Table of Contents

- What Is Numerical Aperture in Microscopy?

- How Numerical Aperture Governs Resolution: Abbe and Rayleigh

- Wavelength, Medium, and Immersion: Why n and λ Matter

- Magnification vs Resolution: Clearing Up Common Misconceptions

- Depth of Field, Depth of Focus, and NA Trade-offs

- Illumination, Coherence, and Contrast: Their Impact on Detail

- Digital Sampling and Nyquist Criteria for Microscope Cameras

- Practical Ways to Approach Diffraction-Limited Performance

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Final Thoughts on Choosing the Right Numerical Aperture

What Is Numerical Aperture in Microscopy?

Numerical aperture (NA) is the fundamental optical quantity that sets the limit on the detail a microscope objective can resolve. It quantifies the light-gathering and resolving power of an imaging lens in terms of geometry and refractive index, not simply magnification. Formally, numerical aperture is defined as:

NA = n · sin(θ)

Here, n is the refractive index of the medium between the specimen and the objective’s front lens (commonly air, water, glycerol, or immersion oil), and θ is the half-angle of the widest cone of light that can enter or exit the objective from the specimen plane.

Because NA combines both refractive index and collection angle, it simultaneously captures several key performance aspects:

- Resolution potential: Higher NA enables smaller resolvable features, as detailed in Abbe and Rayleigh criteria.

- Photon collection: All else equal, a higher NA collects more light emitted or scattered by the specimen, improving signal at the detector (useful for low-light imaging).

- Depth of field: Higher NA decreases the thickness of the in-focus region through the sample, discussed in depth of field trade-offs.

- Illumination coupling: In transmitted-light techniques, the condenser’s NA should closely match the objective’s NA to realize the objective’s full resolving power, a practical point expanded in illumination and coherence.

When reading an objective inscription such as “40×/0.65,” the first number is the magnification (40×), and the second is the NA (0.65). The NA often matters more for resolving power than the magnification, a theme we develop in Magnification vs Resolution.

Artist: PaulT (Gunther Tschuch)

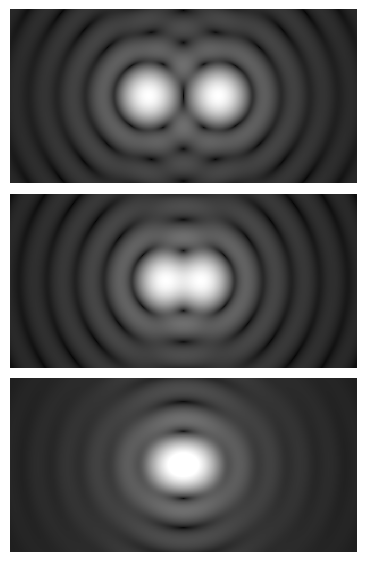

How Numerical Aperture Governs Resolution: Abbe and Rayleigh

Microscope resolution is constrained by diffraction. Even a perfect lens cannot form an arbitrarily sharp image of a point; instead, it produces a diffraction pattern known as an Airy disk. The characteristic diameter of the central bright spot sets a limit to resolving closely spaced details. Two foundational criteria quantify this limit for incoherent imaging (typical in brightfield under Köhler illumination and in fluorescence):

Artist: Spencer Bliven

- Abbe criterion: Lateral resolution d (minimum resolvable spacing) scales as

d ≈ λ / (2 · NA). - Rayleigh criterion: Lateral resolution d is commonly expressed as

d ≈ 0.61 · λ / NA.

Both formulas capture the same relationships: resolution gets better (smaller d) when the wavelength λ is shorter and the NA is higher. The difference is the numerical constant, reflecting slightly different definitions of when two points are considered “just resolved.” The Rayleigh criterion is often cited for practical microscopy because it corresponds to a recognizable intensity dip between two Airy patterns.

It is instructive to note that, for incoherent imaging, the optical transfer function (OTF) has a cutoff spatial frequency proportional to 2 · NA / λ. That means the highest spatial frequencies transferred by the system—and thus the finest detail—grow with NA and shrink with wavelength.

Axial resolution and sectioning

Resolution along the optical axis (axial resolution) also depends on NA and wavelength. Although several criteria exist, a widely used scaling relationship for widefield imaging is that axial resolution improves approximately as ~ λ · n / (NA²). In other words, increasing NA tightens the focal volume more strongly along the axial direction than in the lateral direction. This has important implications for 3D imaging and optical sectioning techniques (e.g., confocal microscopy), where a higher NA can yield thinner optical sections even before any computational processing.

Putting the numbers in context

Because the link between NA and resolution is so direct, the choice of objective NA is as consequential as the choice of magnification. Two practical consequences:

- Switching from an NA of 0.65 to 1.30 (with the same wavelength) halves the Rayleigh-limited lateral resolution d (because d is inversely proportional to NA).

- Switching from green to blue illumination (shorter wavelength) improves resolution, but only in proportion to the change in wavelength. NA changes often deliver larger gains than typical shifts in λ.

These scaling relationships appear repeatedly throughout this article and underlie the guidance in Final Thoughts on Choosing the Right Numerical Aperture.

Wavelength, Medium, and Immersion: Why n and λ Matter

Artist: Thebiologyprimer

Because NA = n · sin(θ), the refractive index n of the immersion medium directly affects NA. Immersion objectives take advantage of this by using media with refractive indices higher than air to capture steeper light cones (larger θ) without overwhelming aberrations at the interface.

Common immersion media and their role

- Air: n ≈ 1.00. Air objectives generally top out at NA values a little below ~0.95 because the maximum

sin(θ)is 1.0 and aberrations escalate near grazing angles. Air objectives are convenient and flexible, especially for dry specimens and quick surveys. - Water: n ≈ 1.33. Water immersion objectives are valuable for live or hydrated specimens where refractive index matching reduces spherical aberration through thicker aqueous media. They can achieve NA values comfortably above 1.0.

- Glycerol: n ≈ 1.47. Glycerol immersion can better match the refractive index of some mounting media or tissues than water, balancing aberration correction with higher NA potential.

- Oil: n ≈ 1.515 (typical microscope immersion oil). Oil immersion objectives can achieve the highest NAs commonly available in widefield microscopy, often around 1.3–1.4, enabling superior lateral and axial resolution.

When imaging through media that differ in refractive index from what the objective was designed for, spherical aberration increases, degrading resolution and contrast. This effect intensifies with specimen thickness and with increasing NA. Matching immersion media and cover glass specifications to the objective’s design mitigates these errors. While this article stays non-procedural, the concept underscores why specifications printed on an objective (e.g., cover glass thickness, immersion type) are not merely formalities; they set the conditions under which the advertised NA translates to real-world performance.

Wavelength selection and contrast mechanisms

Wavelength λ influences both resolution and contrast. Shorter wavelengths (e.g., blue light) improve theoretical resolution, as noted earlier. However, the choice of wavelength is often constrained by specimen properties and contrast mechanisms:

- Absorption and scattering: Biological and material samples absorb and scatter differently across the spectrum. Excessive absorption may elevate noise or photobleaching in fluorescence.

- Fluorescence: Excitation and emission bands are inherently tied to molecular properties. Emission wavelengths are typically longer than excitation wavelengths, which affects achievable resolution in the emission channel.

- Optical components: Lenses and coatings are optimized for particular wavelength ranges. Chromatic aberration control depends on the design, so high-NA objectives often specify recommended spectral bands.

Choosing the wavelength is therefore a balance between resolution, signal, and specimen integrity. The relationship between these factors and NA is explored from a systems perspective in Illumination, Coherence, and Contrast.

Magnification vs Resolution: Clearing Up Common Misconceptions

Magnification enlarges the image; resolution determines how much detail can be meaningfully enlarged. A microscope can produce an image that is very large but contains little additional detail if the optical resolution is the limiting factor. This mismatch leads to the two most common misconceptions in light microscopy.

Misconception 1: More magnification automatically means higher resolution

Increasing magnification without increasing NA does not improve optical resolution. If the system is diffraction-limited by an objective at NA = 0.65, pushing from 40× to 100× will produce a larger image of the same information. In practice, there is an upper bound commonly referred to as “useful magnification,” beyond which the image is just empty magnification—larger but not more detailed.

A widely cited guideline is that useful magnification scales with NA by a factor on the order of a few hundred to roughly a thousand (i.e., a few hundred to about a thousand times the NA). This rule of thumb is not a hard limit; it reflects the need to sample and display the diffraction-limited detail without stretching the same information across more pixels or screen area than necessary. The precise value depends on the detector’s pixel size, display, viewing conditions, and the observer’s visual acuity. The key point is that NA, not magnification alone, sets the fundamental resolution limit. This theme recurs in Digital Sampling and Nyquist.

Misconception 2: The best objective is always the highest magnification

Objectives at ultra-high magnification do not guarantee the highest resolution. A 100× air objective with modest NA can be out-resolved by a 60× oil objective with higher NA. Selecting objectives therefore requires attention to both magnification and NA—and to the specimen, immersion medium, and imaging modality. More on these trade-offs appears in Final Thoughts on Choosing the Right Numerical Aperture.

Why magnification still matters

Magnification remains essential because it sets the spatial sampling at the detector or the apparent image scale at the eye. For a camera, the sample-plane pixel size is the sensor pixel pitch divided by the total magnification. To faithfully capture the optical detail provided by the NA, the digital sampling must meet the Nyquist criterion, explained in Sampling and Nyquist. Thus, magnification and NA must be chosen together to translate the optical resolution into digital data without aliasing or wasted pixels.

Depth of Field, Depth of Focus, and NA Trade-offs

Resolution is not the only attribute affected by NA. The thickness of the region that appears sharp—depth of field (DOF) at the specimen and depth of focus at the image plane—is strongly tied to NA and wavelength.

Depth of field at the specimen

In widefield microscopy, a useful scaling is that DOF decreases approximately with the square of NA. A higher NA creates a tighter focus axially: fine for resolving thin features, but it reduces the thickness over which structures appear simultaneously crisp. While precise formulae include terms for defocus tolerance, refractive index, and wavelength, the essential trade-off is:

- High NA: Better lateral and axial resolution, shallower DOF.

- Lower NA: Lower resolution, but thicker specimen regions appear in focus at once.

This trade-off matters in thick specimens or when stacking focus planes is not practical. See Practical Ways to Approach Diffraction-Limited Performance for conceptual strategies that can mitigate DOF constraints without changing objectives.

Depth of focus at the image plane

Depth of focus is the tolerance for image-plane displacement (e.g., sensor or eyepiece plane) over which the image remains acceptably sharp. It also shrinks as NA increases. For digital imaging, depth of focus interacts with pixel size and demagnification optics, but the qualitative rule remains: higher NA demands tighter control of focus and mechanical stability.

Interplay with contrast mechanisms

Contrast-enhancing techniques such as phase contrast, differential interference contrast (DIC), and darkfield alter the imaging of defocused structures and edge detail. These techniques do not change the diffraction-limited resolution set by NA and wavelength, but they influence how features near the resolution limit become visible in practice by redistributing contrast. Details on illumination and coherence considerations appear in Illumination, Coherence, and Contrast.

Illumination, Coherence, and Contrast: Their Impact on Detail

Optical resolution and contrast are intertwined. Even if the NA and wavelength theoretically support a certain spatial frequency, the system must transfer it with sufficient contrast to be detectable. Illumination geometry, coherence, and condenser settings are central to whether the objective’s NA is fully utilized.

Condenser NA and the objective

In transmitted-light techniques (e.g., brightfield), the condenser forms the illumination cone impinging on the specimen. To realize the objective’s diffraction-limited resolution, the condenser’s effective NA should typically be comparable to the objective’s NA. If the condenser aperture diaphragm is stopped down too far, the illumination cone narrows, reducing the range of angles and, by extension, the system’s transfer of high spatial frequencies.

However, there is a trade-off: slightly reducing the condenser aperture can increase image contrast by limiting stray light and lowering the participation of high-angle rays that contribute weakly to image formation. This practice is often used to improve visibility of low-contrast specimens but at the cost of some resolution. The balance depends on specimen properties and the imaging goal. This subtlety connects to the common question addressed in Frequently Asked Questions.

Köhler illumination for uniform, high-quality imaging

Artist: ZEISS Microscopy from Germany

Köhler illumination is the standard approach for achieving spatially uniform and angle-controlled illumination across the field of view. By imaging the light source into the condenser aperture plane (not onto the specimen), Köhler separates control of illumination angle (via the condenser aperture diaphragm) from field uniformity (via the field diaphragm). Properly implemented, it supports the assumptions of incoherent or partially coherent illumination that underpin the Abbe/Rayleigh resolution relationships.

Coherence and the cutoff frequency

The degree of spatial coherence in the illumination alters the effective cutoff frequency of the optical transfer function. In simplified terms:

- Incoherent imaging (intensity-based; typical brightfield under Köhler, fluorescence): The OTF cutoff frequency scales with

2 · NA / λon the specimen side. This supports comparatively higher resolution for the same NA than coherent imaging. - Coherent imaging (e.g., laser illumination in some interference setups): The transfer function’s cutoff occurs at a lower spatial frequency, scaling with

NA / λ. As a result, coherent systems can exhibit stronger phase-sensitive contrast but a lower incoherent resolution limit for the same NA.

Many practical microscopes operate in regimes of partial coherence. The qualitative takeaway is that illumination geometry and coherence affect the details of the transfer function, contrast, and ultimate resolvability of fine structure. Still, the dominant scaling with NA and λ remains.

Contrast techniques and NA

Phase contrast and DIC transform phase variations into intensity differences, increasing the visibility of transparent features without changing diffraction-limited resolution. Darkfield uses oblique illumination to highlight scattered light, again without altering the fundamental resolution equations. These methods interact with NA through illumination angles and pupil modifications. For example, darkfield requires the condenser to illuminate at angles exceeding the objective’s acceptance cone so that only scattered light enters; adjusting NA on either side can make or break the effect.

Digital Sampling and Nyquist Criteria for Microscope Cameras

Digital imaging introduces another constraint beyond optical resolution: sampling. The camera must sample the diffraction-limited image finely enough to represent it without aliasing. The Nyquist–Shannon sampling theorem states that the sampling frequency must be at least twice the highest spatial frequency present in the image.

Relating optical cutoff to pixel size

Artist: Anaqreon

Suppose the optical system transfers spatial frequencies up to a cutoff f_c. To meet Nyquist, the specimen-plane pixel size p_s should satisfy p_s ≤ 1 / (2 f_c). For incoherent imaging, a common approximation is that f_c ≈ 2 · NA / λ. Combining these gives a practical rule of thumb:

p_s ≲ λ / (4 · NA)

This expression appears in equivalent forms depending on the contrast criterion (Rayleigh vs Abbe) and assumptions about the OTF. An often-cited guideline for widefield incoherent imaging is that the specimen-plane pixel size should be on the order of ~ 0.3 · λ / NA or smaller. The difference between 0.25 and 0.33 factors reflects different conventions and desired safety margins. The consistent message is that sampling must be sufficiently fine to capture the detail implied by NA and λ.

From sensor pixels to specimen pixels

Camera pixel size at the specimen is the sensor pixel pitch divided by the total magnification from the specimen to the sensor. For example, if the sensor has 6.5 µm pixels and the total magnification onto the camera is 60×, then p_s ≈ 6.5 µm / 60 ≈ 0.108 µm. Whether this meets Nyquist depends on the optical cutoff set by NA and λ. If the calculation is near the threshold, modest changes in magnification or the use of intermediate optics can align the sampling more closely with the optical limit.

Aliasing and “empty” resolution

If sampling is too coarse, high spatial frequencies fold into lower ones, creating aliasing artifacts and potentially misleading detail. If sampling is excessively fine compared to the optical limit, the image is oversampled: this does not add new information but may help with interpolation or noise reduction at a cost of larger data volumes. The sweet spot is determined by the NA, wavelength, and the application’s noise and speed requirements.

Signal, noise, and exposure

Higher NA can increase photon collection, which can improve signal-to-noise ratio per unit exposure. However, noise performance depends on detector characteristics (read noise, dark current, quantum efficiency) and on illumination constraints. While this article does not provide operational advice, it is important to recognize that the interplay of NA, sampling, and exposure determines what the instrument can practically reveal.

Practical Ways to Approach Diffraction-Limited Performance

Even without swapping objectives, several conceptual adjustments help a system approach its theoretical resolution for a given NA and wavelength. These are not procedural instructions but rather principles that explain why routine alignment and configuration matter so much in microscopy.

Match condenser NA to objective NA (transmitted light)

As discussed under Illumination and Contrast, achieving the full resolution of a high-NA objective requires an illumination cone with a comparable NA. If the condenser aperture is closed too far, the system effectively behaves as a lower-NA instrument in terms of transferred spatial frequencies. In practice, microscopists adjust condenser aperture to balance contrast and resolution depending on specimen properties, but the guiding principle remains: resolution is maximized when the condenser NA adequately fills the objective’s acceptance.

Control the wavelength

Where permissible, a shorter imaging wavelength reduces the diffraction-limited spot size. In fluorescence, the emission wavelength often dictates the resolution; filter sets and fluorophore choice therefore influence how the NA translates into measurable detail. In transmitted-light imaging, using a bluer band can improve resolution at a potential cost of scattering and contrast; choosing the band is a balance between visibility and diffraction limits, covered earlier in Wavelength and Immersion.

Manage refractive index mismatches

High NA amplifies the impact of refractive index mismatches between immersion medium, mounting medium, and specimen. Such mismatches cause spherical aberration that broadens the point spread function (PSF) and lowers contrast at high spatial frequencies. Matching immersion and cover glass specifications to the objective’s design helps maintain the PSF shape assumed by the Abbe/Rayleigh formulas. For thicker samples, objectives designed for those thicknesses or immersion media that better match refractive index can preserve resolution over depth.

Use angle-appropriate illumination in specialized modalities

Darkfield, oblique, and structured illumination techniques depend on carefully chosen illumination angles relative to the objective NA. For instance, in darkfield, the illuminating cone should exceed the objective’s NA so that only scattered light enters. The key is to maintain consistency between illumination geometry and the objective’s acceptance, underscoring the centrality of NA in both illumination and detection.

Coordinate NA with sampling

To make use of the optical resolution provided by a high-NA objective, sampling at the detector must satisfy the Nyquist criterion. If the sampling is too coarse, the high spatial frequencies enabled by the objective will not be captured. If sampling is overly fine relative to the optical cutoff, data volumes and noise per pixel may increase without adding information. The productive zone is dictated by NA and wavelength.

Accept trade-offs where needed

Not every imaging situation demands maximum resolution. Some applications benefit more from thicker depth of field, larger field of view, or higher speed than from pushing the diffraction limit. Selecting a lower-NA objective that delivers adequate resolution while boosting DOF or working distance can be the better choice. A few considerations:

- Thick specimens: Lower NA yields more of the structure in acceptable focus at once, reducing the need for focus stacking.

- Low-contrast samples: Slightly stopping down the condenser aperture can improve contrast even as it trims the highest transferred spatial frequencies.

- Speed and light budget: Lower NA may allow shorter exposures for the same field of view if other factors (illumination intensity, detector sensitivity) are fixed; conversely, higher NA can collect more light per unit solid angle, supporting lower illumination intensities for the same signal.

Frequently Asked Questions

Is 100× always higher resolution than 40×?

No. Resolution is governed primarily by numerical aperture and wavelength, not by magnification alone. A 40× objective with NA 0.95 can resolve finer details than a 100× objective with NA 0.70 at the same wavelength, even though the latter produces a larger image. Magnification must be matched to NA and detector sampling to avoid empty magnification, as discussed in Magnification vs Resolution and Digital Sampling.

Does closing the condenser aperture improve resolution?

Not generally. Closing the condenser aperture diaphragm increases image contrast by narrowing the illumination cone, but it also reduces the range of spatial frequencies the system can transfer, effectively limiting resolution. For maximum diffraction-limited resolution under transmitted light, the condenser NA should usually be similar to the objective NA. The best setting depends on the specimen and imaging goals, a balance addressed in Illumination, Coherence, and Contrast.

Final Thoughts on Choosing the Right Numerical Aperture

Numerical aperture is the cornerstone of optical performance in light microscopy. It defines the theoretical limit for lateral and axial resolution, shapes the depth of field, and influences light collection efficiency. Wavelength choice, immersion medium, and illumination geometry complete the picture by determining how the NA manifests as real, measurable detail.

When selecting or configuring an imaging setup, consider these takeaways:

- Prioritize NA for resolution: For a given wavelength, higher NA reduces the diffraction-limited spot size and improves both lateral and axial resolution.

- Balance NA with depth of field and working distance: Higher NA compresses DOF; in thick or uneven specimens, a moderate NA may better serve the imaging goal.

- Match illumination and detection: Condenser NA, coherence, and Köhler illumination all affect whether the objective’s NA translates into usable detail. Sampling at the detector must satisfy Nyquist relative to the optical cutoff.

- Choose wavelength and immersion thoughtfully: Shorter wavelengths and refractive-index matching help, but specimen properties and contrast mechanisms often dictate practical choices.

The most powerful microscope setups are designed as systems, not as collections of parts. By understanding how numerical aperture, wavelength, magnification, and sampling interact, you can predict performance and make informed decisions that suit your particular specimens and questions. For more educational deep dives on microscope fundamentals, subscribe to our newsletter so you never miss a weekly article—and explore related topics in our archive to continue building a strong, physics-informed intuition for imaging.

Artist: Ernst Leitz (Firm)