrast method.

- When you need larger depth of field or more forgiving focus, choose a lower NA objective and adjust the condenser aperture to suit contrast requirements.

- Always consider the sampling capabilities of the camera or the acuity of the eye, since insufficient sampling can squander the resolution that high NA makes available.

Remember that the microscope is a system: objective NA, condenser NA, illumination coherence, wavelength selection, and sampling all collaborate to set the achievable resolution and contrast. Optimizing a single element while neglecting the others often yields disappointing results.

Illumination, Coherence, Wavelength, and Condenser NA

Illumination is not merely a brightness control; it determines how spatial frequencies are launched into the specimen and whether the objective can capture them. Three aspects are particularly relevant: coherence, wavelength, and the condenser numerical aperture.

Coherence and resolution criteria

Most routine transmitted-light brightfield systems operate under conditions that are effectively incoherent thanks to Köhler illumination. In such cases, the Rayleigh criterion d ≈ 0.61 · λ / NA and Abbe cutoff f_c ≈ 2 · NA / λ are suitable descriptors. In coherent imaging, common in laser-based modalities, interference effects change the transfer characteristics, and the cutoff frequency for coherent systems is different—effectively halving compared to the incoherent cutoff for otherwise similar parameters. This matters when comparing, for instance, a laser-illuminated confocal-like setup to a widefield fluorescence microscope with spatially and temporally incoherent excitation/detection arrangements.

Images donated as part of a GLAM collaboration with Carl Zeiss Microscopy – please contact Andy Mabbett for details.

Artist: ZEISS Microscopy from Germany

Practically, striving for spatially uniform and well-aligned illumination (Köhler) helps ensure that the condenser NA contributes appropriately to the optical transfer. You can read more about alignment strategies and verifications in Calibration and Care.

Wavelength selection

Resolution depends on wavelength. For a given NA, shorter wavelengths resolve finer features. In transmitted-light microscopy, green light often strikes a good balance between resolution and detector/eye sensitivity. In fluorescence microscopy, emission wavelengths are fixed by fluorophore properties, so resolution varies by channel. Choosing filters or light sources that match the intended contrast and spectral bands is a powerful way to optimize detail without changing objectives.

Condenser NA and aperture diaphragm

The condenser focuses light onto the specimen, and its NA determines the angular spread of illumination. Adjusting the condenser aperture diaphragm changes the effective illumination NA. Key effects include:

- Higher condenser NA increases contrast for fine details and supports the full spatial frequency bandwidth of a high-NA objective under incoherent conditions.

- Lower condenser NA can improve image contrast for low-contrast, coarse features by reducing glare and scatter, but it suppresses fine spatial frequencies and reduces resolution potential.

In brightfield, a common rule of thumb is to set the condenser aperture so that its image fills roughly two-thirds to three-quarters of the objective’s back focal plane. While not a strict requirement, this balance often yields good contrast without sacrificing too much resolution. For specialized contrast methods (phase contrast, DIC), the condenser configuration must follow the method’s prescribed setup so the modulation elements function as designed. Those relationships are explored in Contrast Mechanisms.

Immersion Media and Refractive Index Mismatch

The immersion medium at the objective front lens and between the condenser and specimen controls the refractive index n in the NA formula. Common values include approximately: air (~1.00), water (~1.33), glycerol (~1.47), and standard immersion oil (~1.515). These values vary slightly with temperature and wavelength, but the principle is consistent: a higher index allows a larger NA by permitting larger acceptance angles in the specimen medium.

Artist: Thebiologyprimer

Beyond enabling high NA, the immersion medium also influences aberrations, particularly spherical aberration arising from refractive index mismatches. Consider three practical issues:

- Coverslip thickness: Many objectives are corrected for a standard coverslip thickness (often around 0.17 mm, denoted as No. 1.5). Deviations introduce spherical aberrations that broaden the PSF and degrade resolution and contrast. Objectives with a correction collar allow compensation across a small range of thicknesses.

- Specimen mounting medium: The refractive index of the medium surrounding the specimen should be compatible with the objective’s design. A high-NA oil-immersion objective used on an air-mounted specimen across a thick glass substrate can suffer from mismatches that reduce effective NA and contrast.

- Condenser immersion: In transmitted-light systems, a high-NA condenser may be used with oil immersion to maximize the illumination NA for techniques that benefit from it. However, this is technique- and setup-dependent, and cleanliness becomes especially important to avoid scattering and flare.

Why does mismatch matter so much? The microscope objective is corrected under assumptions about the optical path. When those assumptions are violated—by coverslip thickness errors, tilt, or index differences—spherical aberration accumulates. The aberration expands the PSF and diminishes high spatial frequencies in the OTF, effectively acting like a loss of usable NA. Even if the objective is labeled with a high NA, practical resolution will be lower if mismatch is significant. Compensation via a correction collar, proper coverslip selection, and careful mounting reduces these errors and helps realize the rated performance.

When choosing between water, glycerol, or oil immersion, consider the specimen environment. For example, aqueous specimens are more naturally index-matched by water-immersion objectives, while fixed samples under standard coverslips typically favor oil immersion for maximum NA. Glycerol immersion sometimes offers a compromise in index while easing challenges posed by steep refractive index transitions.

Field of View, Magnification, and Sampling with NA

Numerical aperture alone does not guarantee resolved detail; the detection side—your camera or eye—must sample the image adequately. This is where magnification and field of view (FOV) enter the conversation. The fundamental idea is rooted in Nyquist sampling: to preserve information up to a certain spatial frequency, the sampling interval should be no larger than half the period of the highest frequency present.

Nyquist sampling and lateral resolution

Suppose a diffraction-limited system under incoherent imaging has a lateral resolution (Rayleigh) d ≈ 0.61 · λ / NA. To capture the spatial information in the final image without aliasing, the sampling interval in object space should be substantially smaller than d. A commonly cited guideline is to sample at or below half the resolution distance. Translated into an image-space criterion for a camera with pixel size p and objective magnification M, the object-space sampling is p / M. Therefore, p / M should be small enough—often taken as ≤ d / 2—to respect Nyquist for the highest transferred spatial frequencies.

Another practical articulation is to aim for an object-space sampling interval in the ballpark of one-third to one-half of the diffraction-limited spot size, balancing noise, detector sensitivity, and storage considerations. Oversampling may be acceptable (and sometimes desirable for processing workflows), but extreme oversampling increases data volume without adding new information, while undersampling wastes the optical resolution you gained by investing in a high-NA objective.

Eyepiece and field number considerations

For visual observation, the eyepiece field number (FN) and the objective magnification define the visible field of view: FOV ≈ FN / M (in object space, assuming matched optics). Higher magnification reduces FOV while improving the ability to see fine structures, provided NA is sufficient. The eye’s own sampling (photoreceptor spacing and visual acuity) and the observer’s focusing skill then determine how effectively that information is appreciated. While the eye lacks a precise pixel size comparison, the same principle holds: you cannot perceive fine detail that the optical system fails to transfer, and you cannot see what the eye cannot resolve. Choosing appropriate magnification to match NA ensures that the image scale is neither so small that details are lost to the eye nor so large that the view is uncomfortably narrow and dim.

Camera sensor size and parfocality

Digital imaging introduces additional choices related to sensor size, pixel size, and tube lens magnification (in infinity systems). Larger sensors can capture wider fields of view if the microscope’s optics provide a sufficiently large image circle. However, vignetting and off-axis aberrations must be considered, especially with very wide sensors and high-NA objectives. Ensuring parfocality between visual and camera paths aids workflow and lets you seamlessly switch between direct observation and imaging without refocusing, which is important when working with shallow depth of field at high NA.

For many systems, the constructive way to approach this is:

- Set the objective NA and illumination as desired for the detail you seek.

- Choose camera magnification and pixel size to sample at or below half the diffraction-limited resolution distance in object space.

- Confirm that the optical image circle accommodates your sensor without objectionable vignetting or off-axis blur, adjusting intermediate optics as needed.

These steps ensure that your resolution gains from NA are preserved through to the recorded image.

Contrast Mechanisms and the Influence of NA

Different contrast techniques in optical microscopy interact with numerical aperture in distinct ways. Understanding those interactions helps you tune the system for the best balance of resolution, contrast, and depth of field for your specimen and goals.

Brightfield

In brightfield, contrast arises from absorption and scattering differences in the specimen. High NA increases the transfer of fine spatial frequencies, enhancing the visibility of small structures if the specimen provides adequate contrast at those scales. However, excessive condenser NA may reduce global contrast in weakly absorbing samples by flooding the specimen with high-angle rays that reduce shadowing. Finding the optimal condenser aperture setting—often a fraction of the objective NA—helps balance sharpness and contrast. Köhler illumination is essential to ensure uniform illumination and to place the condenser aperture in proper conjugate planes.

Phase contrast

Phase contrast converts optical path length differences into intensity variations using phase rings in the objective and matching annuli in the condenser. The effective resolution is influenced by the objective NA, but the phase ring geometry and matching alignment also play critical roles by modulating which spatial frequencies are boosted or suppressed. Generally, higher NA improves the capture of fine phase variations, but the method’s intrinsic transfer characteristics may differ from brightfield. Correct alignment—centering the phase annulus and ring—ensures that the contrast mechanism operates as intended, and appropriate condenser aperture settings help maintain the desired trade-off between resolution and halo artifacts.

Differential Interference Contrast (DIC)

DIC uses shear and polarization optics to convert phase gradients into intensity contrast. Higher NA increases sensitivity to fine gradients because it supports higher spatial frequency content. DIC also benefits from precise control of shear bias and polarization states. While the underlying resolution capability follows the usual NA rules, the perceived sharpness and relief-like appearance also depend on the DIC prism settings and the orientation of specimen features relative to the shear direction. High-NA DIC can reveal subtle topographic-like information in transparent specimens when alignment and immersion match are optimized.

Fluorescence

In epifluorescence, excitation light is delivered through the objective and emitted fluorescence is collected by the same lens. NA strongly affects how many emitted photons are captured (collection efficiency) and what lateral and axial resolution are achievable. Since fluorescence is typically incoherent emission, the Rayleigh criterion applies, and shorter emission wavelengths (e.g., blue vs. red channels) yield finer lateral resolution at a given NA. High-NA objectives not only improve resolution but also increase signal by collecting light over a wider cone, which can be especially valuable for dim fluorophores. However, higher NA reduces depth of field and increases sensitivity to refractive index mismatch and coverslip thickness errors, so careful attention to immersion and mounting is important.

Darkfield and oblique illumination

Darkfield excludes the directly transmitted beam, allowing only scattered or diffracted light to contribute to image formation. Achieving good darkfield at high NA can be challenging because the condenser must deliver high-angle illumination that exceeds the objective’s collection cone for unscattered rays, while scattered light enters the objective. Thus, the condenser and objective NA relationship is critical. Small particles that scatter light weakly can stand out vividly in darkfield with a properly tuned condenser and objective pairing. As always, cleanliness and alignment are vital because stray light degrades the dark background.

Practical Trade-offs: Working Distance, Cover Glass, and Aberrations

Optical performance is always a balancing act, and numerical aperture sits at the center of multiple trade-offs. Three of the most prominent are working distance, coverslip requirements, and aberration sensitivity.

Working distance and NA

As NA increases, the front lens of the objective typically grows larger and closer to the specimen to accept high-angle rays. The result is a reduced working distance—the space between the objective front element and the focal plane. This constrains the kinds of specimens and mounting arrangements you can use. For instance, thick or uneven samples may be difficult to bring into focus without contacting the objective, which risks contamination or damage. In contrast, lower-NA objectives often have generous working distances, making them suitable for examining larger objects, microfabricated components, or specimens with pronounced topography.

Coverslip thickness and correction collars

Many high-NA objectives are corrected for a specific coverslip thickness. If your slides deviate from this standard or if you image through additional layers (adhesives, coatings, microfluidic channel roofs), spherical aberration may degrade image quality. Objectives with a correction collar provide a mechanical means to compensate within a limited thickness range. Proper use involves dialing the collar while observing a fine specimen until contrast and sharpness are maximized. Because axial resolution and depth of field are small at high NA, even minor misadjustments are noticeable.

Spherical aberration from refractive index mismatch

Index mismatch introduces path-dependent phase errors that grow with imaging depth and NA. Oil-immersion objectives used on specimens in aqueous environments face steep index transitions (oil → glass → water), and the mismatch worsens with increasing depth into the aqueous region. The perceived effect is a broadening of the PSF and a shift of optimal focus, reducing both resolution and contrast. Strategies to mitigate this include choosing immersion media and objectives matched to the specimen environment and minimizing unnecessary interfaces or thick intermediary layers.

Vibration, stability, and focusing sensitivity

A corollary of small depth of field is heightened sensitivity to vibration and focus drift. With high-NA objectives, tiny mechanical disturbances can blur fine detail. Even for casual observation, placing the microscope on a stable surface, minimizing touch-induced vibration, and avoiding drafts can materially improve crispness. For imaging, mechanical stability and thermal control improve repeatability, helping preserve the optical gains delivered by higher NA.

Selecting Objectives by Numerical Aperture for Common Tasks

Choosing the “right” NA depends on what you want to see, the specimen’s optical properties, and the constraints of your microscope. While it is impossible to prescribe a universal combination, the following examples illustrate how to match objectives and settings to typical goals. The descriptions are educational and avoid procedural steps; they focus on the underlying reasoning.

Surveying large structures and overviews

For quick overviews of relatively large features—such as printed circuit traces, microstructures on MEMS devices, plant tissue patterns, or crystal grains—low magnification and modest NA often suffice. An air objective in the range of 4×–10× with NA around 0.10–0.25 provides generous field of view and depth of field, making navigation easy. A condenser aperture set moderately low improves global contrast at the expense of some high-frequency detail, which is acceptable for reconnaissance imaging. Once you identify regions of interest, you can step up to higher NA for detailed study.

Intermediate detail on thin, transparent specimens

For transparent specimens such as thin sections of plant stems, diatoms, or microfabricated polymer films, a 20×–40× objective with NA ~0.40–0.65 balances detail and usability. Here, establishing Köhler illumination and matching the condenser NA to roughly two-thirds of the objective NA often yields crisp images with good contrast. If using phase contrast or DIC, align the optical elements carefully so the contrast enhancement boosts visibility of subtle features without sacrificing the spatial frequency transfer you obtain from the selected NA.

High-detail studies with immersion

When your goal is to resolve sub-micron features in thin, fixed samples under a coverslip, high-NA immersion objectives (60×–100×, NA ~1.20–1.40) become attractive. These provide finer lateral resolution and better axial sectioning compared to lower NA. However, they also demand careful attention to coverslip thickness, immersion medium cleanliness, and focus stability. Fluorescence imaging benefits not only from the resolution increase but also from higher photon collection efficiency within the large acceptance cone, which can be especially valuable for dim fluorophores. However, higher NA reduces depth of field and increases sensitivity to refractive index mismatch and coverslip thickness errors, so careful attention to immersion and mounting is important.

Artist: PaulT (Gunther Tschuch)

Specimens with topography or thick optics

Large working distance objectives with moderate NA can be a better fit for samples with uneven surfaces—such as assembled devices, rough crystals, or geological thin sections with variable topography. In these cases, the extra space reduces the risk of contact and contamination. Using slightly longer wavelengths (e.g., green) can compensate somewhat for the moderate NA by improving contrast in many transparent materials, though resolution will still be set fundamentally by NA.

Low-light considerations

High NA helps collect more light, which aids in low-light scenarios such as dim fluorescence channels. However, it also shrinks depth of field and can increase the sensitivity to background fluorescence or stray light near the focal plane. Balancing the condenser or excitation NA and employing clean, well-aligned optics makes a noticeable difference. Careful control of the illumination aperture often yields a cleaner image even if nominal resolution remains unchanged, simply by improving contrast transfer for the features of interest.

Calibration and Care: Verifying NA Performance and Alignment

Even the best optics cannot reach their potential without alignment and maintenance. Because numerical aperture translates directly into high-frequency information and collection efficiency, it is especially important to verify that the optical train is performing as expected. The points below summarize non-procedural, educational guidance to keep a system in good condition and to interpret what you see.

Köhler illumination and condenser alignment

Köhler illumination ensures that the field diaphragm and condenser aperture diaphragm occupy the correct conjugate planes, delivering even illumination and controllable illumination NA. A well-set condenser allows you to adjust the condenser aperture to support the chosen objective NA without introducing asymmetry or vignetting. If images appear unevenly bright across the field or if stopping down the condenser aperture causes asymmetric blur, there may be alignment issues that limit effective NA and contrast.

Focus and parfocality checks

Parfocal objectives should maintain focus when you switch magnification. If large focus shifts occur, or if the focal plane seems to wander unpredictably, verify that objectives are correctly seated and that the tube lens or camera path has not introduced unintended spacing changes. Wobble in the nosepiece or mechanical play can also reduce effective sharpness at high NA by making it difficult to place the focal plane consistently within the small depth of field.

Resolution targets and fine structures

To gauge whether your system approaches the expected resolution for a given NA and wavelength, examine high-contrast fine structures or test patterns with known feature spacings. Although real-world image quality depends on many factors (including specimen-specific contrast and scattering), the ability to distinguish progressively finer lines or periodic structures provides qualitative feedback. If unexpectedly coarse details are the limit, revisit illumination alignment, condenser settings, coverslip thickness, and immersion cleanliness before concluding that the optics are at fault.

Cleanliness and optical surfaces

High-NA imaging is sensitive to contamination on the coverslip, objective front lens, and condenser top lens. Dust, residue from immersion media, and fingerprints can scatter light, reduce contrast, and create flare that masks fine detail. Regularly inspecting and cleaning optical surfaces according to manufacturer guidance preserves contrast transfer and ensures that the lens attains its designed NA in practice. Avoiding unnecessary contact with the front lens, using proper lens paper and approved solvents where appropriate, and keeping immersion media fresh minimizes residue.

Mechanical stability

At high NA, even modest vibrations broaden the effective PSF during exposure. For visual work, a stable bench and a light touch yield noticeably crisper views. For imaging, shorter exposure times, careful cable management, and minimizing sources of mechanical disturbance help secure high-frequency information. These measures are not substitutes for optical alignment, but they ensure that your efforts in setting NA, wavelength, and illumination are not undermined by motion blur.

Frequently Asked Questions

Is resolution determined only by numerical aperture?

No. Numerical aperture is a primary determinant of diffraction-limited resolution, but actual image detail depends on a system of factors: illumination coherence and wavelength, the condenser’s NA, aberrations from refractive index mismatch or coverslip thickness, and the sampling of the camera or eye. If any of these elements limit the transfer of high spatial frequencies, you will not realize the full resolution potential implied by the objective’s NA. This is why optimizing illumination and condenser settings, maintaining proper immersion and index matching, and ensuring adequate sampling are all essential.

What happens if the condenser NA is lower than the objective NA?

When the condenser NA is set much lower than the objective NA in incoherent imaging, the illumination lacks high-angle rays, reducing the launch of fine spatial frequencies into the specimen. This can diminish contrast for small features and effectively limit resolution even though the objective itself could collect higher frequencies. In practice, moderately closing the condenser aperture can improve overall image aesthetics for certain specimens by increasing contrast and reducing glare, but closing it too far suppresses fine detail. The optimal setting depends on your contrast needs and the specimen, which is why many microscopists adjust the condenser aperture while watching how the image changes.

Final Thoughts on Choosing the Right Numerical Aperture

Numerical aperture links the physics of diffraction to the practical art of seeing fine detail. A higher NA narrows the point spread function, expands the optical transfer function, and collects more light—gifts that enable finer lateral and axial resolution and higher signal in low-light conditions. Yet those gifts come with obligations: smaller depth of field, shorter working distance, and heightened sensitivity to alignment, cleanliness, and refractive index mismatches. Mastery lies in understanding the interactions among NA, wavelength, illumination, condenser settings, and sampling.

When choosing objectives, allow the specimen and the imaging task to guide you. For broad surveys, a modest NA and generous field of view make exploration enjoyable and productive. For revealing the smallest structures, high-NA immersion brings you to the threshold of the diffraction limit, provided you respect coverslip thickness, immersion media, and stable alignment. Above all, remember that resolution is enabled by NA but realized only when the entire optical chain supports it.

If you found this deep dive into numerical aperture helpful, consider exploring related microscopy fundamentals, sharing this article with peers, and subscribing to our newsletter for future articles on illumination design, sampling strategies, and contrast optimization. Staying informed about the physics behind your microscope turns every session at the eyepieces—or the camera—into a more insightful experience.