Table of Contents

- What Are Jupiter’s Galilean Moons?

- Orbital Dynamics and the Laplace Resonance

- Surface Geology and Internal Structures of the Four Moons

- Habitability and Subsurface Oceans: Prospects and Cautions

- How to Observe the Galilean Moons: Practical Tips for Amateurs

- Discovery, Naming, and Cultural Impact

- Space Missions and Science Highlights

- Data and Numbers: A Handy Reference

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Final Thoughts on Exploring Jupiter’s Galilean Moons

What Are Jupiter’s Galilean Moons?

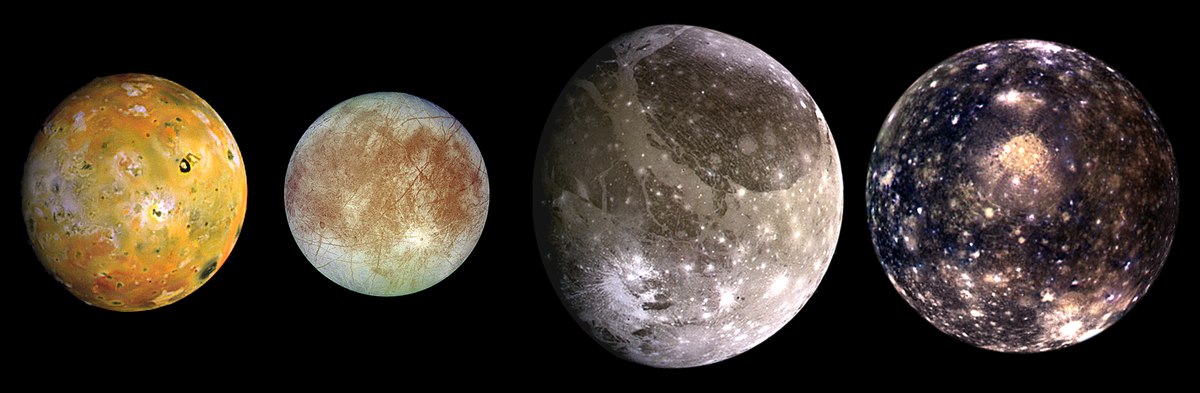

Jupiter’s four largest satellites—Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto—are known collectively as the Galilean moons. Observed by Galileo Galilei in January 1610, their discovery provided decisive evidence that not everything in the heavens revolves around Earth, lending crucial support to the heliocentric view. These worlds span a remarkable range of sizes, compositions, and geologic activity, making the Jovian system a miniature planetary laboratory. Three of the moons (Io, Europa, Ganymede) are locked in a gravitational dance called the Laplace resonance, while the fourth (Callisto) orbits farther out with a quieter geological history.

Why do the Galilean moons matter so much to modern planetary science? In brief:

- Scale and diversity: Ganymede is the largest moon in the Solar System, even bigger than Mercury. Io is the most volcanically active body known. Europa likely harbors a global subsurface ocean. Callisto preserves some of the Solar System’s oldest landscapes.

- Habitability potential: Evidence points to liquid water oceans beneath Europa’s and possibly Ganymede’s and Callisto’s ice crusts—prime targets in the search for habitable environments beyond Earth.

- Dynamical insights: Their orbits encode the story of tides, resonances, and long-term evolution in giant-planet systems.

This guide unpacks their orbital mechanics, geology, potential for life, and how to see them yourself. If you’re seeking a telescopic target that reveals new details with every look, the Galilean moons are ideal. For observing tips, jump to How to Observe the Galilean Moons. For mission highlights and what we’ve learned from spacecraft, see Space Missions and Science Highlights.

Orbital Dynamics and the Laplace Resonance

The Galilean moons occupy distinct orbits around Jupiter. Io, Europa, and Ganymede are bound in a 4:2:1 mean-motion resonance known as the Laplace resonance. This configuration shapes their internal heating, surface activity, and long-term evolution.

Distances and periods at a glance

Approximate orbital characteristics (semi-major axis and period):

- Io: ~421,700 km from Jupiter’s center; orbital period ~1.769 days.

- Europa: ~671,100 km; ~3.551 days.

- Ganymede: ~1,070,400 km; ~7.155 days.

- Callisto: ~1,882,700 km; ~16.689 days.

These values reflect nearly circular orbits, though small eccentricities matter hugely for tidal energy. The resonance keeps Io and Europa, and Europa and Ganymede, in integer period ratios (2:1 for each adjacent pair). The three-body relation can be written in terms of their mean longitudes (λ):

λ_Io − 3λ_Europa + 2λ_Ganymede ≈ constant

This relation keeps their orbital phasing in step. As a result, their gravitational tugs periodically reinforce orbital eccentricities. Tidal flexing of the moons’ interiors dissipates energy as heat, which is especially intense for Io and significant for Europa. The outcome is an active Io and a geologically youthful Europa, with Ganymede showing past and perhaps lingering internal dynamics. Callisto, not in the resonance, exhibits little tidal heating and a heavily cratered, ancient surface.

Tidal heating: the engine behind activity

Tidal heating is strongest where orbital eccentricity and proximity to Jupiter drive interior flexing. Io’s proximity to Jupiter combined with the resonance keeps its orbit slightly non-circular, continuously kneading its interior. Europa, farther out, still experiences substantial heating consistent with maintaining a global ocean beneath its ice shell. Ganymede’s heating is weaker but may have contributed to its complex history. Callisto, isolated from the resonance and residing in a weak tidal environment, appears to be the least processed internally.

One elegant aspect of the resonance is its self-maintaining nature. By exchanging angular momentum through gravitational interactions, Io, Europa, and Ganymede remain locked. Without significant external perturbations, this configuration persists for long timescales. That persistence is why Europa’s ocean is considered long-lived—a key point in the habitability discussion.

Surface Geology and Internal Structures of the Four Moons

Each Galilean moon offers a distinct planetary story. Their sizes, densities, and surface features chart a gradient from intense internal activity to ancient preservation. Below is a comparative snapshot, followed by deeper dives.

- Io (radius ~1,821.6 km; density ~3.53 g/cm³): Rocky, sulfurous, and intensely volcanic.

- Europa (radius ~1,560.8 km; density ~3.01 g/cm³): Ice-covered world with strong evidence for a global subsurface ocean.

- Ganymede (radius ~2,634.1 km; density ~1.94 g/cm³): The Solar System’s largest moon; differentiated interior and the only moon known with an intrinsic magnetic field.

- Callisto (radius ~2,410.3 km; density ~1.83 g/cm³): Dark, heavily cratered surface; a more primitive, less-differentiated interior.

Io: volcano world

Io’s surface is a patchwork of sulfurous plains, towering volcanic plumes, and lava lakes. Tidal heating fuels intense volcanism; hotspots have been documented across the globe. A standout feature is Loki Patera, a vast volcanic depression with episodic brightenings associated with resurfacing events. Deposits of sulfur and sulfur dioxide frost give Io vivid yellows, oranges, and whites.

Io’s tenuous atmosphere is dominated by sulfur dioxide (SO2), varying with volcanic activity and sunlight. Some gases escape into space, contributing to Jupiter’s magnetospheric environment. The moon’s robust volcanism constantly resurfaces the landscape, making impact craters rare.

Europa: the ocean beneath

Europa’s exterior is a shell of water ice. Its surface shows a mosaic of ridges, fractures, and relatively few craters, implying a geologically young surface. The shattered appearance—cross-cutting lineae, chaos terrains, and potential plume sources—suggests active or recent processes tied to ice-ocean interaction and tidal flexing.

Evidence from magnetic induction measurements indicates a conductive layer consistent with a global, salty ocean beneath the ice. The ice thickness is uncertain, with estimates ranging from a few kilometers to tens of kilometers, perhaps thickest globally but thinner in some regions. A tenuous oxygen atmosphere (molecular O2) arises from radiolysis: radiation breaks apart water molecules in the ice, releasing oxygen that accumulates as an exosphere.

Ganymede: the magnetic moon

Ganymede, larger than Mercury, is a world of contrasts. Its terrain includes older, dark, heavily cratered regions and somewhat younger, lighter grooved terrain indicative of tectonic reshaping. Internally, Ganymede is differentiated into a rocky core, an ice-rock mantle, and layers of ice and possibly liquid water. Observations reveal an intrinsic magnetic field, unique among moons. This field creates a miniature magnetosphere within Jupiter’s larger magnetic environment.

Like Europa, Ganymede likely harbors a deep subsurface ocean, possibly arranged in multiple stacked layers of ice and liquid water due to pressure-induced ice phases. Its atmosphere is extremely thin, with oxygen detected in the exosphere.

Callisto: an ancient archive

Callisto is the most cratered of the Galilean moons, preserving a surface record dating back billions of years. Enormous multi-ring structures, such as the Valhalla basin, encircle vast regions. The lack of extensive internal processing suggests Callisto never underwent full differentiation to the degree seen in Ganymede. However, magnetic induction hints at a subsurface conductive layer—possibly a salty ocean—though Callisto’s internal heat budget is lower and long-term ocean stability is a subject of study.

Callisto’s exosphere is exceptionally tenuous, with components like CO2 detected. The surface is darkened by radiation processing and dust, providing a stark counterpoint to the more active terrains of Io and Europa.

For a consolidated set of numbers, see Data and Numbers.

Habitability and Subsurface Oceans: Prospects and Cautions

The prospect that oceans exist beneath icy shells has transformed Europa and possibly Ganymede and Callisto into top targets in astrobiology. Yet, as exciting as the possibility of life is, researchers emphasize careful reasoning: an ocean does not guarantee habitability, and habitability does not guarantee life. Here’s what makes these environments compelling—and what we don’t yet know.

Europa’s ocean as a prime candidate

Europa’s ocean is considered the likeliest seat of habitability among the Galilean moons due to a compelling set of ingredients:

- Liquid water maintained by tidal heating.

- Energy sources from tidal flexing and possibly hydrothermal activity at the seafloor. If Europa has a rocky seafloor, water-rock interactions could deliver redox gradients similar to those exploited by Earth’s chemosynthetic life.

- Chemistry that may include oxidants created at the surface by radiation and delivered to the ocean via ice shell processes, plus potential salts and organics. The interplay of oxidants and reductants can sustain ecosystems.

Remote observations, including magnetometer data and surface geology, support the ocean model. Reports of transient water vapor plumes, based on Hubble Space Telescope observations, remain under discussion in the community. Confirming active plume sources would be a major development, as plumes could allow sampling of subsurface material without drilling.

Ganymede’s deep, layered ocean

Ganymede likely hosts a deep internal ocean sandwiched between high-pressure ice layers. While such a stratified ocean could be extensive, its contact with silicate rock at the seafloor may be limited or absent depending on the depth and phase layering. If there is no rock-ocean interface, the availability of certain chemical gradients could be reduced compared to Europa. Nonetheless, Ganymede’s intrinsic magnetic field and complex interior make it a central target for future exploration, particularly for understanding ocean structure and evolution.

Callisto’s potential ocean and energy limitations

Callisto may have a subsurface ocean indicated by magnetic induction signatures. However, with much lower tidal heating, the long-term stability and energy budget of any ocean are less clear. A colder interior and reduced geologic cycling could limit habitability, although interesting chemistry could still occur in isolated niches. Callisto’s ancient surface offers a complementary scientific case: studying primordial terrains and the effects of Jupiter’s environment on an old, relatively unprocessed world.

Radiation, chemistry, and the habitability equation

Jupiter’s intense radiation belts complicate the picture. Near Europa and Io, radiation doses at the surface are extreme. While radiation can produce oxidants useful to subsurface ecosystems, it also degrades organics and poses challenges for spacecraft and any prospective landers. Understanding how surface materials are cycled into the ocean—via cracks, subduction-like processes in ice, or brine migration—is central to assessing whether radiation chemistry supports or hinders habitability.

In sum, habitability requires sustained liquid water, energy, and the right chemistry. Europa leads on current evidence, but robust tests demand dedicated missions and in situ measurements, as outlined in Space Missions and Science Highlights.

How to Observe the Galilean Moons: Practical Tips for Amateurs

One of the joys of backyard astronomy is that you can see the Galilean moons with simple equipment. They look like tiny starlike points lined up near Jupiter, changing positions night to night—and even hour to hour—reflecting their orbital motion.

What you can use

- Unaided eye: Jupiter itself is bright, but the moons are lost in its glare. Even Ganymede, which can be as bright as magnitude ~4.6, is not practically separable by eye from Jupiter’s brilliance.

- Binoculars (7×50, 8×42, 10×50): These easily show Ganymede, Io, Europa, and Callisto as pinpoints on a steady night. Handheld viewing works, but a tripod helps.

- Small telescopes (60–100 mm refractors or 114–150 mm reflectors): Offer crisp views and reveal transits, shadows, and eclipses with patience. Larger apertures enhance resolution and enable more frequent detections of shadows crossing Jupiter’s disk.

How they appear and how far from Jupiter

The apparent separation of each moon from Jupiter varies. At a typical Earth–Jupiter distance, their maximum angular separations are roughly:

- Io: a couple of arcminutes from Jupiter at maximum elongation.

- Europa: around 3–4 arcminutes.

- Ganymede: about 5–6 arcminutes.

- Callisto: up to roughly 10 arcminutes when widest.

These separations make them quite tractable in binoculars and small telescopes. On some nights, all four line up on one side; on others, you’ll see two on each side. Their changing lineup is a vivid demonstration of orbital mechanics—see Orbital Dynamics and the Laplace Resonance for why.

Brightness and visibility

The moons vary around the following visual magnitudes:

- Ganymede: ~4.6

- Io: ~5.0

- Europa: ~5.3

- Callisto: ~5.6

These are bright enough for binocular detection under average skies but are easily swamped by Jupiter’s glare without optical aid.

Best times and simple planning

- When Jupiter is high: Aim for times when Jupiter is well above the horizon; you’ll get steadier seeing and less atmospheric distortion.

- During opposition season: Around opposition, Jupiter is nearest and brightest, and the moons are easiest to follow.

- Use an events calendar: Many sky almanacs and planetarium apps list moon transits, occultations, and eclipses. Watching a moon’s shadow transit across Jupiter is particularly striking.

Field notes format you can try

Keeping an observing log helps you notice patterns. You can adapt this simple layout:

Date/Time (UTC): 2025-01-12 03:30

Location: 40.7°N, 74.0°W

Instrument: 80 mm refractor, 120×

Seeing/Transparency: 3/5, 4/5

Notes: Io and Europa to the west, Ganymede and Callisto to the east.

Detected Europa’s shadow as a tiny round dot near Jupiter’s equator.

Tips for better views

- Stabilize optics: A stable mount or tripod reduces jitter and reveals finer detail.

- Use moderate magnification: 80–150× is often ideal for tracking shadows and transits without sacrificing contrast.

- Observe patiently: Jupiter’s turbulence changes moment to moment. Wait for fleeting steady intervals when details sharpen.

- Glare control: Slightly defocus Jupiter or use a neutral density filter to improve contrast for moon shadow transits.

Once you’ve watched a few transits and eclipses, circle back to Discovery, Naming, and Cultural Impact to appreciate how profoundly simple observations reshaped astronomy.

Discovery, Naming, and Cultural Impact

In January 1610, Galileo Galilei pointed a small refracting telescope at Jupiter and saw what he first took to be fixed stars near the planet. Over successive nights, he noticed these points changed position relative to Jupiter and to one another, leading him to identify them as satellites. This was groundbreaking: celestial bodies clearly orbited something other than Earth.

Almost simultaneously, Simon Marius observed the same moons and proposed classical names. Today we use Marius’s naming scheme—Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto—though the adoption took time. For centuries, astronomers often used Roman numerals (Jupiter I through IV), a convention still seen in scientific literature for clarity: Io (J I), Europa (J II), Ganymede (J III), and Callisto (J IV).

Their discovery had cultural reverberations beyond astronomy. It provided a powerful visual argument that not all celestial mechanics are geocentric, feeding into debates about science, philosophy, and theology. The moons also became an enduring target for telescopes of all sizes, a tradition that continues from backyard observers to flagship interplanetary missions.

Space Missions and Science Highlights

Spacecraft have transformed our understanding of the Galilean moons. Flybys and orbital missions have revealed volcanic eruptions, youthful icy surfaces, magnetic fields, and compelling evidence for subsurface oceans.

Pioneers and Voyagers

- Pioneer 10 and 11 (1973–1974): First spacecraft to explore the Jovian system, offering initial in situ measurements of Jupiter’s environment.

- Voyager 1 and 2 (1979 flybys): Returned striking images and discovered Io’s active volcanism. They mapped terrain types on Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto, setting the stage for future questions about interiors and geology.

Galileo orbiter: a revolution in the 1990s–2000s

Galileo arrived at Jupiter in 1995 and operated until 2003. With repeated targeted flybys, Galileo found strong evidence for subsurface oceans at Europa (and indications consistent with oceans at Ganymede and possibly Callisto) through magnetic induction signatures. It characterized Io’s volcanism and mapped intricate grooved terrain on Ganymede. The mission’s magnetometer detected Ganymede’s intrinsic magnetic field, reshaping our understanding of moon-scale dynamos.

Juno’s modern insights

Juno entered Jupiter’s polar orbit in 2016, primarily to study Jupiter’s interior, atmosphere, and magnetosphere. Over time, extended mission phases added close approaches to the Galilean moons:

- Ganymede flyby in June 2021 captured detailed imagery and measurements of the ionosphere and magnetosphere interaction.

- Europa flyby in September 2022 provided high-resolution images and additional constraints on surface geology and ice structure.

- Io flybys included close passes in late 2023 and early 2024, documenting volcanic activity and thermal hotspots with new detail.

Juno’s multi-instrument approach refined our view of how Jupiter’s environment influences the moons and vice versa, including particle populations, auroral footprints, and radiation processes.

Other contributors

- Cassini (Jupiter flyby in 2000): Acquired valuable imaging and spectroscopic data during its gravity assist.

- New Horizons (Jupiter flyby in 2007): Captured time-lapse movies of Io’s volcanic plumes and further constrained Jupiter’s magnetospheric dynamics.

Next up: Europa Clipper and JUICE

Two major missions target the Jovian system in the late 2020s and early 2030s:

- NASA’s Europa Clipper: Planned to conduct dozens of close flybys of Europa, focusing on ice shell structure, ocean properties, chemistry, and current activity. Its instrument suite is designed to map the surface at high resolution, probe the ice-ocean interface via radar, assess composition, and sample the near-moon environment for plume-related signatures if present. As of the time of planning, launch was scheduled for 2024, with arrival in the 2030 timeframe.

- ESA’s JUICE (Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer): Launched in 2023, JUICE is set to perform multiple flybys of Europa and Callisto and eventually orbit Ganymede. The mission aims to characterize ocean-bearing worlds, investigate habitability, and study magnetosphere-moon interactions.

The complementary objectives of Europa Clipper and JUICE promise a comprehensive portrait: Europa’s active and potentially habitable ocean, Ganymede’s magnetic and interior structure, and Callisto’s ancient record. With these missions, many of the open questions in Habitability and Subsurface Oceans can be addressed with direct measurements.

Data and Numbers: A Handy Reference

Here is a consolidated set of physical and orbital properties. Values are rounded and representative.

| Moon | Mean Radius (km) | Density (g/cm³) | Semi-major Axis (km) | Orbital Period (days) | Notable Traits |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Io | 1,821.6 | ~3.53 | ~421,700 | ~1.769 | Most volcanically active body; SO2 atmosphere |

| Europa | 1,560.8 | ~3.01 | ~671,100 | ~3.551 | Likely global subsurface ocean; youthful icy surface |

| Ganymede | 2,634.1 | ~1.94 | ~1,070,400 | ~7.155 | Largest moon; intrinsic magnetic field; grooved terrain |

| Callisto | 2,410.3 | ~1.83 | ~1,882,700 | ~16.689 | Heavily cratered; ancient surface; possible ocean |

For context: Jupiter’s equatorial radius is ~71,492 km, and the Galilean moons orbit within roughly 0.006 to 0.026 astronomical units of Jupiter. The Laplace resonance between Io, Europa, and Ganymede enforces period ratios of approximately 1:2:4.

If you plan to observe and record events, cross-reference these periods with local predictions of transits and eclipses as suggested in How to Observe the Galilean Moons.

Frequently Asked Questions

Are Europa’s plumes confirmed, and can spacecraft sample them?

Reports of transient water vapor plumes at Europa, based on Hubble Space Telescope observations, remain under active discussion. If plumes are present and persistent enough, flyby missions like Europa Clipper are designed to sample the near-moon environment for plume signatures using instruments tailored to measure particles and fields and to analyze potential plume material indirectly. Firm confirmation requires targeted observations, and results will depend on whether plumes are active during flybys.

Can I see the moons change position within a single night?

Yes. Because Io orbits in less than two days and Europa in just over three, you can often detect a subtle shift over an hour or two at the eyepiece—especially for Io. Watching across several hours can reveal a transit or an eclipse, and comparing your sketches or images to predictions from an almanac or app is a rewarding way to connect your observations with the orbital mechanics discussed in Orbital Dynamics and the Laplace Resonance.

Final Thoughts on Exploring Jupiter’s Galilean Moons

The Galilean moons are a cornerstone of planetary science because they span the spectrum from intense activity to ancient preservation. Io’s relentless volcanism showcases tidal heating at its peak. Europa’s likely global ocean and youthful surface keep it at the forefront of habitability studies. Ganymede, with its intrinsic magnetic field and complex interior, challenges our understanding of moon-scale differentiation and ocean structure. Callisto, largely untouched by major internal reworking, preserves an ancient record that complements the dynamism of its siblings.

From backyard binoculars to flagship spacecraft, these four worlds invite participation at every level. If you’re observing, the changing dance of the moons is an ever-renewing spectacle; if you’re reading mission updates, the coming years promise detailed maps, subsurface probing, and refined models of ocean chemistry and ice dynamics. To stay informed as new data arrive—and to dive deeper into observing guides, planetary science explainers, and mission briefings—consider subscribing to our newsletter. We’ll continue to cover the Jovian system with practical tips, curated background, and expert analysis you can trust.