Table of Contents

n

- n

- What Is Numerical Aperture in Optical Microscopy?

- Diffraction, Airy Disks, and the Real Meaning of Resolution

- Magnification vs Resolution: How Much Is Enough?

- Illumination, Contrast, and the Role of Coherence

- Immersion Media, Cover Glass, and Spherical Aberration

- Digital Imaging: Pixel Size, Sampling, and Nyquist

- Choosing Objectives by NA, Magnification, and Working Distance

- Common Misconceptions About Magnification and Resolution

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Final Thoughts on Choosing the Right Numerical Aperture and Magnification

n

n

n

n

n

n

n

n

n

n

nn

What Is Numerical Aperture in Optical Microscopy?

n

Numerical aperture (NA) is among the most important specifications on a microscope objective and condenser. It captures, in a single number, how much light the lens can gather and how finely it can resolve detail. If you remember one thing about how microscopes form sharp images, remember this: higher NA generally means higher resolving power, stronger contrast transfer at fine spatial detail, and (for the objective) a shallower depth of field.

n

Formally, numerical aperture is defined as:

n

NA = n · sin(θ)n

where n is the refractive index of the medium immediately in front of the lens (for example, air ≈ 1.0, standard immersion oil ≈ 1.515 at room temperature, water ≈ 1.33) and θ is the half-angle of the widest cone of light that can enter (for an objective) or exit (for a condenser) the lens. The larger the acceptance cone, the more diffracted light the system collects from fine structures in the specimen.

n

Because NA multiplies the refractive index n, immersion objectives (oil, water, or glycerol) can reach larger NA values than air objectives. This directly benefits lateral resolution, as discussed in Diffraction, Airy Disks, and the Real Meaning of Resolution.

n

Two different NAs matter in transmitted-light microscopy:

n

- n

- Objective NA (NAobj) governs how finely the objective can resolve and how much light it can collect from the specimen.

- Condenser NA (NAcond) governs how steeply illumination rays strike the specimen. Filling the objective’s pupil with adequate illumination (NAcond comparable to NAobj in brightfield) helps reveal the highest spatial frequencies the objective can transmit.

n

n

n

When specifications list NA for an objective (for example, 40×/0.95 dry or 60×/1.40 oil), that decimal is the NA. It is not a unit; it’s a dimensionless measure of angular aperture in a refractive medium. While more familiar-to-beginners numbers like “40×” or “100×” describe magnification, the decimal (NA) is the better predictor of resolving power.

nn

n

nn Artist: QuodScripsiScripsin

n

nn

As you read the rest of this article, keep this mental map:

n

- n

- NA drives resolution and light-gathering.

- Magnification determines how large the image appears but does not, by itself, improve detail.

- Illumination and the condenser set the stage for the objective to reach its potential.

n

n

n

n

We will connect these variables—NA, diffraction, and magnification—in practical terms in the sections on Magnification vs Resolution and Digital Imaging and Sampling.

nn

Diffraction, Airy Disks, and the Real Meaning of Resolution

n

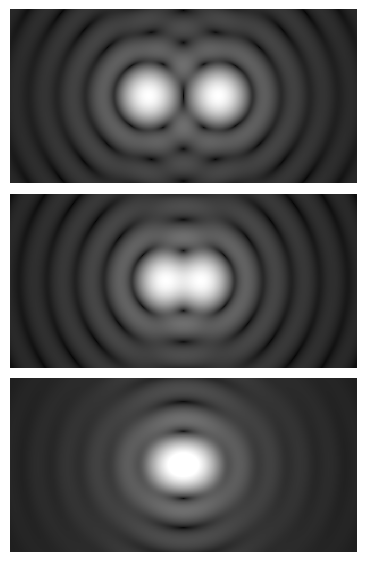

Even a perfect, aberration-free lens cannot form infinitely sharp points. Because light is a wave, any circular aperture (like an objective’s pupil) causes a point source to form a diffraction pattern: a bright central spot surrounded by rings. This pattern is called the Airy pattern. The radius of the central bright disk sets a hard limit on how close two points can be while remaining distinguishable.

nn

n

nn Artist: Anaqreonn

n

nn

Several equivalent ways exist to express the diffraction-limited resolution. Two widely used ones are:

n

- n

- Rayleigh criterion (two-point resolution): The minimum center-to-center spacing d between two point emitters that can be just resolved in incoherent imaging (typical brightfield fluorescence or white-light imaging) is approximately

d ≈ 0.61 · λ / NA, where λ is the wavelength in the medium (often approximated by the free-space wavelength for comparative purposes). - Abbe limit (periodic structures): The smallest resolvable period p of a line grid in incoherent widefield imaging is approximately

p ≈ λ / (2 · NA). This is consistent with the optical transfer function cutoff frequency for incoherent imaging,f_c ≈ 2 · NA / λ.

n

n

nn

n

nn Artist: Spencer Blivenn

n

nn

Both expressions scale inversely with NA and directly with wavelength: shorter wavelengths and larger numerical apertures resolve finer detail. In other words, improving resolution means either gathering diffracted light at larger angles (higher NA) or using shorter-wavelength illumination/detection when appropriate for your contrast mechanism.

n

It is also essential to appreciate the role of the condenser in transmitted-light techniques. For periodic objects, Abbe’s analysis shows that capturing diffracted orders depends on both illumination and collection angles. A well-adjusted condenser with NA comparable to the objective’s helps ensure that high-angle diffracted orders are generated and transmitted, maximizing effective resolution in brightfield. We return to illumination in Illumination, Contrast, and the Role of Coherence.

n

Resolution is not just about a single distance number. Two additional concepts help complete the picture:

n

- n

- Point spread function (PSF): The PSF is the 3D impulse response of the microscope to a point source. Laterally, the PSF shows the Airy pattern; axially, it is elongated along the optical axis. The PSF’s width determines how structures blur together and sets the fundamental limit on detail.

- Depth of field (DOF): As NA increases, the depth of field generally decreases. Put differently, a high-NA objective images a thinner axial slice of the specimen at once. This is why high-NA images look crisp at the focal plane but defocus quickly above and below.

n

n

n

These relationships have immediate, practical implications. For example, if you change from a 40×/0.65 air objective to a 60×/0.80 air objective, the magnification increases by 1.5×, but the lateral diffraction limit improves by a factor of 0.65/0.80 ≈ 0.81 (about a 19% improvement). If you move instead to a 60×/1.40 oil objective, the magnification is the same as the 60×/0.80, but the NA jump from 0.80 to 1.40 can nearly halve the diffraction-limited spot size. Magnification alone did nothing here; NA did the heavy lifting.

n

To summarize the core formulas that we will lean on throughout this article:

n

NA = n · sin(θ)nRayleigh two-point lateral resolution: d ≈ 0.61 · λ / NAnAbbe (periodic) lateral resolution: p ≈ λ / (2 · NA)nIncoherent OTF cutoff frequency: f_c ≈ 2 · NA / λn

These are first-order, diffraction-limited results. Real objectives also exhibit residual aberrations that can slightly degrade performance, especially off-axis or away from the specified cover glass thickness. We will discuss such practicalities in Immersion Media, Cover Glass, and Spherical Aberration.

nn

Magnification vs Resolution: How Much Is Enough?

n

“How much magnification do I need?” is a common question. The honest answer is: enough to sample the resolution your NA can provide—no more, no less. Overshooting magnification beyond what resolution supports yields a bigger, blurrier image (so-called empty magnification). Undershooting magnification, especially in digital imaging, squanders available detail because the sensor cannot sample the finest structure.

n

It helps to separate three ideas:

n

- n

- Optical resolution (set by NA and wavelength) tells you the smallest detail the system can form in principle, even with a perfect detector.

- Magnification is the linear size ratio between the specimen and the intermediate/image plane. It does not change the information content; it just changes the scale.

- Sampling (visual or digital) decides how finely the image is recorded or perceived. On a camera, sampling is set by effective pixel size at the specimen plane. To the eye, sampling is limited by eye resolution and exit pupil size, but the same principle holds: too little magnification under-samples the detail; too much does not add information.

n

n

n

n

From an information perspective, a balanced system makes the optical resolution and the sampling resolution match. For digital cameras, this is the Nyquist criterion, which we explore in detail in Digital Imaging: Pixel Size, Sampling, and Nyquist. For visual observation through eyepieces, a rough rule of thumb is that “useful magnification” tops out around 500× to 1000× per millimeter of objective entrance pupil diameter, which, in practice, scales with NA. A simpler educational guideline is that useful magnification is typically on the order of 500× to 1000× the NA for visual observation, but this is a heuristic to avoid glaring empty magnification at the eyepiece rather than a hard physical limit. The rigorous limit on detail always comes from NA and wavelength.

n

Instead of memorizing rules, ask: What NA do I have, and what smallest feature can it resolve at the wavelengths of interest? Then pick magnification so those features are adequately sampled by the eye or camera. This approach sidesteps confusion and puts the physics first.

n

Another practical angle concerns brightness. At a fixed NA, increasing magnification spreads the same light over a larger image, making it dimmer per unit area on the detector or retina. Conversely, increasing NA (at similar magnification) both improves resolution and gathers more light, often enabling shorter exposures or lower illumination intensities. The tug-of-war between magnification and brightness becomes evident in high-NA, short-working-distance objectives where precise focusing and stable illumination are crucial.

n

Finally, for contrast-based techniques (phase contrast, DIC, darkfield), the apparent fine detail depends on transfer of specific spatial frequencies and phase information. The objective NA still caps the highest resolvable frequency, but the contrast method shapes which frequencies are emphasized. This is another reason magnification alone is not a reliable predictor of how much you will see.

nn

Illumination, Contrast, and the Role of Coherence

n

Even the best high-NA objective cannot reach its theoretical resolution if the specimen is poorly illuminated. Transmitted light microscopy relies on the condenser to shape the illumination cone and control spatial coherence. The goals of good illumination are simple: even field brightness, control of contrast, and efficient generation and collection of high-angle diffracted light from fine features.

n

Two classic illumination schemes are often contrasted:

n

- n

- Critical illumination directly images the light source at the specimen plane. It can produce a bright image but tends to reproduce source structure (for example, filament texture or LED chip features) as unevenness in the field. While useful in certain setups, it is less forgiving than Köhler for general imaging.

- Köhler illumination forms a conjugate relationship that places the source at the condenser aperture and the field diaphragm at the specimen plane. This arrangement yields an evenly illuminated field and lets you control the effective illumination NA via the condenser aperture. Köhler is the standard recommendation for high-quality brightfield and contrast techniques because it produces spatially incoherent illumination at the specimen, supporting the incoherent imaging assumptions used in the resolution formulas.

n

n

nn

n

nn Artist: ZEISS Microscopyn

n

nn

Why does coherence matter? Incoherent illumination (typical in white-light brightfield and fluorescence) sums intensities of different paths, leading to an optical transfer function (OTF) with a cutoff frequency approximately 2 · NA / λ. Coherent illumination (for example, laser-based systems with spatial coherence at the specimen) instead sums amplitudes, producing a different OTF with a lower cutoff frequency approximately NA / λ. In practice, most transmitted-light brightfield is operated in the incoherent regime when using properly adjusted Köhler illumination and a condenser aperture that fills a substantial fraction of the objective pupil.

n

Several practical illumination controls interact with NA and resolution:

n

- n

- Condenser aperture diaphragm: Opening it increases illumination NA and generally improves resolution and contrast transfer of fine detail. Closing it reduces resolution, increases depth of field, and can boost edge contrast at the expense of high-frequency information.

- Field diaphragm: Adjusting the field diaphragm to just encompass the field of view improves contrast and reduces flare, especially important at high NA where stray light can wash out fine texture.

- Illumination color (wavelength): Shorter wavelengths improve diffraction-limited resolution but can reduce specimen transmission and may not be compatible with certain contrast methods. In fluorescence imaging, detection wavelength sets resolution in practice because the emitted light is what is imaged by the objective.

n

n

n

n

In reflected-light (episcopic) setups and fluorescence, the objective doubles as both condenser and imaging lens. The objective NA therefore simultaneously defines the illumination cone and the collection cone, often resulting in high-NA, high-resolution imaging. In these modalities the illumination coherence properties depend on the source and beam path (for example, arc lamps and LEDs are largely spatially incoherent at the sample when properly conditioned; lasers can be coherent). Regardless of modality, the unifying principle is the same: to approach the theoretical limits given earlier, the illumination must be configured to excite and capture high-angle diffracted light consistent with the objective’s NA. If illumination is too restrictive, the microscope underperforms.

n

A final illumination note: Resolution theory assumes no severe aberrations. Illumination that is grossly off-axis or poorly centered can induce asymmetries and reduce usable NA. Centering the condenser and ensuring uniform pupil fill are simple but powerful steps to achieve the performance predicted by diffraction theory.

nn

Immersion Media, Cover Glass, and Spherical Aberration

n

NA depends on the refractive index of the medium directly in front of the objective. This makes the choice of immersion medium and the control of optical path lengths at the specimen interface critical at high NA.

n

Immersion media and achievable NA

n

For air objectives, n ≈ 1.0, which caps the maximum possible NA near 1.0 because sin(θ) ≤ 1. In practice, high-quality air objectives top out below NA ≈ 1.0. Switch to a medium with higher refractive index, and the cap lifts:

n

- n

- Oil immersion objectives use oil with refractive index close to standard cover glass and typical immersion oils (approximately 1.515 at room temperature). This allows NA values significantly above 1.0, commonly around 1.3–1.4 in many systems.

- Water immersion objectives (n ≈ 1.33) enable high NA while better matching aqueous specimens, reducing refractive index mismatch at the sample interface and minimizing spherical aberration when imaging into water-based samples.

- Glycerol immersion (n ≈ 1.47) can strike a balance for thicker, more refractive samples and certain mounting media.

n

n

n

nn

n

nn Artist: Thebiologyprimern

n

nn

Which to choose? If you want maximum lateral resolution at the coverslip interface and your sample is well-matched to cover glass, oil immersion objectives can provide the largest NA. If you image into aqueous samples or slightly deeper beyond the coverslip, water immersion objectives often preserve resolution better by minimizing refractive index mismatch through the sample depth, even if the nominal NA is lower than an oil lens. The right choice depends on specimen refractive index, thickness, and how far into the specimen you focus.

n

Cover glass thickness and correction collars

n

High-NA objectives are designed to be used with a specific cover glass thickness and refractive index. A common standard cover glass thickness is approximately 0.17 mm (often marked as “1.5” or “1.5H” depending on tolerance), and many objectives are corrected for this value. Deviate substantially from the specified thickness or index, and spherical aberration increases, reducing resolution and contrast.

n

Some objectives include a correction collar, allowing you to tune the internal lens spacing to correct for small departures from the nominal coverslip thickness. When adjusted correctly, the collar can restore sharpness that would otherwise be lost. When adjusted incorrectly, it can degrade performance. The practical takeaway: if your objective has a collar, set it thoughtfully—preferably by optimizing image sharpness at the focal plane of interest or by following the manufacturer’s recommended adjustment method. If your objective does not have a collar, use the specified cover glass thickness and avoid thick mounting layers whenever possible.

n

Spherical aberration from refractive index mismatch

n

When light passes from one refractive index to another (for example, from cover glass to water), rays at different angles experience different path lengths, distorting the wavefront. The result is spherical aberration, which broadens the PSF, lowers peak intensity, and diminishes resolution. The severity grows with depth into a mismatched medium and with NA. This is why objectives optimized for oil at a coverslip often lose resolution when focusing deeper into aqueous samples, even if they have a high nominal NA.

n

Mitigation strategies include:

n

- n

- Choose immersion media that match the sample’s refractive environment when imaging thick or aqueous specimens (for example, water immersion for live aqueous samples).

- Use suitable cover glass thickness and minimize excess immersion layers between the coverslip and objective.

- For fixed, mounted samples, select mounting media with refractive index closer to the objective’s design conditions when feasible.

n

n

n

n

The central message echoes earlier points: a high NA on paper is only realized when the optical path in front of the objective matches the conditions for which the objective was corrected.

nn

Digital Imaging: Pixel Size, Sampling, and Nyquist

n

With digital cameras now standard on student, teaching, and research microscopes, understanding how pixel size and magnification interact with optical resolution is essential. Even with a diffraction-limited objective, a camera can under-sample fine detail if the effective pixel size at the specimen plane is too large. Conversely, a camera can over-sample detail (recording many pixels per diffraction-limited spot) without adding information, which may still be beneficial for processing but typically costs frame rate and storage.

n

Effective pixel size at the specimen

n

For a camera with physical pixel size pcam, the effective pixel size projected at the specimen plane is:

n

p_effective = p_cam / M_totaln

where Mtotal is the total magnification between the specimen and the camera sensor. In infinity-corrected systems, Mtotal is the product of the objective magnification and any intermediate optics (for example, a camera relay). In finite-conjugate systems, consult the system’s documentation to determine the net magnification to the camera.

n

As a simple illustration, if a camera has 6.5 µm pixels and it is used with a 60× objective without intermediate optics, then p_effective ≈ 6.5 µm / 60 ≈ 0.108 µm at the specimen plane. If the optical system’s diffraction limit at the relevant wavelength and NA is, say, 0.25 µm, then 0.108 µm per pixel provides a little more than two pixels per resolution element—close to Nyquist.

n

Nyquist sampling for microscopy

n

The Nyquist-Shannon sampling theorem says that to faithfully represent a band-limited signal, you must sample at least twice the highest spatial frequency present. In microscopy, the highest spatial frequency carried by an incoherent imaging system is approximately f_c ≈ 2 · NA / λ, corresponding to a smallest resolvable period of p_min ≈ λ / (2 · NA). Nyquist sampling then calls for a pixel pitch in the specimen plane of at most half that value:

n

p_effective ≤ (λ / (4 · NA))n

This inequality turns physics into design: once you know your imaging wavelength and NA, you can determine the effective pixel size target. For example, with λ = 550 nm and NA = 1.3, Nyquist suggests p_effective ≤ 550 nm / (4 · 1.3) ≈ 106 nm. Achieving this could mean using a 60× objective with a 6.5 µm pixel camera, or using a different combination that yields a similar effective pixel size.

n

In practice, different imaging modalities and processing steps may call for slightly different sampling densities. Some workflows prefer sampling around 2.3–3.0 pixels across the full width at half maximum (FWHM) of the PSF, which produces an effective sampling that often lies close to Nyquist for incoherent imaging. The key concept remains: sampling should be guided by the diffraction limit set by NA and wavelength, not by an arbitrary magnification aim.

n

Field of view and sensor size

n

As you change magnification to meet sampling criteria, your field of view on the sensor shrinks or grows. Larger sensors capture wider fields but demand higher-quality illumination uniformity and often more demanding optics. At high NA, maintaining even illumination and flatness across a large sensor field is challenging. If stitched mosaics are planned, try to balance sampling, field coverage, and optical vignetting control.

n

Empty magnification in the digital era

n

Empty magnification remains a risk when the camera already resolves what the optics can deliver. For instance, if p_effective is already far below λ / (4 · NA), increasing magnification further spreads photons over more pixels without revealing new optical detail. This can reduce signal-to-noise ratio per pixel for a given exposure, slow acquisition, and increase data volume. In such cases, consider whether your downstream analysis benefits from oversampling. If not, a lower magnification (or relay) that preserves Nyquist suffices and usually improves efficiency.

n

To connect these points back to system choice, see Choosing Objectives by NA, Magnification, and Working Distance, which applies the sampling guidance to the selection of objectives for different tasks.

nn

Choosing Objectives by NA, Magnification, and Working Distance

n

Choosing the “right” objective is not about picking the highest magnification you can afford. It is about fitting the numerical aperture, magnification, working distance, and correction class to your specimen, illumination, and detector. Here is a structured way to think about it.

n

Prioritize NA for resolution

n

If lateral resolution is your priority, NA matters more than magnification. Between a 40×/0.95 air lens and a 60×/0.80 air lens, the 40× lens can, in principle, resolve finer lateral detail despite lower magnification because 0.61 · λ / 0.95 < 0.61 · λ / 0.80. The higher-NA lens also tends to collect more light and can yield stronger contrast transfer of fine spatial frequencies. Choosing by NA first is a reliable rule when the goal is resolving power.

n

Balance magnification with sampling and field coverage

n

Once you have an NA in mind, select magnification that samples the diffraction-limited detail adequately on your camera (see Nyquist guidance) and provides the field coverage you need. If you are primarily observing visually, magnification should provide comfortable viewing without resorting to empty magnification. For cameras, a typical modern pixel size (for example, around a few micrometers) often pairs well with 40×–60× objectives to reach Nyquist at visible wavelengths and high NA. Larger pixels or longer wavelengths require more magnification for the same sampling; smaller pixels or shorter wavelengths require less.

n

Choose immersion medium for your specimen environment

n

If your specimen is under a standard cover glass and you work near the coverslip plane, oil immersion unlocks very high NA and best-in-class lateral resolution. If you image live cells in aqueous media or focus deeper into water-based specimens, water immersion objectives often preserve image quality with less spherical aberration. For thick, refractive samples where neither matches perfectly, glycerol immersion can provide a practical compromise. The decision should flow from the refractive properties of the sample and mounting medium, as explained in Immersion Media, Cover Glass, and Spherical Aberration.

n

Consider working distance and specimen geometry

n

Higher NA commonly means a larger front lens and a shorter working distance (the space between the front lens and the specimen at focus). For thick samples, micromanipulation, or protective covers, you may need a longer working distance objective even if that implies lower NA. Long working distance objectives are invaluable in industrial inspection and certain biological preparations because they provide clearance while preserving as much NA as feasible for the geometry.

n

Match the condenser

n

In brightfield transmitted-light imaging, the condenser NA should be chosen to support the objective’s performance. A general guideline is to use a condenser with NA comparable to the objective NA and set the aperture diaphragm to fill a substantial portion of the objective pupil. If the condenser NA is too small or the diaphragm is overly stopped down, high-angle diffracted orders are not generated or transmitted, and effective resolution falls below what the objective alone could deliver. This connection reinforces why illumination choices are as important as lens choices, as covered in Illumination, Contrast, and the Role of Coherence.

n

Correction class and cover glass sensitivity

n

Objectives come in various correction classes (for example, achromat, plan achromat, fluorite, apochromat), differing in how well they correct chromatic and spherical aberrations and field flatness. High-NA, high-correction objectives typically deliver superior image quality over more of the field and across broader wavelength ranges. If your specimens demand crisp edges across the entire camera sensor, a plan-corrected objective is helpful. If you image in multiple color channels, better chromatic correction helps maintain co-registration. Regardless of correction class, adhering to the specified cover glass thickness is crucial at high NA, or using the correction collar if provided, to maintain the theoretical resolution discussed in Diffraction and Resolution.

nn

n

nn Artist: PaulT (Gunther Tschuch)n

n

nn

Common Misconceptions About Magnification and Resolution

n

Misinformation thrives around microscopes, especially in social media and product marketing. Here are frequent misconceptions and the physically accurate clarifications.

n

- n

- Myth: Higher magnification always means higher resolution. Reality: Resolution is governed by NA and wavelength, not magnification. You can have a 100× objective with lower NA that resolves less than a 40× objective with higher NA. Magnification simply scales the image and must be matched to the sampling needs (Nyquist).

- Myth: Closing the condenser aperture improves resolution. Reality: Stopping down the condenser increases depth of field and can boost contrast of mid-frequency features, but it reduces illumination NA and normally lowers the system’s ability to transfer the highest spatial frequencies. For highest diffraction-limited resolution in brightfield, the condenser aperture should be sufficiently open to provide high illumination NA (Illumination and Coherence).

- Myth: Oil immersion always beats water immersion. Reality: Oil immersion often provides the largest NA at the coverslip interface and thus the best lateral resolution near the surface. But when focusing into aqueous specimens, refractive index mismatch at depth can introduce spherical aberration with oil, reducing effective resolution. Water immersion may outperform oil in such cases despite lower nominal NA (Immersion Media).

- Myth: More megapixels guarantee better microscope images. Reality: Pixel count is not the limiting factor if the optics under-sample or oversample relative to the diffraction limit. Pixel size and total magnification determine sampling. A balanced match to NA and wavelength matters more than raw megapixels (Digital Sampling).

- Myth: A correction collar can be set arbitrarily. Reality: An incorrectly set collar can harm resolution. Collars correct for specific cover glass thickness deviations. Optimize while observing fine detail at your imaging depth, or follow the manufacturer’s recommended method (Cover Glass and Aberration).

- Myth: Any bright LED or lamp will do. Reality: Illumination uniformity, stability, spectrum, and condenser alignment strongly impact contrast and the realization of diffraction-limited performance. Köhler illumination exists for a reason (Illumination and Coherence).

n

n

n

n

n

n

nn

Frequently Asked Questions

n

How does the condenser NA influence resolution in brightfield?

n

In transmitted-light brightfield, the condenser shapes the angular distribution of illumination at the specimen. Abbe’s analysis shows that to form an image of fine periodic structures, sufficiently high-angle diffracted orders must be generated by illumination and captured by the objective. A condenser with an aperture set to a high NA (comparable to the objective’s NA) provides these high-angle incident rays, enabling the objective to collect the resulting diffracted light. If the condenser NA is significantly lower than the objective NA or the aperture diaphragm is closed down too far, the highest spatial frequencies cannot be formed or transmitted effectively, and the system’s realized resolution falls below the objective’s potential. Opening the condenser aperture improves the transfer of fine detail, at the cost of reduced depth of field and sometimes increased glare if field control is poor. For general high-resolution brightfield, aim to fill a substantial fraction of the objective’s back aperture under Köhler illumination.

n

What sampling should I target for a camera to match my objective’s NA?

n

For incoherent widefield imaging, a practical target is to sample at or slightly finer than the Nyquist limit set by the diffraction cutoff. Using f_c ≈ 2 · NA / λ, Nyquist implies an effective pixel size at the specimen of approximately p_effective ≤ λ / (4 · NA). You can compute p_effective = p_cam / M_total from your camera pixel size and total magnification. Choose magnification (objective and any relay optics) to meet this target near your imaging wavelength. Sampling much coarser than this under-represents fine detail, while sampling much finer often yields diminishing returns in information content, though it may aid subsequent processing. Keep in mind that fluorescence and reflected-light imaging typically follow the same incoherent assumptions, whereas coherent systems differ in cutoff frequency. If in doubt, base your calculations on the dominant detection wavelength and objective NA, and verify empirically by imaging a resolution target or well-defined specimen feature.

nn

Final Thoughts on Choosing the Right Numerical Aperture and Magnification

n

Mastering light microscopy begins with understanding what really sets image detail. Numerical aperture defines how finely your system can resolve and how efficiently it collects light. Diffraction sets the fundamental size of the finest feature you can see. Magnification then scales that detail to your eye or camera. Illumination—especially the condenser in transmitted light—determines whether high-angle diffracted light is generated and captured. Immersion media and cover glass conditions decide whether the lens can realize its design performance without spherical aberration degrading the point spread function.

n

When you put these ideas together, practical decisions become straightforward:

n

- n

- Choose NA to meet your resolution needs at the wavelength you will use.

- Set magnification so your eye or camera samples that resolution adequately, avoiding empty magnification.

- Use appropriate illumination—preferably Köhler in brightfield—and match your condenser NA to the objective’s capability.

- Respect immersion and cover glass requirements to control spherical aberration, and consider water or glycerol immersion when imaging into aqueous or thick specimens.

- Align expectations around physics, not marketing numbers. The decimals after the objective name (NA) tell you more about image detail than the magnification label does.

n

n

n

n

n

n

If this overview helped clarify how numerical aperture, diffraction-limited resolution, and magnification interlock, explore related topics in our fundamentals series, from contrast mechanisms to illumination geometry. To keep learning with technically accurate, plain-language explanations like this, subscribe to our newsletter and get future articles delivered to your inbox.